Over the past few decades, rural Bangladesh has been undergoing profound transformations, both tangible and intangible. In a recent ethnographic study conducted by the BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD), we set out to explore these changes through the lived experiences and narratives of rural people. Drawing on fieldwork in ten villages across different districts, we sought to understand how villagers perceive and interpret the transformations that have reshaped their lives and communities.

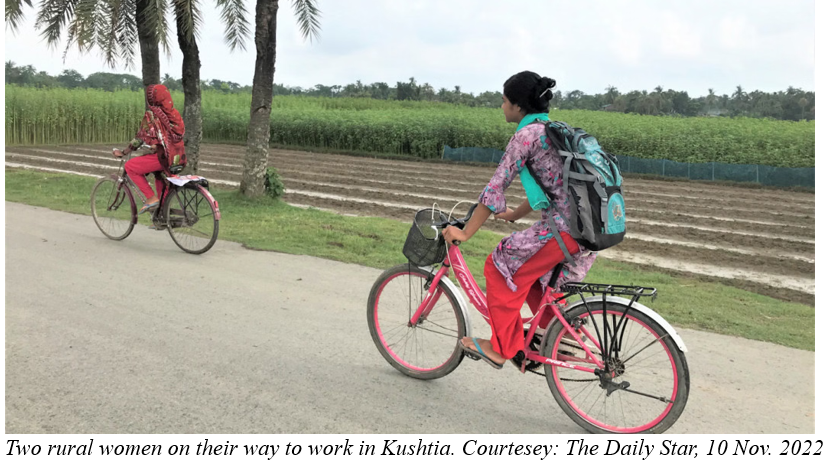

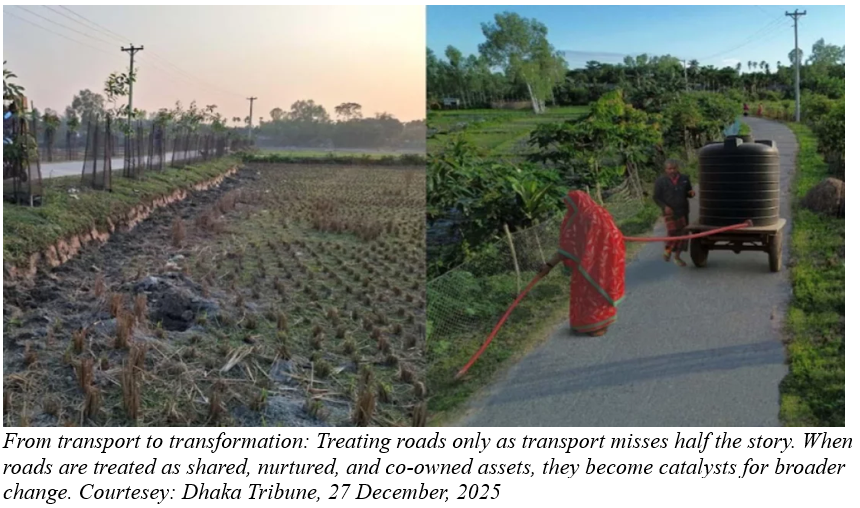

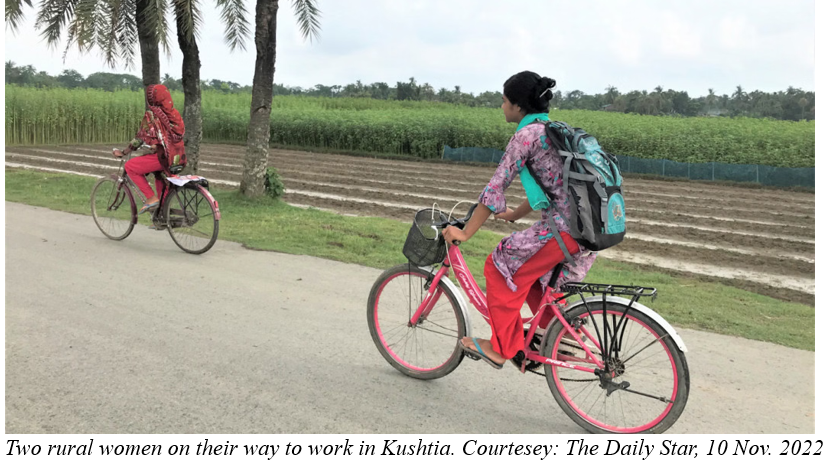

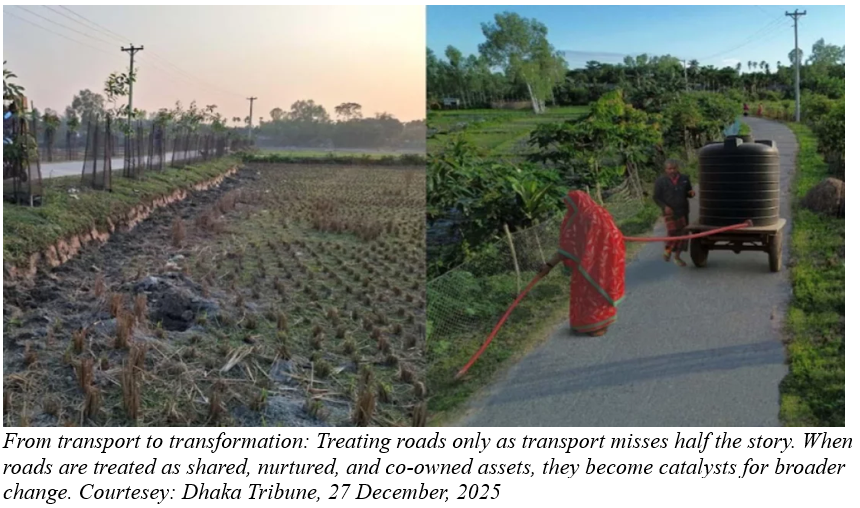

The visible changes are easy to identify: roads are paved, markets have expanded, digital connectivity has reached the most remote corners, and urban commodities now fill the village homes. Beneath these visible shifts lie subtler transformations, changes in behaviour, values, social relations, and aspirations that are harder to trace and are comparatively less discussed. It is within this interplay of the visible and the invisible that the story of the changing village unfolds.

When we asked villagers to describe the changes they had witnessed, most pointed to the familiar signs of infrastructural “development”: new schools, electricity, roads, mobile phones, and improved housing. These were the visible symbols of progress that aligned with the national political rhetoric of development, “Digital Bangladesh,” “Smart Bangladesh,” and “Bangladesh on the highway of development.” This dominant discourse shaped how people talked about their changing lives, primarily through a developmental lens. Yet, as our conversations deepened, it became clear that people’s everyday experiences of change are far more complex than these slogans suggest.

For some, development brought prosperity, opportunity, and comfort. For others, it meant displacement, loss of social ties, or erosion of traditional forms of community and livelihood. The villagers’ narratives remind us that “development” is a complex interaction of diverse factors that influence and reshape one another. To delve into this complexity, we listened to how people themselves made sense of change.

For some, development brought prosperity, opportunity, and comfort. For others, it meant displacement, loss of social ties, or erosion of traditional forms of community and livelihood. The villagers’ narratives remind us that “development” is a complex interaction of diverse factors that influence and reshape one another. To delve into this complexity, we listened to how people themselves made sense of change.

Compared to earlier times, as depicted in earlier rural studies, today’s villages stand as living proof of remarkable transformation. Mega projects, improved transportation, digitalisation, and increased urban connectivity have redefined the idea of what a “village” is. No longer isolated or self-contained, rural areas are now part of a continuous urban-rural spectrum. Yet, new questions emerge about identity, belonging, and the changing moral fabric of village life.

Our study approached these transformations through seven themes or dimensions: migration, culture, local institutions and social stratification, financial inclusion, environment and climate change, the built environment, and agriculture. These dimensions, while distinct, are interlinked; economic shifts influence family structures, migration reshapes social hierarchies, and technological changes affect livelihoods and cultural practices. Together, they create an entangled web of transformation that resists simple explanation.

One of the most striking changes we observed was in livelihoods and the everyday rhythms of life. Villagers today are busier than ever, engaged in diverse income-generating activities beyond agriculture, such as small-scale trade, factory work, transportation, or digital freelancing. Consequently, incomes have risen, but leisure has shrunk. The widespread adoption of mobile phones and the Internet has significantly altered leisure and entertainment. Traditional rural amusements—such as folk plays, village fairs, and music gatherings—have declined, replaced by urban-inspired forms of recreation and virtual engagements. This shift marks not only a change in entertainment but a deeper transformation in sociality itself: where entertainment in leisure was once communal, it has become increasingly individualised.

Urban influence now extends far beyond entertainment. Technology has reshaped agriculture, expanded markets, and linked local economies to the global capitalist order. The aspiration to become “modern” or “developed” has taken root in rural consciousness, visible in consumption patterns, housing styles, and even everyday language. Markets, both physical and virtual, have become the nexus where rural and urban worlds meet.

However, the march of development has also displaced many traditional livelihoods. The expansion of industrial production has marginalised local artisans—potters, weavers, and bamboo workers whose crafts once defined the village economy. Plastic has replaced biodegradable natural inputs like clay and jute. While these shifts signal convenience and efficiency, they also point to cultural loss and environmental degradation. Beneath the bright light of progress lies the shadow of exclusion. Those who fail to adapt to the new market realities often find themselves in urban slums, joining the growing ranks of informal labourers and rickshaw pullers.

The Green Revolution, too, transformed not just the economy but the culture of agriculture. Mechanisation has increased yields but reduced dependence on livestock, eroding the intimate human-animal relationships that once characterised agrarian life. Older farmers recall treating their cattle as family members; today, animals are raised as commodities. On the other hand, hybrid seeds, synthetic fertilisers, and pesticides have made agriculture capital-intensive and market-dependent, causing harm to soil health and broader biodiversity.

Simultaneously, the changing rural demography, the nature of land distribution, and the context of the labour market suggest a less communal atmosphere. The decline of mutual dependence among villagers has fostered a subtle but widespread individualism, where relationships are often driven by economic calculation rather than collectivebonding or responsibilities.

Parallel to these material changes, family structures and social relations have also undergone significant evolution. Economic mobility and migration, both internal and international, have encouraged the rise of nuclear families and weakened intergenerational ties. Grandparents, once central to family life, often find themselves sidelined, with their emotional and social roles often being ignored. Migration brings remittances and prosperity but also redefines intimacy, relationships, responsibility, care, and the overall social cost of migration.

Economic growth and exposure to global cultures have infused rural lifestyles with urban aspirations. Almost every village now mirrors aspects of city life—consumer goods, social media habits, and digital forms of expression. Yet this modernity is uneven and fraught. Beneath these developments lie anxieties about belonging, morality, and authenticity. While the digital turn has empowered many through access to information, it has also deepened the divide between those who can navigate technology and those left behind. It has also created new vulnerabilities, as online misinformation sometimes translates into real-world tensions and violence.

Rural people today live in two overlapping realities: one physical, grounded in their lived environment, and the other virtual, mediated by screens and networks. The intersection of these realities is where much of contemporary social life now unfolds.

To understand these transitions, one must look at change not as a linear progression from tradition to modernity, but as a process of continuous negotiation where gains and losses coexist, and where one form of advancement may give rise to new forms of vulnerability. We should also examine the intricate ways in which the social, economic, cultural, and political dimensions of life intertwine and reshape one another.

In this story of change, economic shifts influence cultural values, technological innovations redefine social interactions, environmental pressures alter livelihoods, and migration transforms kinship, local power structures, and communities, creating an entangled web of transformation that resists neat categorisation. In this entanglement lies the real texture of rural Bangladesh today, a society negotiating its position between past and future, between the collective and the individual, between the material and the moral.

Tanvir Shatil

Tanvir Shatil, Research Coordinator, BIGD, BRAC University. Tanvir joined BIGD as a Senior Research Associate. Prior to joining BRAC Institute of Governance and Development (BIGD), Tanvir was involved with different research projects of the Research and Evaluation Division (RED) of BRAC as a Staff Researcher. Shatil completed his BSS and MSS in Anthropology from Jahangirnagar University, Dhaka. His research interests lie in socio-economic and cultural transformation of peasant society and agricultural technologies, anthropological aspects of social psychology, public health, social power structure, and gender issues, among others.

For some, development brought prosperity, opportunity, and comfort. For others, it meant displacement, loss of social ties, or erosion of traditional forms of community and livelihood. The villagers’ narratives remind us that “development” is a complex interaction of diverse factors that influence and reshape one another. To delve into this complexity, we listened to how people themselves made sense of change.

For some, development brought prosperity, opportunity, and comfort. For others, it meant displacement, loss of social ties, or erosion of traditional forms of community and livelihood. The villagers’ narratives remind us that “development” is a complex interaction of diverse factors that influence and reshape one another. To delve into this complexity, we listened to how people themselves made sense of change.