Introduction

Bangladesh is a country in motion. The cranes rising over Dhaka, the bridges spanning mighty rivers, and the highways cutting through crowded towns all point to a nation determined to move forward. And yet, for all the fanfare, the reality on the ground often feels like being stuck in traffic: a frustrating mix of ambition colliding with dysfunction.

The truth is that our infrastructure story is not just about concrete and steel. It is about governance. It is about how decisions are made, whose interests are served, and whether institutions are strong enough to deliver on promises. Currently, the answer is painfully clear: we are trying to run before we have learned to walk.

At the heart of Bangladesh’s infrastructure struggle lies a problem that is both simple and deeply entrenched: weak governance. Institutions lack teeth, power is dispersed, and corruption often sets the rules. Projects begin with fanfare and end with ballooning costs, missed deadlines, and frustrated citizens.

At the heart of Bangladesh’s infrastructure struggle lies a problem that is both simple and deeply entrenched: weak governance. Institutions lack teeth, power is dispersed, and corruption often sets the rules. Projects begin with fanfare and end with ballooning costs, missed deadlines, and frustrated citizens.

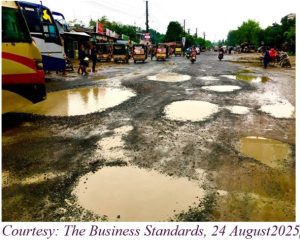

Consider the everyday experience. Roads are dug up, patched, and dug up again. Contractors complain about delayed payments. Ordinary people suffer through endless traffic jams. Scarce resources, outdated bureaucracies, and political interference continue to cripple local governments, which should have the authority to manage projects closest to the people.

This case is not an isolated incident. This is systemic. Ministries and agencies overlap, duplicating jobs and wasting resources, without a framework. The Ministry of Road Transport manages highways, the Ministry of Housing structures, and another department powers plants. The result? Mismatched strategies without a vision. The governance system operates in silos, lacking a clear strategy.

Plans on paper, chaos on the ground

Bangladesh has no shortage of plans—Five-Year Plans, Vision 2021, Perspective Plans, sectoral roadmaps. Each of them lays out ambitious goals for connectivity, transport, and communications. Glossy brochures and lofty rhetoric often accompany promises of bridges, tunnels, expressways, and railways.

But planning on paper is one thing; turning it into reality is another. Without coordination, one project undermines another. Without clarity, money is wasted on misaligned priorities. The political temptation to announce “mega projects” trumps the tedious and unglamorous work of maintenance, coordination, and accountability.

The irony is cruel. On the one hand, Bangladesh dreams of becoming a regional hub, linking South and Southeast Asia. On the other, potholes swallow vehicles on rural roads, ferries sink in neglected rivers, and half-finished projects sit like abandoned monuments to mismanagement.

The capacity syndrome

We frequently think of infrastructure in terms of money. Bangladesh faces financial and capability issues. Call it “capacity syndrome.” Infrastructure projects in Bangladesh face several challenges, including resource incapacity, productivity incapacity, regulatory incapacity, debt incapacity, procurement incapacity, risk management incompetence, institutional weakness, human deficiency, and technology gaps. Infrastructure projects receive underfunding despite spending 6-9 per cent of GDP on them, which poses threats to debt sustainability. Outdated tools, poor project management, and a lack of skilled labour hinder productivity.

Regulatory incapacity is exacerbated by corruption, favouritism, and bid-rigging, causing delays and cost overruns. Debt incapacity is exacerbated by growing borrowing, and procurement incapacity is plagued by delays, opacity, and corruption. Bangladesh’s climate vulnerability reveals risk management incompetence, as disaster-resilient infrastructure is scarce. Institutional weakness is further exacerbated by unclear roles, conflicting policies, and bureaucracy. Human deficiency is also evident, with scarce engineers, planners, and technicians. Technology gaps are also a concern, with underfunded R&D and inadequate technological transfer. Simply put, Bangladesh lacks the institutions, expertise, and safeguards to use money.

The maintenance mirage

Bangladesh has a bad habit: we love to build, but we hate to maintain. A new bridge is cause for celebration; a ribbon-cutting ceremony is broadcast on television. But once built, it is often left to crumble.

Budgets for maintenance are meagre. Skilled repair crews are scarce. Asset management is weak. Roads develop cracks within years. Rural waterways, once vital, become clogged and unusable. Energy grids falter due to poor upkeep.

This obsession with new construction over long-term care is not just financially reckless; it is dangerous. Without maintenance, infrastructure becomes a liability, not an asset.

Behind all the talk of capacity and governance lies a very real human story. A worker labours on a construction site using antiquated equipment. The small trader, whose goods languish in traffic due to unending delays, is another real-life example. The schoolgirl misses class because her village road becomes impassable after the monsoon.

These are not abstract governance failures. They are daily injustices that keep people poor, frustrate ambition, and erode trust in government.

What Must Change

Bangladesh cannot allow infrastructure to continue being the primary obstacle in its development journey. The path forward requires not just more money, but smarter governance.

First, a unified vision or a single, coherent strategy for infrastructure is essential—one that aligns ministries, avoids duplication, and sets clear priorities. Piecemeal plans will only produce piecemeal results.

Second, we need stronger institutions. Agencies must be streamlined, responsibilities clarified, and accountability enforced. Overlapping mandates must provide a way to coordinated action.

Third are the twin pillars of governance—transparency and accountability. Public procurement must be cleaned up. Citizens should know where money is going, contracts should be awarded fairly, and corruption must be punished, not tolerated.

Fourth, we need to invest in our people. Training engineers, planners, and skilled workers is as important as pouring concrete. Retaining talent with fair pay and professional growth is vital.

The fifth aspect to consider is resilience and maintenance. Climate-smart, disaster-resilient projects should be the norm, not the exception. Maintenance must be prioritized and funded—not treated as an afterthought.

Lastly, we must prioritize inclusive governance. Projects should include communities in the decision-making process. Infrastructure is not just about moving goods; it is about serving people.

A road to nowhere—or somewhere?

Bangladesh cannot allow infrastructure to continue being the primary obstacle in its development journey. The path forward requires not just more money, but smarter governance.

First, a unified vision or a single, coherent strategy for infrastructure is essential—one that aligns ministries, avoids duplication, and sets clear priorities. Piecemeal plans will only produce piecemeal results.

Second, we need stronger institutions. Agencies must be streamlined, responsibilities clarified, and accountability enforced. Overlapping mandates must provide a way to coordinate action.

Third are the twin pillars of governance—transparency and accountability. Public procurement must be cleaned up. Citizens should know where money is going, contracts should be awarded fairly, and corruption must be punished, not tolerated.

Fourth, we need to invest in our people. Training engineers, planners, and skilled workers is as important as pouring concrete. Retaining talent with fair pay and professional growth is vital.

The fifth aspect to consider is resilience and maintenance. Climate-smart, disaster-resilient projects should be the norm, not the exception. Maintenance must be prioritized and funded—not treated as an afterthought.

Lastly, we must prioritize inclusive governance. Projects should include communities in the decision-making process. Infrastructure is not just about moving goods; it is about serving people.

Habib Zafarullah

Dr. Habib Zafarullah has taught at the Universities of Dhaka, New England and Sydney. He has published extensively in democratic governance, public policy, and international development. His recent books include Governance and Sustainable Development in South Asia; Open Government and Freedom of Information; Handbook of Development Policy; and Colonial Bureaucracies. He has also published numerous articles and book chapters. E-mail: habibzed@gmail.com