Soon after the historic election of 7 December , 1970, I along with three of my classmates (Badrul, Habib, and Dulal) from Rajshahi Cadet College (RCC), went to Lahore to study there on “Inter-Wing Scholarships.” The education officials of Lahore who handled exchange of students between former East and West Pakistan, organized a warm reception in Lahore and praised students from East Pakistan for achieving excellent academic performance compared to West Pakistani students who went to study in former East Pakistan.

Lahore: The historic city infuses many culture

Over many centuries, the cultural and physical landscapes of Lahore were shaped by rulers who belonged to different religions and ethnicity-Hindu, Moghul, Persian, Afghan, Persian, Sikhs, and British. It is historically a city with famous tombs, mosques, forts, gardens, and parks, palaces, and museums.

Lahore represented the first site of Moghul conquest of India. Because of its strategic location between Mogul strongholds, the Lahore Fort was rebuilt by Emperor Akbar in 1566. The Shalimar Garden, another historical symbol and now a UNESCO world heritage site was built by Emperor Shah Jahan in 1641-42. It is a Mughal artistic landmark reflecting a Persian influence and medieval Islamic-garden traditions. The tombs of Emperor Jahangir and his wife Nur Jahan are located in Shahdara Bagh near Lahore. The famous Badshahi mosque in Lahore, built by Emperor Aurangzeb in 1673, epitomizes Mogul era architecture.

Rudyard Kipling, the British writer, Nobel Laureate, propagandist, apologist of British imperialism, spent his formative years (1882-1887) in Lahore which represented the centre of Kipling’s India. Lahore provided the setting and ingredients for Kipling’s great stories, poems, such as Kim, Ballad of East and West, White Man’s Burden, and his views about East and West. In the Ballad of East and West, he wrote the famous line which is often misinterpreted and misunderstood: “ Oh, East is East, and West is West, and never the twain shall meet.” Kipling highlighted the profound differences between East and West and the burden of civilizing mission of the West.

Historically, Lahore was the epicentre of politics in Pakistan. On 23 March, 1940, the famous Lahore Resolution was presented by Sher-e-Bangla Fazlul Huq, which called for the establishment of independent Muslim State(s) in India. In 1966 in Lahore, Sheikh Mujibur Rahman announced the 6-point proposal for the autonomy of East Pakistan.

Lahore Government College: Elite’s premier educational institution

A prestigious academic institution, Lahore Government College was the seat of higher education for many sons and daughters of the affluent landlords and elites of Pakistan. Its alumni include Poet and philosopher Allama Iqbal, Nobel Laureates Dr. Abdus Salaam and Dr. Khurana (later an Indo- American). Our classmates included a son of Hamoodur Rahman, at that time the Chief Justice of Pakistan. Hamoodur Rahman later headed the commission that investigated the debacle of Pakistan in 1971.

A prestigious academic institution, Lahore Government College was the seat of higher education for many sons and daughters of the affluent landlords and elites of Pakistan. Its alumni include Poet and philosopher Allama Iqbal, Nobel Laureates Dr. Abdus Salaam and Dr. Khurana (later an Indo- American). Our classmates included a son of Hamoodur Rahman, at that time the Chief Justice of Pakistan. Hamoodur Rahman later headed the commission that investigated the debacle of Pakistan in 1971.

In the dormitory of the College, an aura of feudal aristocracy prevailed: For every four students there was a servant who would keep the room and shoes clean and who would be ready to bring food from the cafeteria if anyone wanted. Student leaders of our Hall, one day welcomed us and assured all help and promised to arrange items of fish on the menu – a great promise in Lahore. The teachers of Lahore Government College were friendly to us, especially the English teacher who invited us a few times in his office for tea. He told us that he often listened to Tagore songs. However, when we went to see the Head of economics department, he looked like an old grumpy man. One day, in our mathematics class, the teacher, in the middle of his lecture, started lecturing in Urdu. He noticed us and inquired whether any one did not understand Urdu. I stood up and said that a few of us did not understand Urdu. Some Punjabi students murmured: “Why don’t you understand Urdu?” The teacher immediately switched to English which was the medium of instruction.

There were some Punjabi students who were too innocent of what was going on in the political arena. I still remember a student, who came from Sialkot, said: “How can East Pakistan separate from West Pakistan? We have the same Quran, the same Kibla, the same Prophet, and of course the same Islam.” I said to myself, the four sub-identities essentially amount to one identity. Increasingly, by the 1940s, the Islamic identity dominated the psyche of Muslims in the Indian subcontinent because of religious polarization often fanned by British policy of divide and rule. However, since the late 1950s, in East Pakistan, the Bengali identity resurged fuelled by economic exploitation of East Pakistan and cultural domination of East Pakistan by West Pakistan. Other ethnic identities also re-emerged in West Pakistan. Not surprisingly, students from the Frontier Province, Baluchistan, and Sind at Lahore Government college eagerly welcomed the prospect of Mujib becoming the Prime Minister.

Our memorable days in Lahore

While we were in Lahore, an incident happened on 30 January, 1971, which dramatically worsened the India-Pakistan relations. A group of Kashmiri militants hijacked an Indian plane, brought it to Lahore and set it on fire. The people of Lahore in great jubilation welcomed the militants as heroes. India immediately banned all Pakistani flights over the Indian air space. All flights from West Pakistan and East Pakistan were routed through Karachi and then over Sri Lanka. Later it was alleged that the entire incident was carefully plotted by the Indian Intelligence Branch; however, India denied it.

One day, while we went to shopping, a Punjabi business man asked us whether we were from East Pakistan. As soon as we uttered yes, the man started making a vilifying speech against the Bengalees. Apparently, his business was vandalized in Dhaka. He took a piece of paper and said, “You want independence, then have it.” We firmly but politely calmed him down and reminded him that: “East Pakistanis are the majority demographically and now politically. We have no reason to ask for independence. If you West Pakistanis want independence, then go and tell your army generals.”

The most surprising and memorable event in Lahore was our meeting with Major Khaled Adib who was our first Adjutant at Rajshahi Cadet College (RCC). After leaving RCC, he was posted at the Lahore Cantonment. He invited us twice, one in Lahore Inter-Continental Hotel and another probably in the Cantonment. A truly broad-minded person, at one time during our conversation, he suddenly, made a statement which proved to be prescient: “Gentlemen, East Pakistan soon is going to be an independent country. You should develop a very strong army.” We still could not figure it out whether he had any advance information or he was saying this on the basis of his intuition.

On 28 February, 1971, while we were in Lahore, Z.A. Bhutto gave his politically most combustible and demagogic speech at a mammoth public meeting in Lahore. I thought about attending it; however, later I abandoned the idea because occasionally, we were jeered by the Punjabi people on the street: “Hey Benglee Babu!”

The political situation worsened sharply following the speech on first March, 1971, by General Yahya, essentially caving in to the pressure from Bhutto. He indefinitely postponed the scheduled meeting of the National Assembly which was supposed to be held on third March in Dhaka. Punjabi students in the Common Room thunderously applauded the speech of Yahya and thought Mujib would get the lesson soon. On 7 March the Common Room was full to hear the contents of Mujib’s speech. Hearing the tough speech of Mujib, the Common Room fell into a complete silence.

Increasingly, it became clear to me that the days of a United Pakistan were numbered and that the existential crisis of Pakistan had reached a dead-end. As far as I remember, on 22 March, 1971, we decided to leave Lahore for Dhaka without telling the authorities of Lahore Government College. We took a flight to Karachi, stayed overnight in the Karachi Cantonment where our friend Badrul’s brother was an army officer. On 23 March, a historic day, which is called the Pakistan Day (formerly the Lahore Resolution Day), we boarded on our flight to Dhaka. At the Karachi Airport, an airport official asked, “Are you going to Dhaka to make Sheikh Mujib’s hands strong?” One of us immediately retorted: “He is already strong.”

Kushtia’s best of times and worst of times

On 24th March, I left Dhaka for Kushtia to visit my eldest brother who was a doctor at the Kushtia Sadar Hospital. The next day, Pakistan’s brutal “Operation Search Light” began in Dhaka. Kushtia, although a small district at that time, became the bastion of the liberation forces. For a brief account of the liberation war in Kushtia, one can read the article, “The Battle of Kushtia”, by the correspondent Dan Coggins, Time magazine, 19 April, 1971. As the Pakistani forces advanced

On 24th March, I left Dhaka for Kushtia to visit my eldest brother who was a doctor at the Kushtia Sadar Hospital. The next day, Pakistan’s brutal “Operation Search Light” began in Dhaka. Kushtia, although a small district at that time, became the bastion of the liberation forces. For a brief account of the liberation war in Kushtia, one can read the article, “The Battle of Kushtia”, by the correspondent Dan Coggins, Time magazine, 19 April, 1971. As the Pakistani forces advanced

toward Kushtia, probably on 17 April, 1971, we took shelter in our maternal uncle’s house in Khoksa (about 24 kilometres, south-east of Kushtia, near Gorai River) where Rabindranath Tagore wrote a few poems. For several months, we were stuck in Khoksa; my family members in Shibganj Upazilla in Chapai Nawabganj thought I was still trapped in Lahore!

One day, a gang of Biharis and other collaborators, escorted by Pakistani Army persons came to Khoksa. Their main targets were Hindus, freedom fighters, and university students. I, along with my relatives, took shelter in another village. Next day, we returned to my uncle’s house. With great risk, my uncle (who ironically was, in a way, “a persecuted Muslim” emigrant from Murshidabad) gave shelter to some prominent Hindu families. The Pakistani army and their collaborators took away some Hindus and killed several of them.

Next day, we went to a nearby sugarcane field where we saw two dead bodies with slitted throats. The slaughtered men were innocent Hindus who used to make a living by carrying out menial jobs. To me, after almost 52 years, those slitted throats still evoke vivid yet horrific images of the barbarity of the Pakistani Army. In Khoksa, one day, I also went to see the bullet-ridden dead body of a local “Peace Committee” leader. Just a few days before he was killed, he showed us a letter of death-threat from the Mukti Bahini.

In Kushtia, to use an expression of one of my favourite novelists – Charles Dickens, I saw the best of times as well as the worst of times. I saw the poorest of poor families serving cooked food for liberation forces. I saw how in the absence of police and other government forces, for a brief period, a free Kushtia remained free from petty crimes and also free from self-serving impulses. I saw the worst of times when I saw those slitted throats and when I learned that there was no shortage of collaborators whose job was to slaughter and torture fellow human beings. I also heard about how some innocent Biharis were butchered in North Bengal. As if, for some time, we were in a “Hobbesian jungle.”

Innocent victims: Stories untold

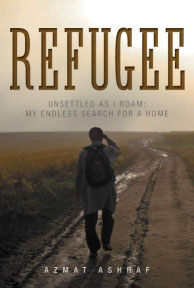

Indeed, after the liberation war was over, I heard about many horrific episodes involving innocent victims including my cadet college friend Azmat Ashraf who came from a Urdu- speaking family in Thakurgaon. Hayatt Ashraf, Azmat’s father, migrated to East Pakistan with his family in 1953 from his ancestral village Kumhrauli in Darbangha, Bihar to escape from persistent discrimination against Muslims in India. In Tahkurgaon, Hayatt Ashraf consciously inculcated his children with strong family values and Bengali language and culture. Unfortunately, during the turbulent days of 1971, Azmat’s siblings, parents, and close relatives were brutally killed just because they were labelled as Biharis. Azmat’s younger brother Hasnat had to cross the border and returned to his ancestral village in Bihar. Being in Karachi, Azmat escaped the great tragedy.

After living in Pakistan and UK, Azmat and his younger brother settled in Canada. After retiring from a successful banking career, Azmat painstakingly collected relevant information and has written a book Refugee :Unsettled as I Roam: My Endless Search for a Home. It is a heart- wrenching memoir which I finished reading in one night. Ironically, Azmat provided help and guidance to two of our cadet friends, who were in Pakistan Army, in crossing the Indian border to join the liberation war. Despite the great tragedy, Azmat remains an eternal optimist and contributes to various social projects in various countries including Bangladesh.

After living in Pakistan and UK, Azmat and his younger brother settled in Canada. After retiring from a successful banking career, Azmat painstakingly collected relevant information and has written a book Refugee :Unsettled as I Roam: My Endless Search for a Home. It is a heart- wrenching memoir which I finished reading in one night. Ironically, Azmat provided help and guidance to two of our cadet friends, who were in Pakistan Army, in crossing the Indian border to join the liberation war. Despite the great tragedy, Azmat remains an eternal optimist and contributes to various social projects in various countries including Bangladesh.

Author Azmat Ashraf was one year old when his family escaped India in 1953 for the relative safety of East Pakistan. This book is a story of human resilience in the

face of evil, of real love and true friendship, and an inspiration for refugees everywhere who are struggling to find a place of security and prosperity in this troubled world. Despite his family’s personal tragedies, Azmat has taken great care to provide a balanced view of the conflict of 1971 to help Pakistanis and Bangladeshis in particular and people of the subcontinent in general understand this painful part of their mutual history.

Joys of victory

Probably at the end of August of 1971, we decided to leave Khoksa and went to Chapai Nawabganj town where we stayed until the end of December. The greatest moment, of course, came on 16 December, 1971, when the “Mukti Bahini” liberated Chapai Nawabganj. While liberating Chapai Nawabganj, Bir Sreshstha Mohiduddin Jahangir was killed on 14 December.

On 16 December, the news quickly spread about officers of the liberation forces, which to my surprise and ecstasy included Bazlur Rashid, a classmate from RCC. I went to the makeshift headquarters of the liberation forces where I was overjoyed to meet Bazlur Rashid. The commander of the liberation forces invited me as a special guest to the lunch party. Bazlur Rashid, possibly with a few others, deserted the military academy in Pakistan, crossed the India-Pakistan border with an enormous risk, and joined the liberation war. From the information that I have, Bazlur Rashid served as the commander of one of the three groups assigned to liberate Chapai Nawabganj. He was the commander of sub-sector 6 (Sheikhpara) in Sector 7. After a few years, when I met him at the Dhaka Airport, he indicated he was disgruntled and disillusioned. He left the Army and,as far as I know, worked at the Rural Electrification Board and unfortunately, died prematurely.

Our joyous moment in Chapai Nawabganj was punctuated by a grim news. One of our cousins, a brilliant student of the engineering university in Dhaka (now BUET) became a martyr in the liberation war and was not among those hundreds of fighters who victoriously returned from the battlefields and entered Chapai Nawabganj. I never had the courage to see my beloved Khala Amma and console her. I never found a manual or a book that would have taught me how to console a grieving mother. As the Victory Day appears every year, I cannot but recall the imaginary stoic face of my Khala Amma. Today, a hall named after him (Satu Hall) in Chapai Nawabganj, reminds us his heroism and sacrifice.

Epilogue

Pakistan imploded in 1971 because of its internal contradictions driven by geographical absurdity, profound cultural and language differences, ignorance, and myopia of the military-capitalist class of West Pakistan. To rephrase Rudyard Kipling: “Oh, East Pakistan was Bangladesh, and West Pakistan was Pakistan, and the twain were doomed not to integrate.

As I philosophically reflect upon events of 1971 and the Victory Day, it appears to me that in the short-run, self-delusional and power-hungry rulers can hang on to power through divide and rule, rhetoric, and deception, but in the long-run, the forces of good triumph over forces of evil. Yet, the liberation struggle in Bangladesh is not yet complete. Let the Liberation War and the Victory Day remind us that liberation struggle is not a “destination” but a “perpetual mission” against poverty, malnutrition, corruption, unequal access to educational opportunity, subhuman working conditions, exploitation, and illiteracy. More importantly, let’s keep up our “inner liberation struggle” by tilting our mindset toward empathy for the less fortunate.

Note: A different version was published in May 2016 in Bdnews24.com

Sadequl Islam is a professor and former Chair of economics at Laurentian University, Ontario, Canada. He has an MA and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. He also has an MA in economics from Dhaka University. His research and teaching fields include macroeconomics, international economics, applied econometrics, and the Chinese economy. His publications include many articles in scholarly journals and a book The Textile and Clothing Sector of Bangladesh in a changing World Economy published by the Centre for Policy Dialogue and the University Press. He was a visiting scholar at El Colegio de Mexico, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), and the Centre for Policy Dialogue. E-mail: sislam@laurentian.ca