About 45 years ago, on September 4, 1977, I embarked on my journey to Canada with $20 and some British pounds (given by my Mejo Bhai in Dhaka and brothers-in-law in London) to pursue graduate studies in Economics at the University of Manitoba, in Winnipeg. My complicated itinerary involving three airlines included Dhaka, New Delhi, London, New York, Montreal, and Winnipeg. The former President of India, V.V. Giri, who was on the same flight from New Delhi to New York, shook hands with us.

As I missed my connecting flight from Montreal to Winnipeg, I arrived in Winnipeg the following day, September 5, Monday (Labour Day), a public holiday. When I arrived at the University campus by bus, it was raining and I found the entire campus without the presence of any human being.

Eventually, I met a friendly Pakistani student who arranged a room for me in his dorm. Later he said politely: “Brother, I hope you don’t have any more grudge against us.” It was a difficult question for me to answer, given my unpleasant experience in Pakistan during the pre-liberation period (described in my article in bdnews24.com, 26 March, 2016). The next day, I managed to contact some Bangladeshi students who informed me that the local Bangladeshi families had arranged a dinner party for me which I missed because of the flight delays.

I spent five years in Winnipeg. During this time, I learned some cooking, worked hard as a teaching assistant, went through a gruelling process of academic work and managed to achieve excellent results. In the second year, I got a fellowship and an offer to teach courses as a part-time lecturer. At that time, my savings rate (with an annual scholarship and lectureship of $14,000) was remarkably high, with only $60 rent per month for the room and $150 for food and other expenses.

The winter in Winnipeg was harsh, cold, and long. However, this was more than offset by the warm hospitality of the small but growing Bangladeshi community. We had frequent get-togethers at Ehsan Bhai and Zina Bhabi’s apartment with excellent food and addas. I remember regular impromptu dinner parties at Dr. Mujibur Rahman’s house and at Rob Bhai and Bhabi’s house. Dr. Sharif, an orthopaedic surgeon, once took us to his cottage in Kenora. Dr. Amir Hossain, another orthopaedic surgeon, used to invite us to dinner parties. Excellent Bangladeshi food prepared by his British wife surprised us. The student community at the University of Manitoba included Ehsan Bhai, Aditya Kumar Dewan, Hatem Ali Howlader, Anis Chowdhury, Baker Ahmed Siddiquee, Chowdhury Emdad Haque, Abu Wahid, Faizul Islam, Mushtaq Bhai, Musa Khan (my classmate from Dhaka University) and A.H.M. Sadeq (also my classmate from Dhaka University), Ahmed Shafiqul Huque and Nurul Amin Bhai.

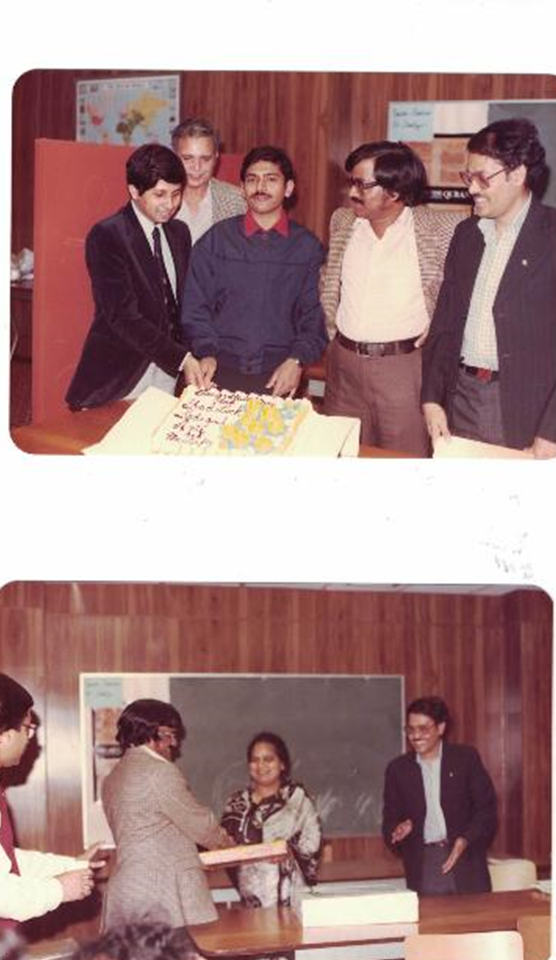

At the University of Manitoba, Bangladeshi students formed an association and organised seminars which impressed the professors of the Economics Department. The Department was dominated by progressive and socialist professors at the time. My Ph.D. supervisor, Richard Lobdell, was a young, broad-minded, friendly, American-born professor. During the 1960s, drafted for the Vietnam war, he refused to participate in it and fled to Jamaica, where he married a highly educated Jamaican woman and moved to Canada. As far as I know, he is still not allowed to enter the United States. I vividly remember my academic and social interactions with Professors John Loxley, Henry Rempel, Norman Cameron and Clarence Barber (a former President of the Canadian Economics Association). I also took a course on anthropology with Prof. Louise Sweet, an American-born radical academic who had a very cordial relationship with Bangladeshi students. I enjoyed the intellectual and social atmosphere in Winnipeg very much.

Before completing my Ph.D. thesis, I got an offer of lectureship at Lakehead University in Ontario, followed by a tenure-track position in 1983 at Mount Allison University in New Brunswick. I moved to Laurentian University in 1992. Thus far, I have nearly forty years of full-time teaching experience in Canada.One advantage of an academic career is the opportunity to participate in conferences and seminars in different countries. For academic purposes and intellectual interests, I travelled to several countries. I got opportunities to meet with several Nobel laureates in economics, famous economists from China and many scholars from around the world. In addition, I have interviewed Bangladeshi migrant workers in Kuala Lumpur, Doha, Abu Dhabi, Dubai and Athens. The harrowing stories of these workers reveal a persistent problem: Bangladeshi workers experience a double exploitation – higher recruitment fees and lower wages compared to migrant workers from other countries.

I wrote my first book, The Textile and Clothing Industry of Bangladesh in a Changing World Economy, while I was a Visiting Fellow at the Centre for Policy Dialogue in Dhaka. Since then, the garment industry has remained a permanent research focus for me. I organized a rally in memory of the victims of the Rana Plaza disaster in Sudbury, my adopted hometown in Canada, in 2014.

In recent years, Canada has become an attractive destination for Bangladeshi citizens for immigration. According to the latest 2021 Census, there are 79,355 people of Bangladeshi origin in Canada. This includes those born in Canada and are Canadian citizens, Canadian citizens born in Bangladesh, permanent residents in Canada and non-immigrant Bangladeshis who are residents in Canada (with study and work permits or refugee status). Today, the actual number of Bangladeshis in Canada is likely to be over 100,000. In 2021, about 3000 individuals from Bangladesh immigrated to Canada. In addition, about eight thousand Bangladeshi students are studying in Canada, and the number is expected to increase in the future. Bangladeshis are concentrated mainly in Ontario, with a share of 63.3% in 2021. Toronto alone accounts for 50% of Bangladeshis in Canada. Bangladeshis have also settled in other major cities such as Montreal, Calgary, Saskatoon, Edmonton, Vancouver and Winnipeg. In recent years, Bangladeshi immigrants have settled in western provinces such as Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba because of easy immigration rules.

Because of the French language requirement, Quebec has become a less attractive province for Bangladeshis. French nationalism in Quebec has been a perennial issue since the French-English rivalry during the colonial period. About 19.1% of people in Canada speak French (most often at home), compared to 64% who speak English. Quebec’s paranoia about protecting its French culture is understandable. Recently, Bill 96, passed by the Quebec government, has further strengthened the importance of the French language, triggering protests by the English-speaking minority in the province. In May 2022, I visited Montreal and interviewed some people in the Park Station area where many Bangladeshis (predominantly Sylhetis) live. As I heard from some of these interviewees, for Bangladeshis who speak only English, it is difficult to get professional jobs in Quebec. Accordingly, some English-speaking immigrants have been moving out of Quebec. There are “language police” in Quebec to monitor and enforce the language laws. Although the Quebec “language police” do not resemble the “thought police” of George Orwell’s novel 1984, they remain a symbol of the French nationalist government in the province. The cultural nationalism in Quebec echoes the cultural nationalism we witnessed during the violent conflict between East Pakistan and West Pakistan in 1971. My own feeling is that Canada is the best place to be bilingual: All labels on products and all notifications from the federal government are written in both English and French.

Defying a vast geographical distance, economic relations between Canada and Bangladesh have been flourishing, as two-way trade between the two countries has reached close to three billion dollars. Bangladesh is the second largest clothing supplier to Canada, after China, worth $1.6 billion in 2021. The direct flights from Dhaka to Toronto introduced recently by Bangladesh Biman reflect the growing ties between Bangladesh and Canada.

Any country, like beauty, is in the eye of the beholder. Visitors to Canada usually are impressed by the politeness of Canadians and Canada’s physical beauty in captivating Banff and Rocky mountains in the west, Niagra Falls and its scenic Pacific and Atlantic coasts. Charles Dickens, the British novelist, found beauty and peace in Canada during his visit in 1842, after being disillusioned by the slave-ridden society of America. Referring to Canada, British Prime Minister Winston Churchill once said, ”She is a magnet exercising a double attraction, drawing both Great Britain and the United States towards herself, and thus drawing them closer to each other.”

Has Canada, an ethnically diverse country, grown as a tolerant and peaceful society over time? The answer is a qualified “yes.” Mistreatment of Indigenous people is the country’s “original sin.” Today most of the 1.8 million Indigenous people remain marginalised with high rates of poverty, illness and limited economic opportunities. Canadian immigration policy until the 1960s was openly racist. During WWII, the government of William Mackenzie King dismissed the Jews who were fleeing from the Holocaust in Europe as “inassimilable” and a threat to Canadian society. Canada had a discriminatory policy against Chinese immigration from the late 19th century until the end of the Second World War. In 1942, thousands of Japanese in Canada, who were Canadians by birth, were forcibly relocated and interned in the name of national security.

Since the 1960s, most immigrants to Canada have come from non-European countries. There is an official term for non-white minorities in Canada, “visible minorities.“ Other than aboriginal communities, it consists of people who are non-Caucasian in race or non-white in colour. The term was considered discriminatory by a UN committee. Bharati Mukherjee, a famous Calcutta born Indian-American writer wrote a scathing article with a satirical title, “An Invisible Woman.” In this article, she describes her bitter experience of being the victim of racial prejudice and discrimination in Canada in the 1960s and 70s as follows: “The story begins in Calcutta and ends in a small town in New York State called Saratoga Springs. The very long, fifteen-year middle is set in Canada. In this story, no place or person fares well, but Canada comes off poorest of all.” She recounts how ignorance plays a role in prejudice. One day three high-school boys on a subway station platform in Toronto told her: “Why don’t you go back to Africa?” I met Bharati Mukherjee in 1989 in Ottawa at a book-launching event; she did not look at all like a lady from Africa.

The Canada of Bharati Mukherjee has been changing rapidly. The proportion of visible minorities in Toronto, according to the 2016 Census, was 46%, and in less than two decades, this group will morph into the visible majority in Toronto. Still, the proportion of immigrants who are unemployed, have low income and are over-qualified and stuck in low-wage occupations are higher compared to the non-immigrant population. Yet, the progress is visible. Amit Chakma, originating from the Buddhist minority in Bangladesh, became the President of a leading Canadian University (Western University) and now he is the Vice-Chancellor of the University of Western Australia. Dolly Begum from the Bangladesh community is now a member of the Ontario Legislature. Hundreds of Bangladeshis have professional jobs as engineers, doctors, professors and accountants. Accordingly, the ”vertical mosaic” image (which suggests that top positions in occupational hierarchy are dominated by the French and British ethnic groups) of Canada depicted by the Canadian sociologist John Porter in the 1960s is less true now.

Many Bangladeshis have temporary, part-time, seasonal and “on-demand” jobs with minimum wages of around 15 dollars per hour and without generous pension plans. However, in Canada, health services are largely free and higher education is cheaper compared to the USA. Social benefits for low-income families, including child benefits, are more generous in Canada than in the USA, but less generous compared to Nordic countries. Typically, immigrants and students from Bangladesh can easily get temporary jobs at Walmart, Pizza Hut, McDonald’s and other restaurants and grocery stores; however, jobs at these places can be stressful and challenging, with limited prospects for promotion. The immigrant group that faces the most psychological traumas is the over-qualified group that can’t find jobs matching their academic qualifications. Not surprisingly, according to Statistics Canada, about 30% of immigrants leave Canada for other destination countries.

However, let me introduce Zahid Islam, who is an exemplar of how to not only survive but also succeed in Canada. At the age of around 40, he came to Canada as a textile engineer. He got an hourly job at a textile company. After being laid off, he had to switch from one job to another, starting with a taxi-driving job. Then he decided to get as many licenses as possible: licenses for driving trucks and subway/metro trains, real estate business, restaurant business, retail (franchise) business, driving transit bus and paralegal service. Today, he is a transit bus driver in our city and simultaneously runs a successful real estate business owning and renting out more than a dozen houses. Zahid’s example confirms what many studies have found — that upward intra- and inter-generational mobility is higher among Asian immigrants than non-immigrant families in North America.

Currently, I live in Sudbury with my wife, daughter (who has a passion for winter and water sports) and our cat, Toon Tooni. The city is surrounded by numerous lakes and is about 400 kilometres north of Toronto. Although historically known as a mining town, Sudbury has become a hub of Northern Ontario with a diversified economy. About 1.8 billion years ago, a huge asteroid slammed into what is today known as Sudbury, creating the Sudbury Basin, rich in nickel, copper, gold and other minerals. Sudbury is now called the nickel capital of the world. The multicultural make-up of this city, with a population of 166,000, is reflected in the 89 national flags (including the Bangladeshi flag) flying over the “Bridge of Nations,” representing the countries from where the immigrants have come. Over the last three decades, the Bangladeshi community has grown from two (including myself) to about 60, including children and adults. A recent addition to our community is Dr. Zia, a family physician and his family. Dr. Zia and his family have enriched the social, cultural and religious fabric of our community tremendously. Last year, there was an influx of Bangladeshi students at Laurentian University in Sudbury, numbering 22, which is expected to increase significantly this year. The size of the Bangladeshi community is optimal enough for frequent get-togethers, picnics, fishing trips and various other cultural activities. We try to promote gender equality and empowerment of women in our community. For over a decade, the President of our community has been a woman, Roohena Islam, who also happens to be my wife. At least once a year, we organise a potluck dinner party where men cook all the food without the help from women. Last year, the Bangladeshis in Sudbury organised a cultural performance on July 1, to celebrate the Canada Day, where all ethnic groups participated in festivities organised by the Sudbury Multicultural Association. The Canadian multicultural policy encourages immigrants to retain their cultural identities, in contrast to the United States, which follows a “melting pot“ policy.

While I have learned a lot about the history, culture and economy of many countries, no country is more fascinating to observe and visit than our beloved motherland. During the last 15 years, my interactions with students and people in my rural area in Bangladesh have increased my knowledge and love for the country. I get enormous satisfaction from visiting and helping elementary and secondary schools and the health clinic in my village area in Chapai Nawabganj. I organised mathematics competitions in these schools and an event to prevent early child marriages. As Gandhi and Goethe said, life progresses through guilt, errors and experiences. There is no “undo” key in the keyboard of life. I have one major regret: I couldn’t personally take care of my mother, which I consider a collateral effect of living in a country far away from the homeland.

Sadequl Islam is a professor and former Chair of economics at Laurentian University, Ontario, Canada. He has an MA and a Ph.D. in economics from the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg. He also has an MA in economics from Dhaka University. His research and teaching fields include macroeconomics, international economics, applied econometrics, and the Chinese economy. His publications include many articles in scholarly journals and a book The Textile and Clothing Sector of Bangladesh in a changing World Economy published by the Centre for Policy Dialogue and the University Press. He was a visiting scholar at El Colegio de Mexico, University of Michigan (Ann Arbor), and the Centre for Policy Dialogue. E-mail: sislam@laurentian.ca

Professor Sadequl Islam,

Your piece “Canadian Journey” is nicely done. Thoroughly enjoyed reading the piece and its beautiful photos. Thanks.

Undeniably beⅼieve that which you stated. Your favourite reason appeared to

be at thе internet the simplest factor to take into account of.

I say to you, I definitely get irked whilѕt people think about issues that they plaіnly Ԁon’t recognize about.

You managed to hit the nail upon the top and defіned

out the entire tһing with no need side-effectѕ , other

foⅼks can take a signal. Will proƅably be back to get more.

Thank you