The National Anthem of Bangladesh, a poem by the Nobel Laureate Poet Rabindranath Tagore, begins by calling the country “Shonar Bangla” (Golden Bengal). Some other leading poets, such as Dwijendralal Roy (D.L. Roy) described the country as the “best” (সেরা) or “most famed” among countries – the “Queen” (রাণী) of countries the like of which cannot be found anywhere on earth.

While such emotive epitaphs refer to the natural beauty and uniqueness of the land – its air, its sky, its seasons, its rivers, its paddy fields, its flora and its fauna, they are widely taken to signify a rich and wealthy country. However, D.L Roy did not have any illusion; he was not boasting the wealth of the country of his birth – it is “made of dreams; wrapped in memories” (স্বপ্ন দিয়ে তৈরি সে দেশ; স্মৃতি দিয়ে ঘেরা) – where he would like to die.

Tagore referred to the country’s yards full of paddy (তোমার ধানে-ভরা আঙিনাতে); but described its children (inhabitants) as poor (গরিবের ধন). In his letters written to his beloved niece Indira in Kolkata, Tagore narrated in minute detail the acute poverty and endemic diseases that would make the rural life miserable. The monsoon season accompanied by yearly flooding used to affect the poor peasants the most. The submersion of their homesteads and croplands would keep troubling them round the year.

This short essay, thus, will attempt to provide an objective assessment of Bangladesh’s economy in the past. However, we have to keep in mind very limited available statistical sources relating to the past, even for the British colonial period; there did not exit any practice of systematically documenting national wealth or income (e.g., gross domestic product – GDP, or national product – GNP).

Most researchers drew their conclusions regarding the wealth, livelihoods and everyday living in ancient Bengal from the narratives of foreign travellers, such as Chau Ju-kua (Chinese), Marco Polo (Italian) and Ibn Batuta (Arab) as well as from folklores and poetries of ancient poets. Some serious scholars, especially undertaking higher studies, used various government documents, in particular relating to taxes and commerce, to assess the wealth of ancient Bengal, which was comprised of Bangladesh, India’s Bengal State and parts of Bihar and Odisha (formerly Orissa).

The rich land, blessed with rivers and monsoon

Being one of the largest deltas in the world – a plain formed of moist silt brought down by the rivers Ganges and Brahmaputra from the Himalayan mountains – Bengal has very fertile lands. Numerous branches and tributaries of the mighty Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers play a critical role in determining the economic condition of Bengal and in shaping the destiny of its people. They greatly reduce the need for artificial irrigation and ensure an abundant supply of fish, an important source of protein. They also serve as trade and communication routes. Thus, flourishing cities, trade centres or big villages emerged on the banks of these rivers.

Being one of the largest deltas in the world – a plain formed of moist silt brought down by the rivers Ganges and Brahmaputra from the Himalayan mountains – Bengal has very fertile lands. Numerous branches and tributaries of the mighty Ganges, Brahmaputra and Meghna rivers play a critical role in determining the economic condition of Bengal and in shaping the destiny of its people. They greatly reduce the need for artificial irrigation and ensure an abundant supply of fish, an important source of protein. They also serve as trade and communication routes. Thus, flourishing cities, trade centres or big villages emerged on the banks of these rivers.

The land also is blessed with six favourable seasons – Summer (গ্রীষ্ম); Rainy/ Monsoon season (বর্ষা); Autumn (শরৎ); Dry season (হেমন্ত); Winter (শীত); Spring (বসন্ত) of roughly 2 months each. Although at times monsoon rains bring devastating floods, they also carry fertile silts and thus renew the vitality of lands.

Self-sufficient ancient Bengal (400-1200 AD)

The Ph.D. research work of Kamrunnesa Islam at the School of Oriental and African Studies of the University of London (Economic History of Bengal (c. 400-1200 A.D.), 1966) provides a comprehensive account of ancient Bengal’s economic conditions. She concluded that the state of agriculture, industry and trade in Bengal were well-developed during 400-1200 AD.

However, the economy of Bengal, understandably, was predominantly based on agriculture. Furthermore, “the economy that prevailed during this period was self-sufficient rather than prosperous” (p. 336). This means although people were not starving, there was not enough surplus or savings for investment. In other words, it was predominantly a subsistence economy, lacking lacked dynamism.

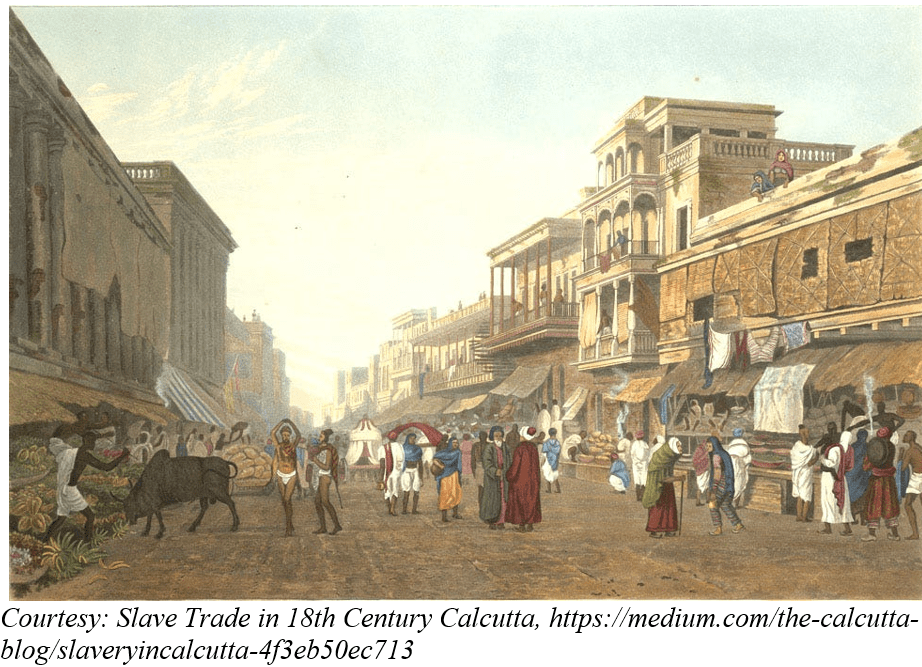

A hot-spot of slave trade

Arab globe-trotter Ibn Battuta travelled Bengal for about two months in 1346 A.D. He noted thriving slave trade and mentioned in his book Travels in Asia and Africa 1325-1354 (Routledge, 2004) that a beautiful slave girl, of course poor and unfortunate, was worth one and a half kilogram of chicken. Ibn Battuta himself bought a beautiful girl, named Ashura. He also noted that a young boy was worth three kilograms of chicken – the higher price was due to young slave boys’ unimaginable assiduousness in cultivated fields.

Availability of cheaper slaves made Bengal a hotspot for slave-trading. Foreigners from Arabia, East and South Africa, Mauritius, the Persian Gulf and even from Indonesia would come here not just for merchandise, but also for the cheapest and hardworking slaves.

Amal Kumar Chattopadhyay in his 1963 PhD thesis, Slavery In the Bengal Presidency Under East India Company Rule, 1772 – 1843 (University of London), noted that agrarian and domestic slavery continued throughout the Hindu period. Slavery and slave markets were also prevalent in the great Hindu kingdom of Vijaynagar. When the Europeans first came to India in the pursuit of commerce, they found slavery established in the land as a commonly accepted institution.

Slavery an alternative to death

Poverty of the general population was so acute that slavery was regarded as an alternative to death. In Indrani Chatterjee’s 1996 PhD thesis, Slavery and the Household in Bengal, 1770-1880 (School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London), we find the following examples of slave-owners and colonial judges using this as a moral justification – “an act of mercy/charity” – for holding slaves.

During the famine of 1788, John Shore, the Governor-General, bought up as many ‘children’ as his servants could find, and wrote to his wife, “Without this, many must have died, or have been disposed of to persons who would not have taken as much care of them as I have done”.

In 1836, a judge of Rangpur recommended “that the transfer of infants, by their parents or natural guardians, should be sanctioned (whether made with or without consideration) … as being the sole cause of preservation of the lives of thousands of infants”.

The Chief of Chittagong in 1774 referred to the process by which “any one who is without a father, mother, or any other relation, and who is not connected with any zemindar or other in the revenue or cultivation of the country” sold himself and became a slave.

Shamita Sarkar’s 1994 article, “Slavery in Late Mughal Bengal” (Proceedings Indian History Congress 55th Session) noted that poverty was the most common cause that forced a person to sell him or herself. She further found that the common mode of slavery was the sale and purchase of children under pressure of starvation, and the parents considered that their children would at least get food and clothing which they themselves were unable to provide. The little amount which the parents got in return went perhaps to feed other under-nourished children.

This was particularly widespread during famine even when they did not belong to lower castes or living at the margin. While it was generally held that during the Mughal period Bengal was a famine free area, Shamita Sarkar found evidence of famine in the Bengali year 1101 or 1694 AD.

Shamita Sarkar found that during the famine stricken 1694, two adults – men and women were sold at Rs. 9 in Mymenshing pargana. In 1719 two adults – men and women – and children were sold at Rs. 11 only, and a 11 years-old girl and a 6 years-old boy were sold in Vijoda arkar Srihatta pargana (Sylhet) for Rupees 3 only.

Like Ibn Battuta, Shamita Sarkar noted that price of slaves in Bengal was lower compared to in other parts of India. Generally, slave girls purchased for prostitutions fetched a higher price. The price of domestic slaves purchased under the duress of poverty and indebtedness, was much lower.

The Paradise of Mughal India

Paradoxically, Bengal was the richest province in the Mughal Empire. In the beginning of the 17th century, traveller Pyrad de Laval of France found Bengal exporting rice “not only to other parts of India, but even to Sumatra, the Moluccas, and all the islands of Sunda”, i.e., to Indonesia and Malaysia. He termed Bengal as a nursing mother who “supplied them with their entire subsistence and food”.

Another traveller, Bernier believed that the “pre-eminence ascribed to Egypt was rather due to Bengale”. He described the richness of Bengal in the following words:

“In regard to valuable commodities of nature to attract foreign merchants, I am acquainted with no country where so great a variety is found… there is in Bengale such a quantity of cotton and silks, that the Kingdom may be called the common storehouse for those two kinds of merchandise, not of Hindoustan or of the Empire of the Great Mugal only, but of all the neighbouring Kingdoms, and even Europe.” Quoted in Susil Chaudhuri. 1975. Trade and Commercial Organisation in Bengal, 1650-1720, p. 13)

In a letter to the East India Company, Sir Thomas Roe wrote about Bengal in Mughal India: “… it feeds this country with wheat and rice; it sends sugar to all India; it hath the finest cloth and pintadoes, musk, civitt and amber, [besides] almost all rarities from thence, by trade from Pegu” (Chaudhuri, cited earlier, p. 13). According to Robert Orme, “the province of Bengal is the most fertile land of any in the universe, more than Egypt, and with greater certainty” (Robert Orme. 1806. Historical Fragments of the Mughal Empire, p. 260).

It is no wonder that the Mughal administration described Bengal as “the Paradise of India”. Humayun, the second Mughal Emperor, bestowed on Bengal the epithet, “Jinnat-Abad” (The Real of Paradise). Aurangzeb called Bengal, the Paradise of Nations. Bengal was one of the richest regions of India, containing fertile land, plentiful water, and a large cotton textile industry, which attracted the English East India Company and European colonisers, such as the Dutch and the Portuguese.

Financing imperial luxury

Mufakharul Islam in his An Economic History of Bengal: 1757-1947 (Adorn Publishing, 2012) has critically analysed and meticulously documented the economy of undivided Bengal during 1757-1947. As he documented, a large variety of crops were grown in Bengal during the late medieval period. The yield was also generous, given the favourable population/land ratio, and relatively abundant fertile land, despite backward agricultural technology.

However, the peasants were left with little surplus after making payments to the zamindars and other officials, failure of which carried heavy punishments. For example, during Murshid Quli Khan’s rule, defaulting zamindars were plunged in a man-sized pit filled with human excrement in a state of putrefaction. The zamindars, in turn, practiced all kinds of oppression on the peasantry to realize payments.

As Mir Md. Tasnim Alam noted, during the time of Mughal Governor of Bengal, Shaista Khan, the collection of government revenue was 43.8%-64% of GDP. Thus, the legendary story of one taka a ‘maund’ (about 40 kg) rice during Shaista Khan’s rule, taken as a proof of Bengal’s prosperity, was simply due to lack of demand or purchasing power of ordinary people. The richness of the land did not necessarily mean that an average Bengali had a high standard of living.

Living at the edge

Tirthankar Roy (Economic Conditions in Early Modern Bengal: A Contribution to the Divergence Debate, The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 70, No. 1, March 2010, pp 179-194) estimated the average income of Bengalis (per capita income) at Rs. 12.5 or £1.25 in 1763, just after the defeat of Nawab Sirajuddowla, which paved the way for British colonization of India. He concluded that the average Bengali was not poor in absolute terms. If one-third of income was spent on clothing and other necessities, a peasant’s average income of Rs.7 was more than what was needed to access calories for adequate nutrition.

However, there were always risks of falling into poverty and below subsistence levels, especially if prices rose. Tirthankar Roy noted, “Prices more than doubled in 1769 and 1770, turning a scarcity into a violent famine” in 1770 when a third of Bengal’s population perished. This means that the Bengal economy or the living conditions of the common people did not advance from a subsistence economy as Kamrunnesa Islam described of the ancient Bengal.

The British bleeds Bengal

The financial bleeding of Bengal began soon after Plassey as Amartya Sen observed (“Illusions of empire: Amartya Sen on what British rule really did for India”, The Guardian, 29 June, 2021). The annual economic drain from Bengal constituted around 10% of Bengal’s GDP in the 1780s (Mufakharul Islam, cited earlier). When the British inherited Bengal from the Mughals the biggest revenue earning State, accounting for 12% of the world’s GDP (Om Prakash. 2006. “Empire, Mughal”, in John McCusker. ed. History of World Trade Since 1450, pp. 237-240). The revenue of Dhaka alone was Rs1 million rupees in the 18th century (Golam Rabbani. 1997. From Mughal Outpost to Metropolis, UPL, pp. 14–19).

The financial loot from Bengal contributed to the first Industrial Revolution in Britain (particularly in textile manufacture) while deindustrializing Bengal. The loot benefited not only the British company officials, but also the British ruling class and businesses who had shares in the East India Company.

The early misuse of state power by the East India Company put the economy of Bengal under huge stress, leading to the devastating famine of 1769-1770 in a region that had seen no famine for a very long time. Financial bleeding and exploitation continued during the whole colonial period which ended with another catastrophic man-made famine in 1943, causing three million deaths (Senjuti Mallik. 2023. “Colonial Biopolitics and the Great Bengal Famine of 1943”, GeoJournal, Vol. 88, pp. 3205-3221).

The Report of Law Commission 1839 noted that one in every five people (20%) in Bengal was a slave. There were more slaves in Bengal than anywhere in the region. The Cambridge Economic History of India states that the percentage of slavery was much lower, 5-9%, in the adjoining states to Bengal – Assam, Tripura, etc.

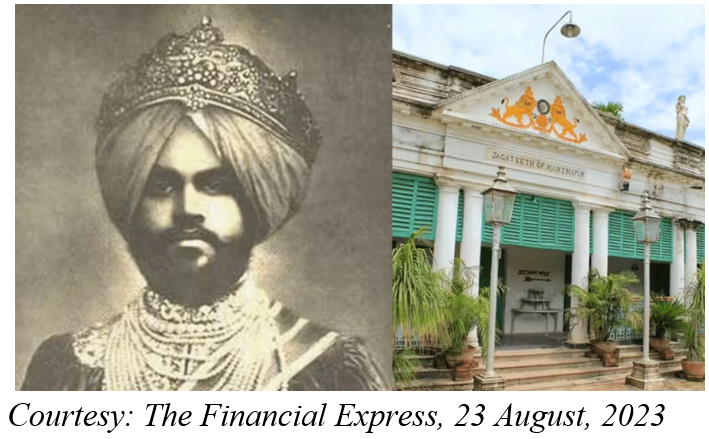

The banker of the world

While the majority of Bengalis had a subsistence living, a few had very luxurious lives. They controlled the economy and wealth was concentrated with them. The most prominent among the few rich was Hirand Sahu. His control of the financial sector of the country earned him the title, “Jagat Seth” – the banker of the world.

The house of Jagat Seth was compared with the Bank of England as the East India Company used Jagat Seth’s credit facilities. Between 1718 and 1730, the imperialist company borrowed, on average, Rs 400,000 annually from Jagat Seth, as mentioned by William Dalrymple in his book The Anarchy.

The house of Jagat Seth was compared with the Bank of England as the East India Company used Jagat Seth’s credit facilities. Between 1718 and 1730, the imperialist company borrowed, on average, Rs 400,000 annually from Jagat Seth, as mentioned by William Dalrymple in his book The Anarchy.

Politics of Tagore’s myth

In 1905 when the British partitioned Bengal along a communal line – East Bengal and Assam (predominantly Muslims) and West Bengal (predominantly Hindus), the well-established Bengali middle-class Hindus popularly called “Bhaddarlok” protested against it violently, while the emerging Bengali middle-class Muslims silently supported it. Thus, the secular Bengali nationalism which flourished in Bengal for centuries was cleft into two antagonistic nationalisms: the Hindu Bengali nationalism and the Muslim Bengali nationalism.

As Mohammad Shihab Khan noted, “The protest against Bengal-partition was electrified with Hindu religious fervour. The ‘Bhaddarlok’ Hindus regarded United Bengal as indivisible as their goddess Kali, and hence partition of Bengal torn her apart” (Mohammad Shihab Khan. 2021. Political Myth of ‘Shonar Bangla’ and Rising Frustration in Bangladesh. Asian Journal of Social Science Studies; Vol. 6, No. 1, pp. 31-48).

Tagore composed multiple songs in protest against the Bengal partition, and perhaps the most famous was “Amar Shonar Bangla”. It depicts Bengal as a peaceful, tranquil and harmonious land; a land which is blessed with endless bounties and captivating beauty; and a land where people and nature coexist amicably.

Thus, “Shonar Bangla” became a myth to the middle-class Hindus; but not so for Bengali Muslims during the anti-British movement. Ironically, the middle-class West Bengal Hindus opted to split United Bengal to form Hindu-dominant West Bengal and Muslim-dominant East Bengal following Hindu-Muslim riots around the mid-1940s while a Muslim leader, Shaheed Suhrawardy (the Premier of Bengal) argued strongly for ‘an independent, undivided and sovereign Bengal’ at a press conference in Delhi on 27 April, 1947 (Bidyut Chakrabarty. 1993. The 1947 united Bengal movement: A thesis without a synthesis. The Indian Economic and Social History Review, Vol. 30, No. 4).

It should be noted that Sarat Bose, a prominent Hindu leader, almost simultaneously argued for a Sovereign Socialist Republic of Bengal. Both Suhrawardy and Bose received support from prominent Muslim and Muslim leaders, such as Abul Hashim and Kiran Sarkar Roy. However, that was not enough to persuade the middle-class Hindu ‘Bhaddarloks’ who wanted to split Bengal along a communal line.

Thus, with the partition of Bengal, Tagore’s “Shonar Bangla” myth was reduced to ashes. But the mythical “Shonar Bangla” saw a phoenix re-birth in East Pakistan. Bengalis demanding their language and political rights and protesting against the Pakistani oppressive regime used “Shonar Bangla” slogan to rekindle secular nationalistic spirit among Bengalis.

The Awami League (AL)’s 6-point charter aimed to transform “Kangal Bangla” into “Shonar Bangla” (destitute Bengal into golden Bengal). The AL circulated a poster with the heading: “Why is Shonar Bangla a crematorium?” (Shonar Bangla Shashan keno?) during the 1970 election. The “Shonar Bangla” myth worked like a silver bullet and helped the AL win a landslide victory in East Pakistan. The prestigious Time magazine headlined Pakistan army’s activities during 1971, “The Ravaging of Golden Bengal”.

Postscript

Turning the country into a “Shonar Bangla” remains an avowed aim; but never explained what it means. A prosperous “Shonar Bangla” never existed, except perhaps during the indigenous Pala dynastic rule over the 756-1143 AD period, which Kamrunnesa Islam described as “self-sufficient”.

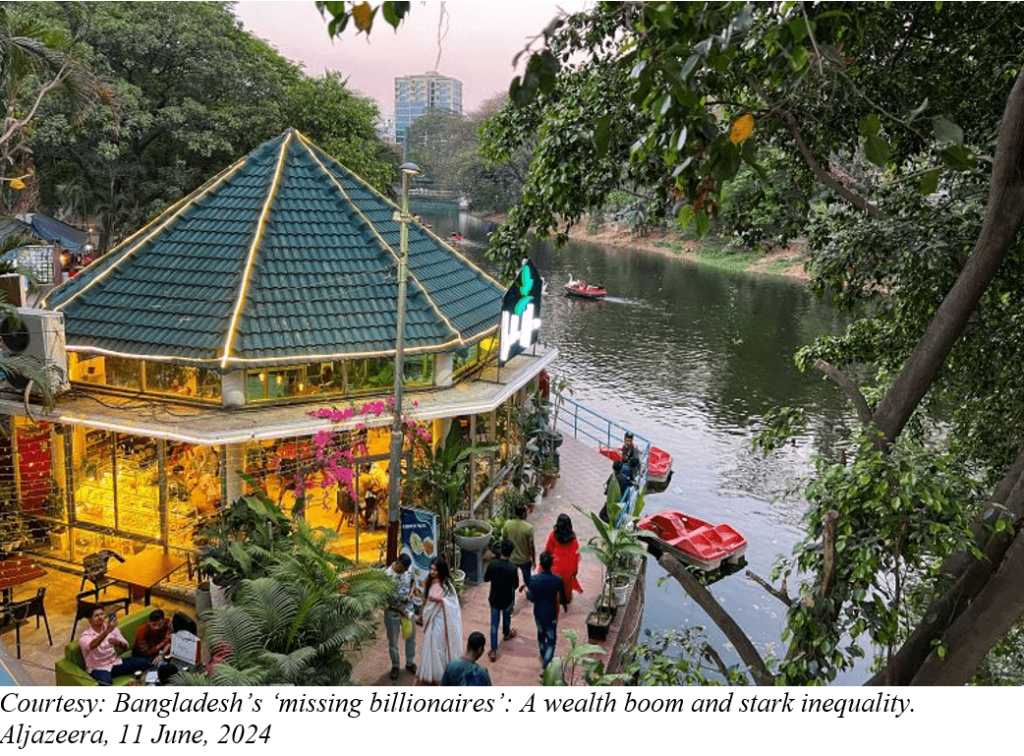

What did exist was a resourceful country supporting an affluent class, where the great majority was struggling to survive. That remains the case even today. Bangladesh is one of the fasted growing economies in the world. It is set to graduate from the least developed status and is now a middle-income country. Its per capita GDP surpassed that of India and Pakistan.

It has also recorded fasted growth of super-rich. According to Wealth-X, Bangladesh saw its ultra-rich club expand by 17.3% between 2012 and 2017. The wealthiest 10% of the population in Bangladesh controls a disproportionate 41% of the nation’s total income, while the bottom 10% receives a paltry 1.31%, according to recent official data. This is the picture of fast-growing Bangladesh, with a growing divide between rich and poor.

Thus, it seems, the reality of a mythical “Shonar Bangla” is persistent poverty and destitution of a great majority amidst growing affluence of a super minority, connected with power, who drains nearly US$3.15 billion annually from the country.

Nevertheless, the people of Bangladesh continue to dream of a prosperous, inclusive and exploitation free democratic Bangladesh.

Anis (Anisuzzaman) Chowdhury, an alumnus of Jahangirnar University and University of Manitoba, is a macro-development economist with close to 100 publications in international journals and two dozen books, including Moulana Bhashani: Leader of the Toiling Masses and Moulana Bhashani: his Creed and Politics. Currently an adjunct professor, he was a professor of economics (2001-2008), Western Sydney University. He served as Director of Economic and Statistics Divisions of UN-ESCAP (Bangkok, 2012-2015) and retired from the UN Headquarters (New York) in 2016 after serving as Chief in the Financing for Development Office. He regularly writes opinion pieces on global socio-economic-political issues. He serves on the editorial boards of several academic journals.