Chattagram is well known for its revolutionary legacy, ever since the armed uprising, led by Master-da Surjya Sen, against British colonial rule. It continued to play a leading role in the struggle for people’s emancipation from oppressive regimes.

It should therefore not be a surprise that the first formal declaration of Bangladesh’s independence was made from Chattagram. A good and accurate account of the events in March, 1971, leading to the declaration of independence from the Kalurghat radio station, can be found in Major Rafiqul Islam’s লক্ষ প্রাণের বিনিময়ে (1st edition) for the readers seeking a true history.

The history of our glorious liberation war is these days increasingly distorted with politically-motivated, often perverse and malicious narrations. Here I present some of the events – largely under-reported – during the roaring days of March that I can still recall from my fading memory.

The history of our glorious liberation war is these days increasingly distorted with politically-motivated, often perverse and malicious narrations. Here I present some of the events – largely under-reported – during the roaring days of March that I can still recall from my fading memory.

Leadership vacuum

With the sudden death of MA Aziz, one of the most prominent leaders of the Awami League (AL) on January 11, 1971, there manifested a huge vacuum in the AL leadership. MA Aziz was the General Secretary of Chattagram District AL. He was elected as a Member of the National Assembly in the 1970 elections from the heart of Chattagram. As far as I recall, he received the highest number of votes in the entire Chattagram Division, a testimony to his popularity and leadership stature.

The next senior-most AL leader in Chattagram was Zahur Ahmed Chowdhury. He was the President of the Chattagram City AL, and was elected as a Member of the Provincial Assembly. Being a seasoned political leader, Zahur Ahmed Chowdhury should have filled the gap that MA Aziz’s sudden death created.

However, that did not happen. Unfortunately, there were ongoing differences and rivalries between the district and city AL leaderships, and people looked at these two leaders as rivals. Moreover, Zahur Ahmed Chowdhury was mostly involved with labour movements, and hence did not have as wide an influence over the larger political movements in Chattagram as had MA Aziz.

MA Hannan, who was the Organizing Secretary of the Chattagram District AL, assumed the responsibility of Acting General Secretary. However, personality-wise and in terms of influence among the rank and file of the Party, MA Hannan was not a match of MA Aziz. Moreover, not being a born Chittagonian, he lacked some of the legitimacy to be a natural leader of Chittagong. Thus, a huge void within the Chattagram AL leadership remained.

In this leadership vacuum, there was therefore no proper preparation for an impending liberation war. The Chattagram AL leadership could not provide any direction to the restless people. As a result, the situation was moving fast towards chaos, as demonstrated by the Biahari-Bangalee riots and revenge killings of innocent Kabuliwallas – the people from Afghanistan and the Frontier Province of Pakistan – also known as Pathans.

Vengeance and civil strife

Tensions were running high in Chattagram even before Bangabandhu’s historic March 7 speech. A riot broke out between Urdu-speaking Biharis and Bangalees at Pahartali on March 3, following the rumour of the kidnapping and killing of Banglaees by pro-Pakistani Biharis.

Hundreds of youths wielding wood planks, bamboo and sticks marched towards the Railway Wireless Colony in Pahartali, where the incident took place, shouting anti-Pakistan, anti-Bihari slogans.

The area soon turned into a battleground: the Biharis opened fire and the Pakistani Army joans (soldiers) stationed there sided with the Biharis. Many were killed and injured in the March 3 and 4 riots in the Pahartali and Ambagan areas where the Biharis lived in Railway Colonies.

Unscrupulous people also took advantage of the general lawlessness and anger against non-Bangalee communities, deemed pro-Pakistani, to settle their personal issues. The Pathans or Kabuliwallas, who were mainly engaged in money-lending business became the victims. For the dishonest people who borrowed from the Kabuliwallas, the chaotic situation was an ideal opportunity to portray them as enemies or agents of Pakistan. Thus, they became a target of angry directionless people.

Lack of cohesion and preparedness

The situation was not very different for other major political parties, such as the National Awami Party (NAP), both pro-Beijing Bhashani and pro-Moscow Muzaffar groups, and various factions of the left political parties. While the pro-Moscow NAP was simply toeing the AL line, the Bhashani NAP lacked internal cohesion due to ideological splits among pro-Beijing left politicians within as well as its 1970 election boycott.

The only exception was a small pro-Beijing group belonging to the faction led by Kazi Zafar Ahmad. The student wing of this group called for armed struggle to establish Shadhin Janaganatanthric Purba Bangla (Independent People’s Democratic Republic of East Bengal) on February 22, 1970, after a mammoth public meeting at the historic Paltan Maidan (Dhaka).

Kazi Zafar, Rashed Khan Menon and others, including Abdullah Al Noman and Kazi Siraj of Chattagram, were sentenced to various terms in absentia by the Military Government of Yahya Khan for their open call for an armed struggle. Only Mahbullah was arrested and put in jail, while the rest went underground and prepared for the impending armed struggle.

Despite the senior leadership (Abdullah Al Noman and Kazi Siraj) going into hiding, the activists belonging to this group regularly brought out processions demanding the independence of East Bengal and calling to take up arms. Their key slogan was, Krishak-Sramik Austra Dharo, Purba Bangla Shadhin Karo (Peasants-Workers take arms, make East Bengal independent).

Moulana Bhashani comes to Chattagram

Moulana Bhashani announced his tour of Chattagram, which involved a public meeting on March 19 at the Laldighee Maidan. Naturally, there was a lot of excitement and suspense about this visit. The restive people of Chattagram were eager to hear instructions and an action programme for independence from this great leader.

While there was confusion arising from Bangabondhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman’s March 7 speech – whether he has actually declared independence – and the lack of transparency in his negotiations with Gen. Yahyah or discussions with Bhutto, Bhashani’s stance was clear. On January 7, 1971, he announced a 5-point programme of action for independence and a sovereign East Bengal, and on March 9 – 2 days after Bangabandhu’s historic speech – Bhashani declared the independence of East Bengal at a huge meeting at the Paltan Maidan.

Moulana Bhashani was well known for sowing the seeds of independence in 1957 when he warned the Pakistani ruling class that East Bengal would be forced to say “আসসালামু আলাইকুম” (good-bye) to Pakistan if the heavy-handed treatment of the Eastern wing of the country continued and the legitimate demands and grievances of the people of East Bengal were not met.

Moulana Bhashani declared his one-point demand of East Pakistan’s independence on November 23, 1970 during a mammoth public meeting at the Paltan Maidan, following his visit of the coastal areas and islands devasted by one of the world’s worst cyclones, which killed over half a million people. He could not hold his anger at the indifference of the Pakistani rulers to the plight of the cyclone-affected people, and declared, “From today my East Bengal is independent”. The event inspired Poet Shamsur Rahman to pen one of his signature poems, Shafet Punjabi named after the garment that the Moulana used to wear. Bhashani also boycotted the 1970 general elections under the military government of Yahyah.

The organizers completely failed to assess the people’s enthusiasm; on the day of the meeting, streams of people descended to the city’s Laldighee Maidan. The place was packed and there was no space to move; the crowd overflowed more than a mile in all directions, chanting and roaring slogans for independence.

Just before the arrival of Moulana Bhashani at the venue, the pandal collapsed due to the pressure of the people around it. People became agitated as they could not hear their great leader. The organizers quickly announced that the meeting would take place following day, on March 20, at the Railway Polo Ground, a much bigger venue.

On the morning of March 20, Bhashani held a press conference. He demanded that Gen. Yahyah form an interim government with Sheikh Mujib as chief to guide the process of the peaceful independence of East Pakistan and to decide the relations between Pakistan and an independent East Bengal.

The failure to anticipate the people’s aspiration for independence was reflected in the chaos among the rank and file within the Bhashani NAP as mentioned earlier. To make the situation worse, the NAP (Muzaffar) failed to unite; instead, the activists of its student wing were holding its conference on the same day in the city’s J.M Sen Hall. There were also skirmishes between them and the activists of the Zafar-Menon group who gathered outside the J.M. Sen Hall for their procession to Bhashani’s Laldighee Maidan meeting.

Preparing for armed struggle

The activists of the Kazi Zafar-led group were engaged in collecting chemicals for making bombs. They planned to break into the Chemistry Laboratory of the Chittagong Government College. Their first attempt on the night of March 11 failed, and they planned to try again on March 13.

On March 12 Kazi Zafar Ahmad came incognito to Chattagram in the car belonging to the famous filmmaker, Zahir Raihan, to see for himself the preparation for an armed struggle. He offered to lead the Chittagong College Chemistry Laboratory raid on March 13. The raid was successful; the chemical containers were loaded into Zahir Raihan’s car and taken to hiding places, which included the village home of Abdullah Al Noman in Gahira.

A group of second-tier AL leaders, e.g., eye-specialist Dr. Abu Zafar, Abdullah Al Harun, MA Mannan (City AL General Secretary), Dr. Foyez Ahmed; and Student League (SL) leaders, e.g., Abdur Rouf (who was VP of the Chittagong Government College Student Union), also anticipated the situation and began collecting arms and ammunitions. This included lootings of a number of gun shops and warehouses in the town. One of them was in Anderkilla, housed on the ground floor of the district AL office.

Bombing campaigns

The activists of the Zafar-Menon group immediately engaged in making bombs and molotov cocktails with the raided chemicals. Their bombing campaign began with attacks on the premises of the Daud Corporation, Amin Jute Mills and the American Cultural Centre, seen as symbols of the Pakistan regime and its international backers.

Although these were just sporadic events, they created a lot of excitement among the restive people of Chattagram who were looking for some direction. They could understand what was coming, and see some preparations were in process in the midst of the chaos and leadership vacuum.

A good account of the operations of this group can be found in Mridul Guha’s Mukti Judde Bam Dhara. Mridul was directly involved, and listed the names of student activists who participated in these operations.

A good account of the operations of this group can be found in Mridul Guha’s Mukti Judde Bam Dhara. Mridul was directly involved, and listed the names of student activists who participated in these operations.

Cultural front

In the AL leadership vacuum, some left-leaning intellectuals and cultural activists played a critical role in organizing and motivating the people for the final struggle for independence. The leading personalities among them were Abul Fazal, playwright and dramatist Professor Momtazuddin Ahmed, Dr. Kamal Khan (Chief Medical Officer, Chittagong Port Trust), Mahbub Hasan, Rashid Chowdhury, Devdash Chakkravarti, Saleha Chakkravarti, Dr. Abu Zafar (eye specialist), Christopher Rozario, Salma Khan. They formed the “Artistes-Litterateur Cultural Enthusiasts Resistance Platform” to spread the nationalist spirit among the Bangalees through cultural programmes.

The Resistance Platform organized a public meeting on March 15 at the historic Laldighee Maidan, followed by a cultural function of “kobi gans” (poet’s duels) and patriotic songs, ending with a drama, Ebarer Sangram, written and directed by Momtazuddin Ahmed.

The meeting was presided over by the literary personality Abul Fazal. It was a huge gathering of freedom-seeking people from all walks of life. It looked like an ocean of people, way beyond the venue, extending miles in each direction. After the success of the event, the team staged cultural programmes and Ebarer Sangram on trucks at important crossroads throughout the city. Each event drew crowds of huge numbers.

Seeing the success of these cultural events, the Student Union of Chittagong University organized a similar event at a much bigger venue – the Parade Ground of the Chittagong Government College, on March 23. This time, they staged Momtazuddin Ahmed’s Shadinatar Sangram and Kazi Nazrul Islam’s dance-drama (নৃত্য-নাট্য), Bidrohee, performed by the city’s famous dancer, Runu Biswas. Again, thousands of people seeking independence poured onto the Parade Ground, overflowing into the nearby streets.

Seeing the success of these cultural events, the Student Union of Chittagong University organized a similar event at a much bigger venue – the Parade Ground of the Chittagong Government College, on March 23. This time, they staged Momtazuddin Ahmed’s Shadinatar Sangram and Kazi Nazrul Islam’s dance-drama (নৃত্য-নাট্য), Bidrohee, performed by the city’s famous dancer, Runu Biswas. Again, thousands of people seeking independence poured onto the Parade Ground, overflowing into the nearby streets.

Blocking MV Swat

As the people were roused by Shadinatar Sangram and Bidrohee, the news arrived that MV Swat, a Pakistani ship carrying weapons for the occupation forces, had anchored at the Chittagong Port for unloading the following day, March 24. People immediately knew what needed to be done: they proceeded from the Parade Ground towards the Chittagong Port to block Swat’s unloading. They roared the slogan, “Bir Bangalee austra dharo, Bangladesh shadheen karo”.

Many laid down their lives when the Pakistani troops opened fire as the crowd reached the Pakistan Navy’s Chittagong Headquarters in Tiger Pass (past the Polo Ground).

Confusion, fear and gloom

The news of the military crackdown on the night of March 25 came as a complete shock, as the AL leadership was still conveying some hope of a peaceful outcome from the ongoing Yahya-Mujib negotiations. No senior AL figures were seen on the street on March 26, except a few such as Prof. Khaled (MP from Raozan, who defeated Fazlul Qader Chowdhury), Dr. Abu Zafar, Abdullah Al Harun, Sekandar Khan and MA Mannan. The people did not know what to do. There was complete darkness about the fate of their leader, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib.

There was an overwhelming mood of gloom, uncertainty, fear, and preparedness to flee the town. It was heightened by unconfirmed news and rumours of the killings of scores of Bengali soldiers and the arrest of the senior-most Bengali officer in the Chittagong Cantonment, Brigadier Majumder, by the Pakistani Army.

Zia’s firm and assuring voice

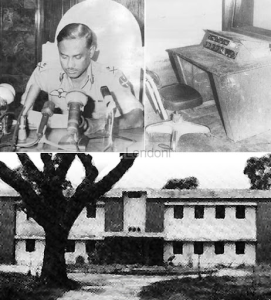

Suddenly, on March 27, on a very faint airwave, came Major Zia’s voice – Ami Major Zia Balchi (I, Major Zia, speaking) – followed by the declaration of a sovereign and independent Bangladesh. “I, Major Zia, do hereby declare independence of Bangladesh.” It was much assuring: a military man was in command.

Suddenly, on March 27, on a very faint airwave, came Major Zia’s voice – Ami Major Zia Balchi (I, Major Zia, speaking) – followed by the declaration of a sovereign and independent Bangladesh. “I, Major Zia, do hereby declare independence of Bangladesh.” It was much assuring: a military man was in command.

However, later, Zia announced: “I, Major Ziaur Rahman, on behalf of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, hereby declare that the independent People’s Republic of Bangladesh has been established. I call upon all Bengalis to rise against the attack by the West Pakistani army. We shall fight to the last to free our motherland”.

There are claims and counter-claims regarding how and why Major Zia amended his initial declaration from his own name to “on behalf of Bangabandhu …” A number of people in their memoirs have claimed credit for it (see The Daily Star, April 7, 2014). Only Belal Mohammad’s narration seems credible; others were simply not in the room.

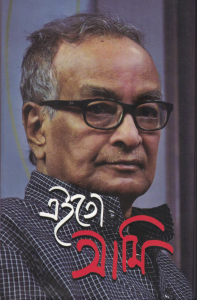

Professor Momtazuddin Ahmed wrote in his memoir, that on March 27 he went to the Kalurghat radio station from where Major Zia read the declaration of independence. He found Major Zia with some Bangalee soldiers, along with a few radio station technicians and personalities, e.g., Belal Mohammad, and student leader Abul Kashem Shandeep, who was Momtazuddin Ahmed’s direct student. They asked Momtazuddin Ahmed to translate Major Zia’s declaration into Bangla; he dictated it to Abdul Kashem Shandeep. On page 158 of his memoir, Momtazuddin Ahmed wrote, “Major Zia read both English and Bangla declarations”.

Professor Momtazuddin Ahmed wrote in his memoir, that on March 27 he went to the Kalurghat radio station from where Major Zia read the declaration of independence. He found Major Zia with some Bangalee soldiers, along with a few radio station technicians and personalities, e.g., Belal Mohammad, and student leader Abul Kashem Shandeep, who was Momtazuddin Ahmed’s direct student. They asked Momtazuddin Ahmed to translate Major Zia’s declaration into Bangla; he dictated it to Abdul Kashem Shandeep. On page 158 of his memoir, Momtazuddin Ahmed wrote, “Major Zia read both English and Bangla declarations”.

And this is what we and others still remember.

MA Hannan’s speech

However, people were still not sure of AL’s stance and did not know about Bangabandhu. It was required to have some senior AL figure to endorse and MA Hannan made a short speech on the evening of March 27, confirming Zia’s declaration of independence on behalf of Bangabandhu and urging the people to unite in the liberation war. Hannan’s speech was retransmitted on March 28.

It appeared a bit strange to many that a senior AL leader like MR Siddiqi, an elected member of the National Assembly (since 1962), who was also the president of Chittagong district unit of AL, treasurer of AL central committee and convenor of Chittagong district Sangram Parishad, did not read the declaration of independence, nor made any speech endorsing Zia.

Equally surprising was the absence of Zahur Ahmed Chowdhury. He was much closer to Bangabandhu, and the one to whom Bangabandhu apparently sent his message, but did not read the declaration of independence. Instead, it was MA Hannan – neither an elected representative, nor as close a confidant of Bangabandhu, and thus with less authority – who was chosen to do the task and made a short speech.

Equally surprising was the absence of Zahur Ahmed Chowdhury. He was much closer to Bangabandhu, and the one to whom Bangabandhu apparently sent his message, but did not read the declaration of independence. Instead, it was MA Hannan – neither an elected representative, nor as close a confidant of Bangabandhu, and thus with less authority – who was chosen to do the task and made a short speech.

I expressed my surprise to Professor Momtazuddin Ahmed on the same evening (March 27). He told me that MA Hannan was the only one whom they could find at that point, as most other senior AL leaders had already gone into hiding.

Reflections

It is reassuring that my recollections of some significant events in Chattagram during the restive March 1971 are supported by recounts of those who were directly involved. I hope this should settle politically-motivated, malign narrations of our glorious history of liberation.

Anis (Anisuzzaman) Chowdhury, an alumnus of Jahangirnar University and University of Manitoba, is a macro-development economist with close to 100 publications in international journals and two dozen books, including Moulana Bhashani: Leader of the Toiling Masses and Moulana Bhashani: his Creed and Politics. Currently an adjunct professor, he was a professor of economics (2001-2008), Western Sydney University. He served as Director of Economic and Statistics Divisions of UN-ESCAP (Bangkok, 2012-2015) and retired from the UN Headquarters (New York) in 2016 after serving as Chief in the Financing for Development Office. He regularly writes opinion pieces on global socio-economic-political issues. He serves on the editorial boards of several academic journals.