The liberation of a nation is a continuous process; it does not happen on the spur of a moment. Our liberation struggle began much earlier than on 26 March 1971, when it took a definitive turn.

The aspiration of Bangalees to be a free nation did not die at the Plassey in 1757; the fire continued to smoulder, at times flaming into armed struggles, such as the Narkelberia Peasant Uprising in 1831 organized by Titu Mir and the 1930 Chittagong armoury raid led by Master-da Surya Sen.

The Bangalee aspiration of liberation transcends religion, though at times religion appeared to divide the nation. Thus, we find nationalist leaders, like MN Roy, CR Das, Subash Bose, AK Fazlul Huq, Huseyn Shaheed Suhrawardy and Moulana Bhashani, adorned by the larger community, while both Rabindranath Tagore and Kazi Nazrul belong to the whole nation. The language and shared history have bound the nation together.

The struggle for economic and national emancipation

Being disappointed with the demise of short-lived hope for a united free Bengal due to the opposition of the Congress, dominated by Hindu nationalists and betrayed by the non-Bengali Muslim League elites’ reinterpretation of the Lahore Resolution, Bangalees were vigilant against mischievous attempts of subjugating the nation. They immediately recognized the ill motive when Mr. Jinnah insisted on making Urdu as the only state language of Pakistan.

Although Tamaddun Majslish, a literary and cultural organisation, led by Principal Abul Kashem, first demanded Bengali to be a state language shortly after Pakistan was created in 1947, the left-leaning progressive students and political leaders increasingly became critical in advancing the cause. They widen the language movement into the struggle for economic and national emancipation beyond mere symbolism.

On 6 March, 1948, the East Bengal Organising Committee of the Communist Party of Pakistan took to the streets with the slogan “laakho insaan bhukha haye, yeh azadi jhoota hain; saacchey azadi chhinkey lao” (hundreds of thousands of people are hungry, this freedom is a hoax, let’s snatch away real freedom). The disillusioned workers in East Bengal, led by communists, staged 26 strikes and walkouts between 14 August and 31 December, 1947, with more than 12,000 workers participating. In 1948, Dhaka University employees went on a two-and-a-half-month-long strike joined by students. A total of 255 strikes and walkouts took place during 1948-53 with 132,843 participating workers. They were mostly organized by the communists, despite crack-down on them.

Meanwhile, peasants were organized across the country breaking through communal lines and uniting adibashi (indigenous people), Hindu, and Muslim peasants. A peasant rebellion in March 1948 around Nachol thana by well-organized Hindu, Muslim and Saontal peasants under the leadership of Saontal leader, Matla Sardar, and communist leaders Ramen and Ila Mitra took the jotdars and zamindar by surprise. In a matter of few months, the Tebhaga policy that reduced the amount of crops to be paid as tax from a half to one-third of the harvest was applied throughout the Nawabganj district, even though the rebellion was brutally crushed and Ila Mitra was subjected to inhuman torture.

Another landmark was the armed conflict, organized by communist and adibashi leadership, between Hajongs (indigenous people in the Garo Hills of the Mymensingh district) and the government during 1949-50 seeking the abolition of the Tanka policy. Under this policy, zamindars (landlords) decided the amount of tax to be paid in crops, which remain fixed regardless of production and increased annually, thus binding the peasants into transgenerational debt.

Despite the martyrdom of 40 sleeping unarmed Jagoripara villagers in Kalmakanda and the arrests of 50 peasant activists, Hajongs remained resolute, taking up the slogan “jaan debo tobu bhaat debo na” (Would rather give my life than my food). And in the mid-1950s, Chief Minister Nurul Amin declared the abolition of the Thanka policy. But soon the government began its vicious displacement campaign against the Hajongs, driving most of them away to Assam and Meghalaya in India. Communist leaders were either imprisoned or had to escape to India.

In the face of brutal crack-downs, the East Bengal Organising Committee of the Communist Party decided in the mid-1950s to focus their efforts on the nascent Language Movement. They formed Jubo League, a mass organisation, in April 1951 in collaboration with liberal groups. The Jubo League activists served as vanguards of the demonstrations, leading up to 21 February, 1952 and beyond.

The Language Movement was taken forward by Moulana Bhashani. On 31 January 1952 Bhashani formed the All-Party Language Movement Committee, and the communists decided to work under the shelter of Moulana Bhashani when the party was banned in 1954. Bhashani’s anti-imperialist and anti-feudal politics resonated with the communists, while Bhashani was impressed by their dedication and struggle for economic and social justice. Thus, it seemed a natural alliance in the struggle for national and economic emancipation.

From Kagmari to the 1969 mass uprising

The historic Kagmari conference in 1957 of the Awami League (AL) was a defining moment in the history of our liberation movement. Moulana Bhashani, the Founding President of the AL, warned West Pakistani ruling class that the people of East Bengal will be forced to say  Assalaamualaikum (bid farewell) to Pakistan. He demanded full autonomy for East Pakistan with only defence, foreign policy and finance (currency) portfolios at the centre.

Assalaamualaikum (bid farewell) to Pakistan. He demanded full autonomy for East Pakistan with only defence, foreign policy and finance (currency) portfolios at the centre.

Ironically, the Prime Minister of Pakistan HS Suhrawardy of the AL back-tracked from the party manifesto of full autonomy and non-aligned foreign policy. This ultimately caused AL’s split. Moulana Bhashani formed a new progressive political party, the National Awami Party (NAP), with the Left progressive forces within the AL to advance the cause of self-determination and to establish an exploitation free country.

The student wing of the NAP, East Pakistan Student Union (EPSU), played a critical role in the first open protest in 1962 against the military rule of Field Marshall Ayub Khan. The movement is popularly known as “1962 Education Movement”, which culminated on 17th September 1962.

Through this movement a group of talented progressive student leaders emerged; notable among them were Kazi Zafar Ahmad, Mohiuddin Ahmed, Rashed Khan Menon, Haider Akbar Khan Rono, Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan, Mostafa Jamal Haider, Ayub Reza Chowdhury and Reza Ali. They played a pivotal role in the 1969 mass uprising. As a member of the organising committee of the All-Party Student Movement, Mostafa Jamal Haider was one of the architects of the 11-points demand.

The student movement turned into a mass uprising against the Ayub regime with the martyrdom of student leader Asaduzzaman who belonged to the EPSU (Menon). Asad’s blood-soaked shirt which became a symbol of resistance was carried on a bamboo pole by Nazma Shika, also belonging to the EPSU (Menon).

In April, 1969, the Left movement, known as the Co-ordinating Committee of the Communist Revolutionary of East Bengal (CCCREB) led by Kazi Zafar Ahmad drafted the programme for an Independent People’s Democratic East Bengal. The programme not only called for an armed struggle, but also contained in 20 chapters with sub-sections detailed outlines of political, economic and social systems of the Independent People’s Democratic East Bengal.

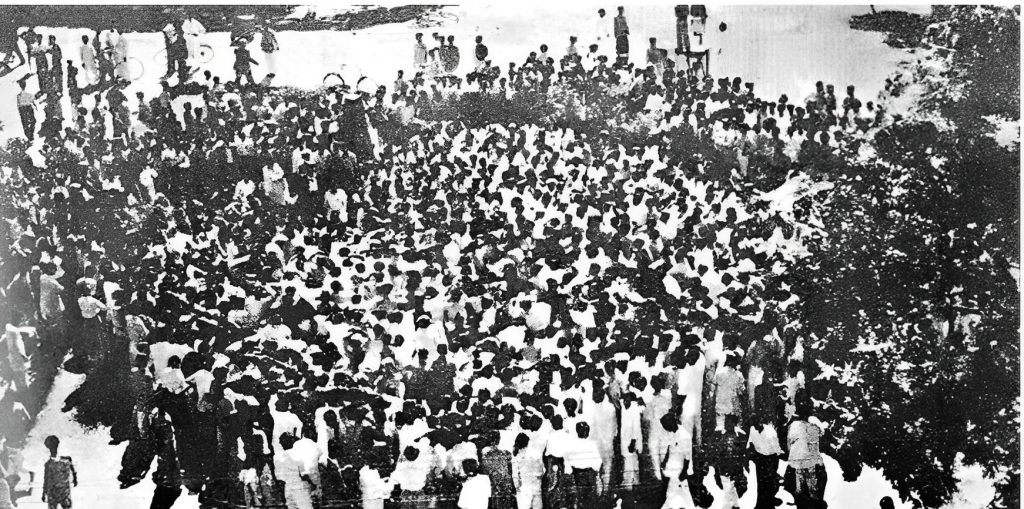

On 22 February, 1970, the programme was openly presented to the people from a mammoth public meeting at the historic Paltan Maidan, organized by the EPSU (Menon). Mostafa Jamal Haider presided over the meeting and Atiqur Rahman Salu, the organising secretary of EPSU (Menon), presented the programme. These courageous and visionary progressive leaders came under heavy criticisms from mainstream political parties, such as the AL and the pro-Moscow NAP; and national dailies, such as the Ittefaque of the AL urged the military government exemplary punishments for these “reckless radicals”.

They were tried in absentia; Kazi Zafar Ahmad and Rashed Khan Menon were sentenced 7 years rigorous jail term and confiscation of half of their properties. Mostafa Jamal Haider, Mahbubullah (General Secretary, EPSU-Menon) were given one-year jail term. Arrest warrants were issued against Atiqur Rahman Salu. Abdullah al-Noman and Kazi Siraj were also given one-year imprisonment for organising meetings and processions in Chittagong in support of the programme. While Mahbubullah was arrested, others went underground, and continued to organize the armed liberation struggle.

From elections to the black night

The Left movement, led by Kazi Zafar Ahmad rejected the general elections, announced by the military Government of Gen. Yahyah Khan. They raised the slogan “Krishak-sramik-chatra-janata oustra dhoro, Purba Bangla Shadhin karo” (Peasant-workers-students-people, take up  arms and liberate East Bengal). While they were preparing the people for an armed struggle, the mainstream parties, including the pro-Moscow NAP, were busy with elections.

arms and liberate East Bengal). While they were preparing the people for an armed struggle, the mainstream parties, including the pro-Moscow NAP, were busy with elections.

Moulana Bhashani, too, boycotted the elections, disappointing the liberals within his NAP. He raised the slogan, “Voter baxe lathi maro, Purba Bangla Shdhin karo” (kick away the ballot box, make East Bengal independent).

Various pro-Peking communist party factions also rejected elections; however, they could not agree on the main issue of national liberation versus the annihilation of class enemies, such as the landlords and the super-rich. It was really ironic because these pro-Peking communists had programmes for the liberation of East Bengal and people’s democratic revolution from the mid-1960s.

Meanwhile, on 12 November 1970, the country was struck by one of the deadliest cyclones in history, causing enormous damages and more than half a million deaths. There was a complete neglect of the plight of the people by the West Pakistani ruling elites. After returning from the tour of the devasted coastal areas, Bhashani formally bade good-bye to West Pakistan on 30 November 1970 from a huge public meeting at the Paltan Maidan, saying that the utter indifference of West Pakistani elites towards the wellbeing of Bangalees had vindicated his warning 13 years ago. Therefore, he put forward his One-point demand for full independence of East Pakistan and called on the people to join the national liberation struggle and boycott the election.

On 9 January 1971, Bhashani organized an All-party conference in Santosh demanding no compromise and the establishment of an independent East Pakistan based on the historic Lahore Resolution. The conference adopted a 14-points programme of action towards achieving the goal. Bhashani presented the 14-point programme on 9 March from a mammoth meeting at the Paltan Maidan, a day after Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujib ended his historic speech saying, this struggle was for our liberation, but falling short of outright declaration of independence. Bhashani warned Sheikh Mujib against any compromise and said that people would never accept anything less than full independence. He reiterated his demand from a huge public meeting in Chittagong on 17 March.

On 25 March, 1971, Bangla Sramik Federation and Purba Bangla Biplobi Chatra Union jointly held a huge public meeting at the historic Paltan Maidan. Kazi Zafar, Rashed Khan Menon and Atiqur Rahman Salu addressed the meeting and called upon the people to take up arms warning that an attack by Pakistani army was imminent. Meanwhile, the Left group, led by Kazi Zafar Ahmad, began organising for the liberation war, and setting up guerrilla warfare training centres in different parts of the country with headquarters in Shibpur under the command of Abdul Mannan Bhuiyan.

After the meeting they led a huge procession to the Shaheed Minar to take their solemn oath to liberate East Bengal. The party activists were asked to go to their respective areas and villages to organize the people, and receive arms training. Needless to say, it was the last public meeting in East Pakistan.

Efforts for a unified war of liberation

As mentioned earlier, the pro-Peking Left parties were divided on the question of main enemy; however, after the military offensive against the Bengali people, it became clear who the chief enemy was. Therefore, Kazi Zafar Ahmad led CCCREB and Deben Shikdar led the Communist Party of East Bengal took initiatives to unite various Left groups for the national liberation war. They met at a conference on 1 and 2 June in North Beleghata of Kolkata and formed Coordinating Committee for National Liberation with Moulana Bhashani as the Chairman. The famous left leader, Sri Baroda Bhushan Chakravarty of Dinajpur, presided over the conference.

Bhashani could not attend the conference. His letter of support was read out where he indicated that he had difficulties in attending, but was well. He advised the Left forces to work jointly with the AL, which was endorsed by the Conference.

Unfortunately, the AL-led Provisional Government did not receive this initiative positively. The Indian government was also suspicious; it did not want a Left-influenced independent Bangladesh to emerge as its neighbour.

Nevertheless, the Left parties continued their efforts in various parts of the country, and many of them fought valiantly, often side-by-side with the Mukti Bahani.

Qualitatively different

The above account of the long process and dynamics of our liberation shows that the progressive Left forces played significant roles and their participation has been qualitatively different from others. They had a clear vision and they fought for an ideal unlike those who joined the war reactively without any preparations. To them political freedom would be hollow without economic emancipation of the nation and the down-trodden.

Thus, even though Bangladesh has emerged as a sovereign country with geographical boundaries, the ideal of the progressive Left still remains unfulfilled. Bangladesh now is one of the few countries in the world characterized by extreme inequality of wealth and income. It recorded the fasted growth rate of super-rich in recent years, while common people are increasingly burdened with debts. It also ranks low in human rights and democratic governance.

Had the AL-led Provisional Bangladesh Government embraced the offer from the Coordinating Committee for National Liberation of the progressive Left forces to mount a united liberation war, perhaps the outcome would have been qualitatively different. Perhaps, we would not have seen rampant corruptions and abuse of power immediately following the emergence of

Bangladesh as an independent country. Perhaps people would not have become disillusioned so quickly.

Nevertheless, the aspiration for true emancipation lives on. The Left needs to unite for liberating the nation from all forms of injustice, oppression and inequity, and to safeguard its sovereignty from expansionist and imperialist powers.

For more details see, মৃদুল গুহ, মুক্তিযুদ্ধে বামধারা, আলো প্রকাশনী, 2012, and হায়দার আকবর খান রনো (edited), মুক্তিযুদ্ধে বামপন্থীরা, তরফদার প্রকাশনী, 2018

Some excerpts from হায়দার আকবর খান রনো (edited), মুক্তিযুদ্ধে বামপন্থীরা:

Kazi Zafar Ahmad:

The National Coordination Committee for Liberation War was formed in a meeting in June. Deben Sikdar of Purba Bangla Communist Party, Nasim Ali of Bangladesher Communist Party – Haateear group, Amal Sen of Communist Songhatee Kendra, Dr. Saif-ud-Dahar of Communist Karmee Sangha and I from the Co-ordinating Committee of the Communist Revolutionary of East Bengal (CCCREB) were members of the committee. The CCCREB guerrillas, about 10,000, fought in Shibpur, Monohardi, Raipura and Kaliganj, places within dozens of kilometres from Dhaka. The occupying Pakistan army failed to organize any auxiliary force in support of its occupation in this area. Our headquarters was in this area. About 5,000 CCCREB guerrillas operated in the southern part of Cumilla. About 5,000 guerrillas organized by CCCREB joined the liberation force under the leadership of Kader Siddique in Tangail area. In Satkhira area, a force of 2,000 CCCREB guerrillas was organized. About 3,000 CCCREB guerrillas operated in Bagerhat-Bishnupur-Raghunathpur area. A force of about 2,000 CCCREB guerrillas was organized in Atrai, Naogaon. A force of a few hundred CCCREB guerrillas was organized in Boalmari and Madaripur. A few hundred CCCREB guerrillas operated in Chattogram and Raojan area. These guerrillas mainly operated in the city area. In the Feni area, a force of a few hundred guerrillas operated. (“Kazi Zafar Ahmader saakkhaatkaar”, pp. 71-80)

Rashed Khan Menon:

The single uniformity of idea among the squabbling pro-Peking communist factions and sub-factions was: an independent Bangladesh to be achieved through an armed struggle. The slogan that dominated the peasants’ conference at Sahapur, Pabna, in 1968 was Workers and peasants rise up with arms for an independent Bangladesh. Maulana Bhashani convened this conference. Thousands of peasants from all over Bangladesh joined the conference defying prohibitory order issued by the Martial Law authority. East Pakistan Students Union (Menon) and East Pakistan Sramik Federation, student and labour organizations of Co-ordinating Committee of the Communist Revolutionary of East Bengal (CCCREB) issued the call for an Independent, People’s Republic of East Bengal. The call, along with an 11-point programme, was made at a public meeting held in Dhaka city on February 22, 1970. The call was made following CCCREB’s decision. The student and labour organizations were rechristened as Purba Bangla Biplobee Chaatra Union and Purba Bangla Sramik Federation. Immediately after 25 March, 1971, the fateful day the occupying Pakistan army began its genocide in Bangladesh, the CCCREB began organizing armed struggle. The centre of this activity was Shibpur, Narsingdi, a few dozen kilometres from Dhaka. Golam Mostafa Hillol died while collecting arms. He was the first martyr from the rank of the CCCREB. Armed struggle was initiated in Bagerhat by organizing peasant and student members of the peasant and student organizations under the CCCREB. This force in Bagerhat continued armed fight against the occupying Pakistan army. The CCCREB members led seizure of firearms from a local armoury of police in Pirojpur. That was at the formal beginning of the armed struggle. Fazlu led the seizure. He was later captured by the Pakistan army, and brutally murdered. This unit in Pirojpur kept the Pakistan army on its heels throughout the entire period of the armed struggle. Many members of the CCCREB joined armed fights in different areas under a number of sector commanders. Shahidullah Khan Badal played the main role at the training facility for the freedom fighters at Melaghar, Tripura. Most members of the urban guerrilla unit were members of the student wing of the CCCREB. They carried on heroic operations within the Dhaka city. The Platoon paid a heavy price with a number of martyrs, who were brutally tortured, and then, shot or bayoneted dead. I [Menon], on behalf of the CCCREB, assisted our armed fighters in Dinajpur, Rangpur and Rajshahi. In this task of coordinating armed struggle in the northern districts, I had to work in close collaboration with Sector Commanders Wing Commander Bashar and Lieutenant Colonel Kazi Nuruzzaman, Captain Noazesh and Squadron Leader Sadruddin. Mohammad Toaha, a leader of East Pakistan Communist Party (Marxist-Leninist) successfully organized liberated zone in the river shoal areas in Noakhali. Under his leadership, land was redistributed among the landless peasants in the liberated zone. Moreover, he had no skirmish with the freedom fighters operating under the provisional government of Bangladesh. He established contact with the provisional government also. (“Bangladesher saadheenataa o mooktee jooddhe baampantheeder voomeekaa”, pp. 31-41)

Moni Singh:

The CPB, National Awami Party and Bangladesh Students Union [all these had inclination to pre-Gorbachev Moscow] organized a guerrilla force with 5,000 members. They joined the War for Liberation. Moreover, the two political parties and the student organization organized 12,000 youths, and sent them to the Liberation Force under the provisional government of Bangladesh. Thus, for the War for Liberation, these left political parties and student organization organized in total 17,000 young Freedom Fighters. Our guerrilla teams entered all the districts of occupied Bangladesh. These guerrillas conducted actions in Dhaka, Cumilla, Noakhali, Chattogram, Rangpur, and in different parts of the northern Bangladesh. Our comrades died during the war. Comrades staying within occupied Bangladesh built up organizations for the war and helped the guerrillas conduct operations. Our guerrillas sunk a ship at the Chattogram Port. At Betiara on the Dhaka-Chattogram highway, nine members of our guerrillas died in a fight with the occupying Pakistan army. The Pakistan army killed Shahidullah Kaiser, member of our central committee. (“Mooktee jooddha o communist party”, pp. 15-30).

A shorter version, “Our liberation and the left movement” appeared in New Age (Dhaka, 20 March, 2022)

Anis (Anisuzzaman) Chowdhury, an alumnus of Jahangirnar University and University of Manitoba, is a macro-development economist with close to 100 publications in international journals and two dozen books, including Moulana Bhashani: Leader of the Toiling Masses and Moulana Bhashani: his Creed and Politics. Currently an adjunct professor, he was a professor of economics (2001-2008), Western Sydney University. He served as Director of Economic and Statistics Divisions of UN-ESCAP (Bangkok, 2012-2015) and retired from the UN Headquarters (New York) in 2016 after serving as Chief in the Financing for Development Office. He regularly writes opinion pieces on global socio-economic-political issues. He serves on the editorial boards of several academic journals.