Introduction

I came to Canada for graduate studies at the University of Manitoba in Winnipeg in 1981. At that time, there were approximately 15 to 20 families consisting mostly of graduate students and some professionals such as physicians and engineers. After my graduation, I taught in universities in small and mid-sized cities across the country – from Lethbridge in Alberta, to Victoria in B.C., and Fredericton in New Brunswick – until I finally landed on a tenure track position at Simon Fraser University (SFU) in Burnaby, B.C., in 1995. In those days, Bangladeshi communities in Canadian cities were small, but slowly growing. Since Bangladeshis were smaller in numbers, the social networks for many Bangladeshi families involved other diaspora communities from South Asian countries such as India, Sri Lanka, Nepal and Pakistan. In this short essay, I reflect on my experiences as a Bangladeshi-Canadian immigrant and provide a broad narrative on the history of migration and settlements of Bangladeshis in Canada.

Migration Phases and Factors

The migration of Bangladeshis to Canada began in earliest during the latter half of the 20th century. Initially, small numbers of students and professionals arrived in the 1970s and 1980s, seeking higher education and better employment opportunities. As such, the history of settlement of Bangladeshis in Canada is recent, for two inter-related factors that restricted the migration of Bangladeshis until 1971. First, people in erstwhile East Pakistan were deterred to go abroad due to stringent procedures for Bengali speaking East Pakistanis. Further, there was a built-in bias towards selection of West Pakistani academics and officials for overseas training abroad. As a result, East Pakistan remained a ‘backcountry’ without any real exposure to and contacts with outer world.

Second, until 1962, Canada was a country for ‘White only’ with racist and sexist policies that deterred immigration of racialized populations. Canada indeed had in place numerous discriminatory immigration laws and policies. These policies perpetuated racism, gender inequality, and social divisions. The most noteworthy two exclusionary policies were: (i) the entry tax (commonly known as Chinese Exclusion tax or Head tax) on Chinese people that terminated the entry of Chinese from 1885 to 1947; and (ii) the Immigration Act of 1908, known as the Continuous Journey Act, that severely controlled the entry of migrants from the Indian subcontinent. The Act stated to accept people from the then British Colony India if they had travelled non-stop from the originating country, i.e. Indian subcontinent. The Japanese steamship Komagata Maru failed to meet the condition in 1914, and as a result was turned away. This was known as the Komagata Maru incident, where the ship carrying 376 Indian (vastly Sikhs) immigrants was denied entry to Canada at Vancouver port due to the country’s racist immigration laws.

In the later part of 1960s, Canada began to open its doors to racialized people. This openness was influenced by several factors, such as, growth of Canada’s trade relationship with some Asian countries, its role as an effective member of the United Nations, the demand for labour due to the post-war boom, the shortage of supply of labour from European countries. The 1967 Immigration Act of Canada removed overt racial discrimination that was further enhanced by the Immigration Act of 1976.

The independence of Bangladesh in1971 opened doors and opportunities to Bangladeshis to migrate abroad. The influx was partly driven by the Liberation War when many sought refuge to Canada, which soon turned out as a favorite destination to Bangladeshis. The Canadian immigration policies that evolved further effectively impacting the flow of Bangladeshi migrants. In the early years, the focus was on skilled professionals, which attracted many educated Bangladeshis. The introduction of the points-based system in the 1990s facilitated the entry of migrants who were qualified based on their skills, education, and work experience.

Family reunification policies also played a crucial role in increasing the number of Bangladeshi immigrants, allowing settled individuals to bring over relatives. However, the real surge in migration occurred in the 1990s and early 2000s, driven by political instability, economic hardship, and the search for a better quality of life. Many sought asylum and refugee status after fleeing Bangladesh during periods of political instability in the past. The allure of Canada’s reputation as a land of opportunity, with robust healthcare, education, and social services, remains a significant factor even today.

In sum, Bangladeshis migrated to Canada under three broad categories: (i) skilled/independent categories; (ii) the family category; and (iii) the refugee category. In the past twenty-five years, a vast number of undergraduate student population from Bangladesh migrated to study in both public and private universities, and colleges and gradually earned the independent/skilled category. The student-stream has now become a major source, an estimated 3,000 per year, to the independent and skilled category immigrants to Canada.

Population and Settlements

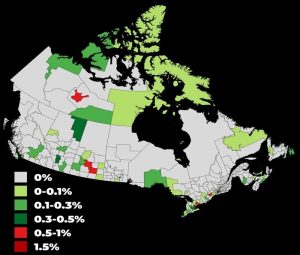

Source: 2021 Census – Distribution of Canadian Bangladeshis across Canada

Source: 2021 Census – Distribution of Canadian Bangladeshis across Canada

The 2021Census reported close to 80,000 people of Bangladesh origin in Canada. Unofficial estimates suggest a population of over 100,000. Bangladeshi immigrants have settled in various parts of Canada, with significant concentrations in urban areas. Toronto, Vancouver, and Montreal are popular destinations due to their diverse communities and economic opportunities. Toronto has the largest Bangladeshi population, with neighborhoods like Danforth Avenue becoming cultural hubs for the community.

Neighborhoods like Danforth and Scarborough have notable Bangladeshis and have grown over the years as vibrant communities. For example, Scarborough Southwest elected Bangladeshi born Doly Begum of the New Democratic Party to the Legislative Assembly of Ontario in 2018 provincial election. She is indeed the first Bangladeshi-Canadian to be elected to a provincial legislature in Canada.

The settlement experience for Bangladeshi immigrants has been marked by both challenges and success stories. Many newcomers initially encountered challenges in adapting to the Canadian climate, language barriers, and cultural differences. However, community organizations (such as, Bangladeshi Cultural Associations) and support networks (such as, Immigrant Settlement Services) have played a pivotal role in helping them navigate these challenges. Social integration has been facilitated through cultural events, religious institutions, and local community centers that offer programs tailored to newcomer needs.

The settlement experience for Bangladeshi immigrants has been marked by both challenges and success stories. Many newcomers initially encountered challenges in adapting to the Canadian climate, language barriers, and cultural differences. However, community organizations (such as, Bangladeshi Cultural Associations) and support networks (such as, Immigrant Settlement Services) have played a pivotal role in helping them navigate these challenges. Social integration has been facilitated through cultural events, religious institutions, and local community centers that offer programs tailored to newcomer needs.

Employment for Bangladeshi immigrants in Canada has been a mixed bag. While some highly skilled professionals have found success in their respective fields – for instance, physicians, engineers, professors etc. – others have faced hurdles such as non-recognition of credentials and fierce competition in their respective job market. Many have had to take up employment below their qualification levels initially, but some have gradually moved up the career ladder through perseverance and additional upgrading of skills and education.

No Reliable Data Across Canada

A vast majority of Bangladeshi immigrants live in Central and Western Canada. Besides Toronto, other major cities – Halifax, Montreal, Ottawa, Winnipeg, Saskatoon, Regina, Edmonton, Calgary, Victoria, and Vancouver have substantial Bangladeshi populations. There are, however, no reliable data on Bangladeshi-Canadian living in these cities or provinces or across the country. For instance, when we moved to Vancouver in 1995, there were not more than 100 people at that time. The Greater Vancouver metropolitan area has now an estimated 15,000 to 17,000 people, according to the Greater Vancouver Bangladesh Cultural Association (GVBCA). The GVBCA celebrates many full-packed cultural events such as Independence Day, Pohela Boisakh, Victory Day, etc. in the city.

As an academic with long-term research trajectory on Asian immigrants in Canada, I always felt constrained to speak about Bangladeshi immigrants in Canada due to lack of any reliable statistics or studies. To fill up this gap, I organized (with Dr. Sanzida Habib as co-organizer) a two-day national conference titled Migration of Bengalis to Canada in 2017 on the eve of Canada’s 150th anniversary.

Canada 150 Conference Proceedings: Migration of Bengalis

Canada 150 Conference Proceedings: Migration of Bengalis

It was funded by the Canadian SSHRC (Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council), with joint sponsorship by the department of Gender, Sexuality, and Women’s Studies (GSWS) at Simon Fraser University and the Centre for India and South Asia Research (CISAR), University of British Columbia (UBC). The focus was on the Bangla speaking population in Canada who migrated from Bangladesh and West Bengal. Bangla as a language binds the Bengalis from both regions despite separate nationalities (i.e., Bangladeshi and Indian). In 2018, the SFU Library published a digitized copy of the conference proceedings for the global readers. The journal Alternate Routes (Vol. 30, No. 1, 2019) published selected articles from the proceedings.

Emerging Issues and Challenges

The Bangladeshi diaspora in Canada is a vibrant and dynamic community that remains to be studied and documented properly. The new immigrants encounter several challenges in their new home. Language proficiency remains a significant barrier, especially for middle-aged and senior immigrants. The integration into the broader Canadian society sometimes conflict with conventional values. Economic challenges, including underemployment and job insecurity, also persist. Discrimination and social exclusion are additional hurdles that many members of the community face.

Further, youth engagement is crucial as the younger generation navigates identity and belonging while balancing traditional values with contemporary Canadian culture. Mental health is another growing concern, with the stress of migration, settlement, financial insecurity, and integration impacting overall well-being. Community leaders are increasingly focusing on these issues through workshops and community-based support groups.

Despite the challenges, the Bangladeshi community has made significant strides in integrating into Canadian society. Education has been a crucial factor, with many second-generation Bangladeshis excelling in academia and entering diverse professional fields. Participation in civic activities and politics is increasingly growing, with members of the community actively engaging in local, provincial, and national matters. Cultural contributions (such as the International Mother Language Day), including the celebration of Bangladeshi festivals (such as, Pitha Utsab), cuisine, and arts, enrich the multicultural tapestry of Canada.

Need for Further Research and Studies

As discussed above, the Canadian journey for the new Bangladeshi immigrants has not been without its challenges. The future of the Bangladeshi diaspora looks promising, representing the true spirit of multiculturalism. However, not much has been written about or published on Bangladeshi diaspora in Canada. There is a need for community/grassroots level research and documentation to further illustrate the contributions as well as challenges encountered the Bangladeshi immigrants across the country. The present author, in spirit of services to the Bangladeshi immigrant communities, has launched an edited book project (with co-editor Mohammad Zaman) tentatively titled Bangladeshi Diaspora in Canada: Exploring History, Settlements and Cultural Integration.

The proposed book project aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the history, profiles, settlement patterns, employment, social/cultural organizations, and identity/languages and the role and contributions of Bangladeshi diaspora (for example, the acclaimed International Mother Language Day) to the Canadian multicultural landscape. The edited book will largely focus on case studies of selected cities (large, medium, and small) – for instance, Montreal, Toronto, Winnipeg, Edmonton, Calgary, Saskatoon, Vancouver, Lethbridge – with a particular attention to (i) early migration patterns and stories; (ii) evolution/demography of the diaspora; (iii) settlement patterns and processes; (iv) employment (all genders) pattern of Bangladeshi-Canadian; (v) economic and social integration; (vi) transforming gender role at the household level; (vii) social

organization, language, and religion; and (vii) cultural identity and interaction with broader Canadian society. The potential contributors include academics, community activists/organizers, independent scholars, writers, and others interested in the documentation of the Bangladeshi diaspora history, settlement patterns, and participation in Canada. The book should be available by end of 2027.

Habiba Zaman

Habiba Zaman is Professor Emeritus at Simon Fraser University. She was also an associate member of SFU Labour Studies Program. Professor Zaman is author of several books, journal articles, reports, and conference proceedings including Asian Immigrants in “Two Canadas”: Racialization, Marginalization, and Deregulated Work (2012; translated in Mandarin, 2021). She is a co-editor of Canada 150 Conference Proceedings on Migration of Bengalis (2018) https://doi.org/10.21810/sfulibrary.73. E-mail: habiba_zaman@sfu.ca