“Won’t you give some bread to get the starving fed? We’ve got to relieve Bangladesh,” sang George Harrison, a former Beatle, in 1971.

In a short span since independence, Bangladesh has proved the sceptics wrong. From an “international basket case” and a “test case of development”, Bangladesh has become an example of success. One leading economic development textbook observed, “And without question, from the viewpoint of the broader meaning of development, Bangladesh seemed to be forging ahead in the early years of the twenty-first century. As a result, there are good reasons to expect Bangladesh to soon move into the lead in income as well” (Todaro and Smith, Economic Development, 2006, p. 89).

Observing Bangladesh’s progress, the UNDP’s 2000 Bangladesh Human Development Report (p. 2), concluded, “It was like a re-birth for Bangladesh, having moved from the status of being at the margin of history in the whirlpool of history, from the status of a mere testing site to that of a learning site…”

A difficult journey

Bangladesh was born as an independent State through the trauma of a brutal liberation war and associated destruction and dislocations. In the aftermath of the Pakistani army’s rampage last March, a special team of inspectors from the World Bank observed that some cities looked “like the morning after a nuclear attack” (BANGLADESH: Mujib’s Road from Prison to Power, Time, 17 January 1972).

One estimate puts the total loss of physical assets to Tk12.6 billion. In the transport sector, about 600 road and railway bridges, and half the trucks and buses were destroyed. Both Chittagong and Chalna ports were heavily damaged and blocked with sunken vessels. About 10 million people fled to India and about 20 million were dislocated internally during the war. The dislocation caused a serious shortage of food, amounting to 3 million tons. Public expenditure on relief, reconstruction and rehabilitation between January 1972 and June 1973 amounted to Tk. 290 crores (US$400 million at the prevailing exchange rate). The economy contracted by about 12% between 1969/70 and 1972/73.

Alas, it was not the best of times – less than two years after its independence, the world economy slipped into a period of prolonged recession and high inflation due to two oil price shocks. The international economic order was also in a disarray, following the unilateral decision of the US to back out from the post WWII Bretton Woods system of gold convertibility of the US dollar at a fixed exchange rate.

Mother Nature was also not kind; a devastating flood hit the country in 1974. The unscrupulous business people and speculators connived with the ruling party’s leaders to take advantage of the situation and caused a famine that killed an estimated 1.5 million (15 lac) people and caused long-term damage to children born during the famine; about 25% of them died before their fifth birthday.

Thus, the task of reconstruction, rehabilitation and development at the dawn of independence was overwhelming. The coups and counter coups and political instability that followed the brutal assassination of the founding father and his family did not help economic management. The country was in a political vacuum with the cold-blooded murder of four senior national leaders in the Dhaka jail. It also lost in the coups and counter coups a number of senior military leaders who were at the forefront of the liberation war.

After the assassination of President Zia, The New York Times (7 June) columnist William Borders asked, “Will Bangladesh make it?” …. if it were a patient hovering between life and death in some intensive care ward. The answer is, of course. The country is not going to disappear and 92 million Bangladeshis, soon to be 100 million, will still be here, whenever anyone cares to look, and still hungry. At times, the signs for them will be a bit better. At other times, they will be a bit worse. Last week they seemed very much worse indeed.”

From despair to hope

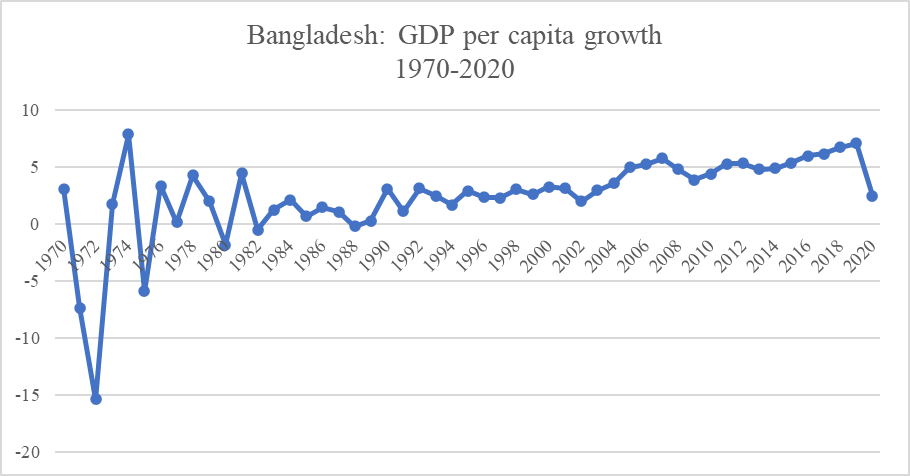

The US Secretaries of State, Henry Kissinger, dubbed Bangladesh an “international basket-case”. In 1976, two World Bank economists, Just Faaland and Jack Parkinson, termed Bangladesh as “the test case for development” – meaning that if development could happen in Bangladesh, it could happen anywhere. Kevin Rafferty of The Financial Times (6 June, 1975) characterised Bangladesh as “the end of the great development dream”. Yet, there were high hopes and great expectations. More significant was the re-generation of hope and creating confidence in the people, especially among the young generation, by President Zia that the doubters could be proved wrong (see The New York Times, “Ziaur Rahman was strict leader who tried to give nation direction”, 31 May; “Remembering Ziaur Rahman, the Leader that “lifted the nation to its feet”, South Asia Journal, 3 June 2021) After a decade of poor performance, the average GDP growth rate accelerated since 2002, reaching over 6% and average inflation rate remained within a single-digit limit. Bangladesh was experiencing nearly 8% GDP growth in recent years, and is one of the fastest-growing economies in the world. Bangladesh’s economy has grown by 188% in size since 2009. Its per capita income reached US$$1,961 in 2020, according to the World Bank, surpassing India’s US$ 1,927 and Pakistan’s US$ 1,189. Bangladesh’s GDP per capita is projected to rise to US$ 4.171 in 2027, according to Statistica.

By the World Bank’s classification of countries, Bangladesh has graduated from “low-income” to “lower middle-income”. Soon it will graduate from the United Nations classification of “least developed country” (LDC) to a “developing” country – a huge advance on the wasteland of 1971.

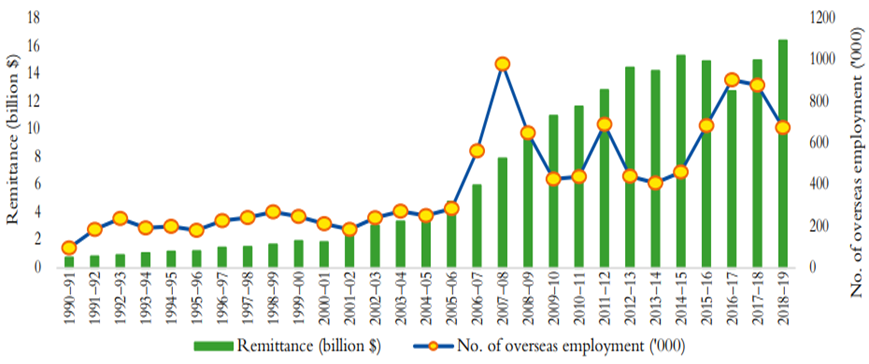

Bangladesh has also made remarkable progress in social and human development. Its Human Development Index (HDI) improved from 0.4 in 1990 to 0.661 in 2021, and life expectancy at birth rose from 47.5 years in 1971 to 72.4 years in 2021. Adult literacy rate jumped from around 30% in 1980 to around 75% in 2020. At 72%, Bangladesh’s female literacy rate is higher than India’s 66% and considerably higher than Pakistan’s 46%. At 26 deaths per 1,000 births, its infant mortality is lower than India’s 28 and Pakistan’s 67. Turning point – key enablers A number of factors contributed to this remarkable turn-around. The first and foremost was the visible improvement in the law-and-order situation during 1976-1980. The second was the emphasis on the rural economy and agriculture with improved irrigation and fertiliser distribution and encouragement of fisheries as well as opening up of new activities such as shrimp culture and poultry. The third was the encouragement of the private sector. Most importantly, during this period the foundation for two critical drivers of the economy – remittances and ready-made garments – was laid.

Although several delegations from the Middle East visited Bangladesh between 1972 and 1975 to recruit workers, no system was in place to promote manpower export in a systemic way. President Zia saw the opportunity and created the Bureau of Manpower, Employment and Training in 1976 to devise policies to export manpower in a coordinated manner. President Zia could also see the opportunity created by quota-free access to the US market of ready-made garments from least developed countries under the Multi Fibre Agreement. His government facilitated technical co-operation and financing arrangements between the Desh Garments and the South Korean Daewoo, under which Daewoo trained Desh Garments’150 personnel in 1979. The government also provided support with back-to-back letters of credit and bonded warehouses that reduced the cost of financing imports of fabric required as inputs.

President Zia also foresaw the demographic shift that was happening in Bangladesh and the growth of young people. Thus, he created special ministry for the development of youth to prevent “demographic curse” and reap “demographic dividend”. These factors and the economic turnaround created hope among the people, especially the young generation – a key for success.

Lest not be complacent

Achieving the middle-income country (MIC) status and LDC graduation have been professed objectives of the Government of Bangladesh; thus, was celebrated with much fan-fare. Certainly, it is a significant achievement for a country, dismissed as a bottomless basket at its birth as an independent State. Let us not turn the rejoice into complacency.

World Bank’s classification of countries by income levels does not reflect broader aspects of development, such as inclusiveness, sustainability or “development as freedom” in the words of A.K. Sen. Its sole purpose is to determine the eligibility of concessional loans. By moving from a low-income country to a MIC, Bangladesh will have to pay market interest rates for its World Bank loans.

On the other hand, LDC status reflect slightly wider dimensions of development. Besides per capita income, it includes two other dimensions: (i) human assets (HA) and (ii) economic and environmental vulnerability (EEV). HA include: (a) nutrition: percentage of population undernourished; (b) mortality rate for children aged five years or under; (c) the gross secondary school enrolment ratio; and (d) adult literacy rate. Thus, HA is almost identical as HDI. As mentioned earlier, Bangladesh made remarkable progress in HD.

However, Bangladesh’s productive capacities remain low. According to the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), “productive capacities are the productive resources, entrepreneurial capabilities and production linkages that together determine the capacity of a country to produce goods and services and enable it to grow and develop.” Bangladesh ranks 140 out of 193 countries in terms of UNCTAD’s productive capacity index, whereas Malaysia ranks 62, Vietnam 99, Sri Lanka 103, India 112, and Indonesia 121. This shows how far Bangladesh has to travel to catch up with its competitors or its ideal Singapore, ranked 13.

EEV relates to: (a) population size; (b) remoteness; (c) merchandise export concentration; (d) share of agriculture, forestry and fisheries in gross domestic product; (e) share of population living in low elevated coastal zones; (f) instability of exports of goods and services; (g) victims of natural disasters; and (h) instability of agricultural production. On a number of these factors, the Bangladesh economy remains extremely vulnerable. For example, Bangladesh’s export base is very narrow, ready-made garments accounting for 83% of total exports in 2020.

Bangladesh also performs very poorly on the environmental front. It ranks162nd out of 180 countries in the 2020 Environmental Performance Index (EPI) of the Yale and Columbia Universities. EPI evaluates the condition of environmental health and vitality of their ecosystems. Bangladesh’s position is the third worst in South Asia with India at 168th and Afghanistan at 178th positions. The EPI evaluates performance across 11 issue categories, such as – environmental health, ecosystem vitality, ecosystem services, fisheries, climate change, and pollution emissions.

Leaving the majority behind

Socialism is a state pillar of Bangladesh; thus, promising shared prosperity for all – “leaving no one behind” for the United Nations Agenda 2030 to which Bangladesh is a signatory.

However, a small section of the society enjoys most of the country’s income and wealth depriving the larger section. The Centre for Policy Dialogue finds that wealth inequality in terms of Gini coefficient stands at a staggering 0.74 on a scale of 0 (complete equality) to 1 (complete inequality). The Bureau of Statistics’ 2016 Household Income and expenditure Survey reveals that the income share of the highest 10% of the household increased from 21% in 1984 to 38.16% in 2016, while the income share of the lowest 10% of the household declined from 4.13% to 1.01%. The Gini coefficient of income inequality reached 0.48, just 0.02 below 0.5 regarded as a red-line.

Oxfam’s inequality report (2018) ranks Bangladesh 148th among 157 countries. Ultra-wealthy people in Bangladesh increased faster than in any other country in the world between 2010 and 2019, finds the latest report of Wealth-X, placing Bangladesh the first among the top 10 fastest growing wealth markets in the world during the period.

The number of wealthy with US$5 million plus in net worth increased by on an average 14.3% per annum in the country. The Credit Suisse Research Institute’s Global Wealth Report-2021 reports 21,399 millionaires in Bangladesh, each owning wealth in the range of US$1-5 million. Bangladesh’s HDI drops from 0.661 to 0.503 when inequality is taken into account.

Democracy deficit

Democracy is another State pillar of Bangladesh; but stands on an unsettled footing. Freedom House describes Bangladesh as “partly free” and gives a score of 39 out of 100, marginally passing. It gets 15 out of 40 in political rights and 24 out of 60 in civil liberties.

Bangladesh ranked 141 on the Human Freedom Index of CATO Institute and Fraser Institute in terms of personal freedom, 133 in terms of economic freedom, and 139 in terms of human freedom out of 162 countries in 2018. Bangladesh was behind Nepal (92), Sri Lanka (94), Bhutan (108) and India (111). Its human freedom index score of 5.67 on a scale of 0 (no freedom) to 10 (more freedom) was below the world average of 6.93.

Global Human Development Report 2000 links development to “Human rights and human development: Any society committed to improving the lives of its people must also be committed to full and equal rights for all”. Unfortunately, Bangladesh has gone backward. Bangladesh’s average score on Human rights and rule of law index, 0 (high) – 10 (low), during the period 2007 – 2022 was 7.2.

High and rising inequality combined with declines in human rights and freedom is a recipe for state fragility. The State Fragility Index 2020 Report of the Fund for Peace ranks Bangladesh 39th among 178 countries with an overall score of 85.7 out of 120. It places Bangladesh in the “High Warning” category.

Democracy vs. development: A false choice

Singapore’s legendary founding leader Lee Kuan Yew promoted the concept of a choice between two D’s: Democracy vs. Discipline. Mr. Lee claimed that countries needed discipline (a code word for repression) more than democracy for accelerating development.

In our historical experience, we have seen Ayub Khan’s “basic” democracy – a form of restrictive democracy touted to be good for development. Ayub Khan celebrated the decade (1958-1968) of development in 1968 under his repressive regime of basic democracy, with GDP growing at 7.3% per annum, exceeding the 5% target of the UN’s First Decade of Development. Thus, Pakistan was seen as a model, many countries seeking to emulate Pakistan’s economic development strategy, including South Korea, Philippines and Indonesia.

Ironically Pakistan exploded before the year of celebration ended; a mass uprising against economic injustice and political repression toppled Ayub the flowing year. In 1970, Pakistan achieved its highest growth rate of 11.4%; yet the country imploded in 1971 with the birth of Bangladesh aspiring for an exploitation free democratic socialist country.

Similarly, three decades (1968-1996) of rapid growth (approximately 7% per annum) under Soeharto could not put out the burning desire of the Indonesian people for democracy. Indoensia suffered the worst of the 1997-1998 Asian financial crisis (AFC) and the regime fell with the implosion of the country that saw the birth of Timor Leste.

Becoming fit through democracy

Those who cite the examples of East and Southeast Asia in advocating repression for the sake of development should know that the constraining of citizen’s participation in ensuring transparency, or the freedom of expression against the concentration of power led to the rise of “crony capitalism”, characterised by corruption of elites connected to power. Many observers believe that the root cause of the AFC was crony capitalism.

Countries that escaped the worst of the AFC or are doing well now are the ones which either had better democratic institutions or undertook radical reform towards democratisation (e.g., Indonesia). South Korea and Taiwan went through this process of democratisation in the late 1980s and early 1990s; thus, they were affected the least by the AFC and recovered quickly. On the other hand, Malaysia, which failed to undertake democratisation reform is mired in political crises one after the other and is caught in what some say is a “middle-income trap”.

We find many more examples of Soeharto or Ayub Khan who introduced various forms of limited democracy in the name of development. Their limited democracies did produce some periods of rapid economic growth; but they collapsed. On the other hand, the probability of finding a Lee Kuan Yew or even Mahathir Mohamad is very small, perhaps one in a thousand.

The beauty of true democracy is that we do not have to search for a Lee Kuan Yew by a rare chance, and get stuck with a bad government in the process; we can replace a bad government with the one that respects human rights, has checks and balance of power and ensures free and fair elections.

Democracy may not produce stellar economic growth rates, but is superior to pseudo democracies in safeguarding stable economic growth by encouraging free thought, experimentation, and innovation without fear or prejudice. It also ensures social justice or equity and environmental sustainability by letting people’s participation in the decision-making process and allowing them to voice their concerns.

Thus, for Amartya Sen, “A country does not have to be deemed fit for democracy; rather, it has to become fit through democracy”. Thus, it is a wrong question to ask whether a country is fit for democracy; instead, a country becomes fit through democracy. Democracy’s appeal does not rest on its instrumental values or its ability to produce high economic growth. Rather, the appeal of democracy is derived from its intrinsic values for human life and well-being, which is facilitated by citizen’s ability to exercise civil and political rights or political and social participation as social beings that in turn ensures Sen’s development as freedom.

Anis (Anisuzzaman) Chowdhury, an alumnus of Jahangirnar University and University of Manitoba, is a macro-development economist with close to 100 publications in international journals and two dozen books, including Moulana Bhashani: Leader of the Toiling Masses and Moulana Bhashani: his Creed and Politics. Currently an adjunct professor, he was a professor of economics (2001-2008), Western Sydney University. He served as Director of Economic and Statistics Divisions of UN-ESCAP (Bangkok, 2012-2015) and retired from the UN Headquarters (New York) in 2016 after serving as Chief in the Financing for Development Office. He regularly writes opinion pieces on global socio-economic-political issues. He serves on the editorial boards of several academic journals.

US secretary of state not secretaries of state was Henry Kissinger. Author should know Kissinger never called BD as a basket case. It was one of his subordinate named Mr. W..

I cannot recall his exact name.