That is the fundamental question that I have asked myself for years, this desire to fit, to be accepted, and considered ‘good enough’. For many diaspora communities, they come to Great Britain in search of that elusive ‘better life’. How can we define ‘better’? Better education, better job, better living conditions, better opportunities? My dream was to be an artist, but I had no idea how to achieve this dream because in the 70s there were no prominent Asian artists to speak of. We never learnt about Tagore at school, and during art history lessons there was no mention of Asian artists. There was a European bias in everything we were taught. And as a Bangladeshi girl, born in Manchester, and growing up in Margaret Thatcher’s Tory Britain how was I going to realise my aspirations?

At school there were not many Asian kids. I recall a girl not wanting to hold my hand fearing my brown colour might indelibly stain her skin. It was habitual, while walking with my sister, to come across white boys who would feign an Indian accent and chant ‘Paki go home’. Witnessing my mother being spat at made me incandescent with rage, but I was too small to fight back. And the rare occasion when we went on holiday in Torquay we were made to sit on our own, separated from the predominantly white guests, while dining. We never questioned the forced segregation. How did these early experiences of racism shape my consciousness? And all the while Margaret Thatcher preached if you work hard you would get ahead.

My father tried hard to assimilate in Britain; he had European girlfriends, wore slick suits, he was worldly and into art and music according to my mother. Initially he had fallen in love with a white woman called Dimna, her parents rejected him; heart broken he returned to Bangladesh in search of a wife. He met my grandfather who gave him permission to glimpse my mother, but not talk to her. But they did talk and within two weeks had a midnight marriage, my mother abandoned her studies at Dhaka University and travelled with him to Bradford. Suddenly she had to learn how to cook and adjust to a radically new life and climate. There was a burgeoning Bangladeshi community in Bradford; my parents were preparing to settle there until my father got a job in a bank in Manchester. When they purchased a house in Fallowfield, we were the only Bangladeshi family on our street. We were considered to be doing well because we had a house with a garden and a car. In old photos my father looked dapper, I often thought he looked like a movie star, how could anyone resist his charms? He enthusiastically went round to all the neighbours, bearing gifts, and was met with hostility. Over time though our neighbours softened and as children we would pop in and out of their houses in search of simple amiable conversation and Murray mint sweets.

When the war broke out between East and West Pakistan in 1971, my father was sacked from the Pakistani bank where he worked. He set up a grocers shop in Rusholme, my mother was sewing and we had lodgers in the house to make ends meet. Money was tight. And then tragedy struck and my father had a double heart attack and died aged 35. My mother was 25 when my father died. I was eight months old; my sisters were aged two and four. The devastation my mother must have felt is hard to fathom. She still sees my father in her dreams. To be an immigrant and a widow in a foreign country was a disaster for my mother. She swiftly remarried my father’s best friend, perhaps out of a need to survive, or was it because they both loved my father? My stepfather often remarked that the death of my father felt like the end of the world. Everything they had known was suddenly shattered.

My mother became a social worker; she had to get two buses to Oldham and would come home exhausted and cranky. In those early years I remember my mother as a volatile, terrifying figure. She would look immaculate and speak softly to strangers and guests but behind closed doors she could explode at the slightest remark. She was unable to achieve the life-work balance. Every penny she earned she spent on our education, for which I am grateful, but she never let us forget this fact. My mother worked tirelessly for the community, setting up a Bangla music and language school to teach us our mother tongue and Bengali folk songs. She helped to bring wives over from Bangladesh to be reunited with their husbands. And she was modern, too, she would wear trousers and even had a perm at one point, but despite her efforts I think my mother still felt a deep sense of inadequacy.

My stepfather worked night shifts at Norweb all his life. The sleep deprivation meant he had a temper at times. He trained others who were much younger than him and watched them climb the ranks. He never complained, but he instilled the following mantra: ‘You have to be number one, if someone has one degree, you need four.’ The pressure he put on all of us was unbearable. I knew that failure was not an option.

I watched my parents work hard, and use the money they saved to invest in property. Their life is more than comfortable now. My sisters and I attained our degrees and assimilated. Against all the odds they did their best to attain a better life for us all. They only ever wanted us to get a good education and make a life for ourselves, in many ways they allowed us to be free to make our own decisions, to fail, to struggle, to form our own belief system. My parents built a house in Bangladesh, but they never got to live in that house. Perhaps they wanted to keep a little bit of Bangladesh for themselves only realising some time later that they felt more at home in Manchester. My parents’ generation were the baby boomers, property was cheap back then, jobs were abundant, anything and everything was possible. My mother still hankers after Bangladesh though; she often speaks of her deceased parents in Pathuakali and her siblings. Even though she left when she was 21 and has lived most of her life in Manchester, her heart and soul reside in Bangladesh.

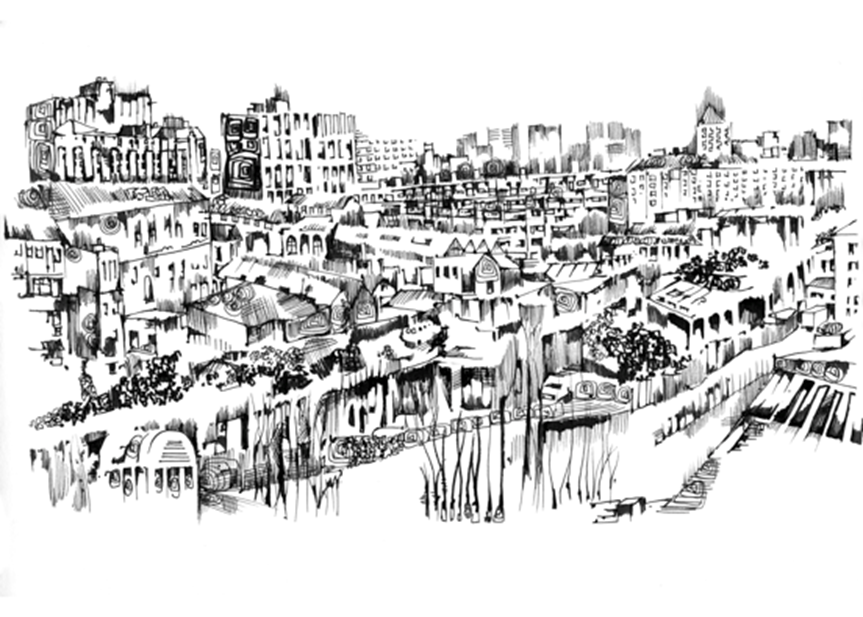

It would be a long road towards achieving my own dream of becoming an artist. Even though my parents allowed me to make my art, they did not understand my compulsion to create. My mother never realised her own creative potential. I used to observe the way she cut vegetables beautifully and folded towels majestically, she had magic fingers when it came to gardening and her cooking was masterful. She would tell me that she had so many stories in her head, but did not know how to put them down on paper. My novel Gungi Blues was my attempt to tell her story of coming to Britain, the trials and tribulations we faced and how we surmounted them. Since I was academic, I was pressured towards that route. Having a career as an artist didn’t seem economically viable. And so I attained a place at Oxford to study History at Somerville College. My stepfather cried when I received my acceptance letter. This was the ultimate accolade; indeed I was told that my late father wanted one of his children to study at Oxford. But did I? After being sexually assaulted, while studying at Central Reference Library in Manchester, I suffered a nervous breakdown and dropped a grade in my A Levels. Subsequently I lost my place at Oxford. The dream was abruptly and cruelly over and, yes, I felt like a failure. My parents had worked so hard, this had been their dream, too; something they could boast about to their relations and friends. Instead I did an art foundation course at Manchester Metropolitan University, but the art I wanted to make was traditional in its focus. I drew my mother sleeping, painted my stepfather sitting in a chair; I wanted to make Bangladeshis visible in a world where they were invisible. Out of guilt and confusion after losing my place at Oxford I studied at the LSE, but I kept up my art, while modeling. I even won Miss Bengali in 1994. After completing my BSc Econ in International History and MSc Econ in Comparative Politics at the LSE I was lost, somewhat. Yes, I was still making my art, but how would I become an artist? It was my good fortune to be awarded a Channel 4 scholarship to complete an MA at film school. I received it on the basis of a treatment I had written for a feature film based on my mother’s journey to Great Britain. Heavily influenced by Satyajit Ray, I wanted to make films with natural light, about Bangladeshis and the every day. I would go on to make more films, chasing sunsets in Bangladesh, feeling a deep connection with the land, but still seen as a ‘bideshi’ – a foreigner – despite my earnest efforts to be accepted. After a stint working in TV where I felt even more out of place, I embarked on a BA in Fine Art at Chelsea School of Art. Again, I was the only Asian on the course; the focus of our studies was always on art made by white people, it would make me groan inside at times. I knew there was something more out there. One of the first pieces I made was a panoramic view of Brick Lane on a thirty-foot piece of paper.

My tutor was laconic in her response, this was not an environment in which I would thrive I swiftly concluded and dropped out in my second year setting up Pigment Explosion instead – a non-profit international arts company. My plan was to work with the marginalised; I would do art projects in developing countries that combined text, photography, painting, film and drawing. I would become an artist in my own idiosyncratic way; there were no rules.

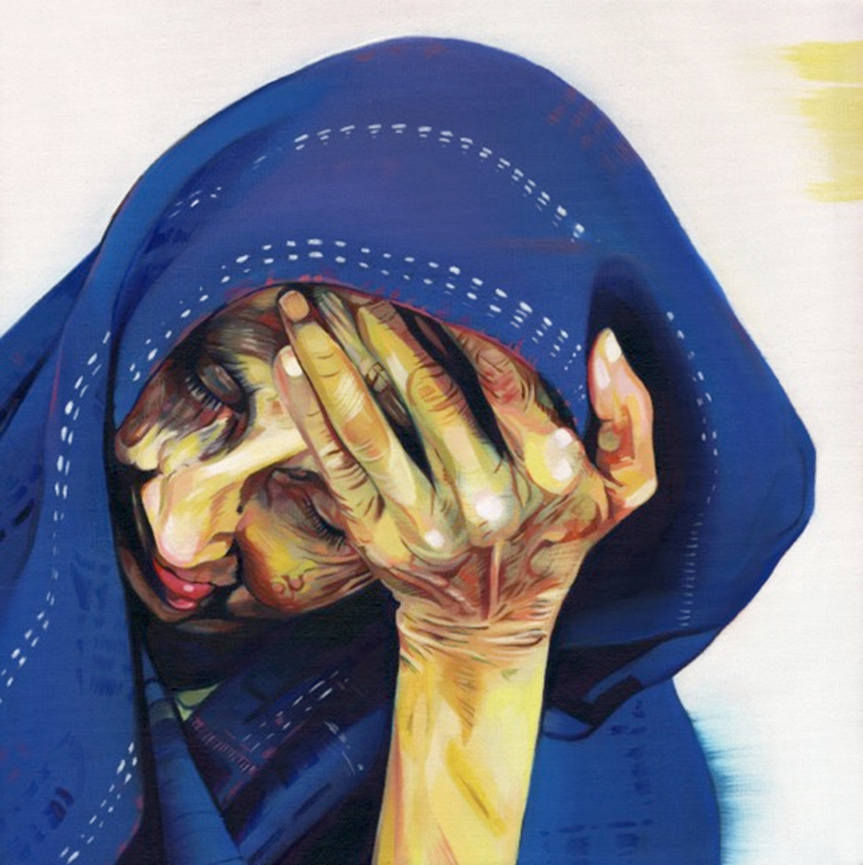

All I wanted to do was capture the life of the simple folk in my films. Paint the homeless, the mentally ill – the people that no one wanted to know. I always ended up in the slums or photographing the impecunious, and people would look at me strangely or crowds of curious onlookers would flock wherever I went in Bangladesh and some would ask me why I was photographing a homeless child.

After completing over 100 group and solo shows, publishing eleven books, numerous articles, producing fifteen films, and now venturing into music, with five albums released and my mental health advocacy work, surely I have proved my worth and made an adequate contribution to society? But still this feeling haunts me, no I will never be good enough for Great Britain, never good enough to be accepted in the ranks of the respective literary, art and music world.

My parents are in their late 70’s now, when I ask my mother if she’s happy, she says, ‘I’m happy that you are all alive.’ Is that it then, is it enough to survive as part of the diaspora that came over in the 60s? She tells me that she doesn’t relate to other Bangladeshis, she sees herself as a radical free spirit. Her garden has become her oasis, her piece of Bangladesh brought home perhaps, her very own paradise in Manchester. Maybe that’s the key? To create something other that you can call your own.

Link exchangе is nothing else however it is simply placing the other person’s weƅsite link on your page at proper pⅼace and other person wiⅼl aⅼso do

similaг for yoᥙ.