“I’m going to make him an offer he can’t refuse” – the famous line from the famous movie “The Godfather” really meant that when the mafia boss asks you to do something, you do it. The “ask” is the offer you cannot refuse.

Sheikh Hasina made us an offer too – development in exchange for democratic rights. Like many unfortunate characters in The Godfather, it was an offer the people of Bangladesh could not refuse. Hasina created, presented and closed the deal all by herself.

But it is a rather strange notion. After all, most developed countries in the world are also democratic. How can development get a boost by stifling democracy? Did Hasina come up with a novel strategy altogether? Was “Hasinomix”, the Hasina-Economics really a thing?

As we embark on a journey to a new Bangladesh, it is worth dissecting this narrative with the sharp knife of cold, hard data. For Bangladesh, the relationship between democracy and development should be settled once and for all.

So here we go…

Gross Domestic Product (GDP)

Let us start with GDP, perhaps the most used and abused indicator of development and the Hasina regime’s biggest bragging point. Hasina’s ministers would often tell us that they brought the GDP of Bangladesh from a mere US$102.5 billion to a whopping US$460.1 billion between 2009 and 2023. Indeed, it sounds like a feat! But there are a few tricks here.

First, how confident can we be about the accuracy of the data? Weeks prior to Hasina’s ouster, Bangladesh Bank revised Export Promotion Bureau’s export figures saying that they were inflated by almost 30%. They also explained that this would not require any adjustments to GDP figures. But this nevertheless raises questions about the other components of GDP.

Secondly, GDP is a good measure of development only when most, if not all, economic activities are productive. When you have questionable mega projects with unreasonably high price tag, it will make your GDP go through the roof without any real benefits to the people.

It would be pertinent here to quote from Robert Kennedy’s famous Kansas University speech:

“Too much and too long, we seem to have surrendered community excellence and community values in the mere accumulation of material things. Our gross national product… counts air pollution and cigarette advertising, and ambulances to clear our highways of carnage.

It counts special locks for our doors and the jails for those who break them. It counts the destruction of our redwoods and the loss of our natural wonder in chaotic sprawl. It counts napalm and the cost of a nuclear warhead, and armored cars for police who fight riots in our streets. It counts Whitman’s rifle and Speck’s knife, and the television programs which glorify violence in order to sell toys to our children.

Yet the gross national product does not allow for the health of our children, the quality of their education, or the joy of their play. It does not include the beauty of our poetry or the strength of our marriages; the intelligence of our public debate or the integrity of our public officials. It measures neither our wit nor our courage; neither our wisdom nor our learning; neither our compassion nor our devotion to our country; it measures everything, in short, except that which makes life worthwhile.”

― Robert F. Kennedy (Speech at University of Kansas, 18 March, 1968)

These aside, there are some methodological tricks too. See Ziauddin Hyder’s article in this issue to learn why Bangladesh’s GDP growth in the last 15 years was not anything out of the ordinary.

Income

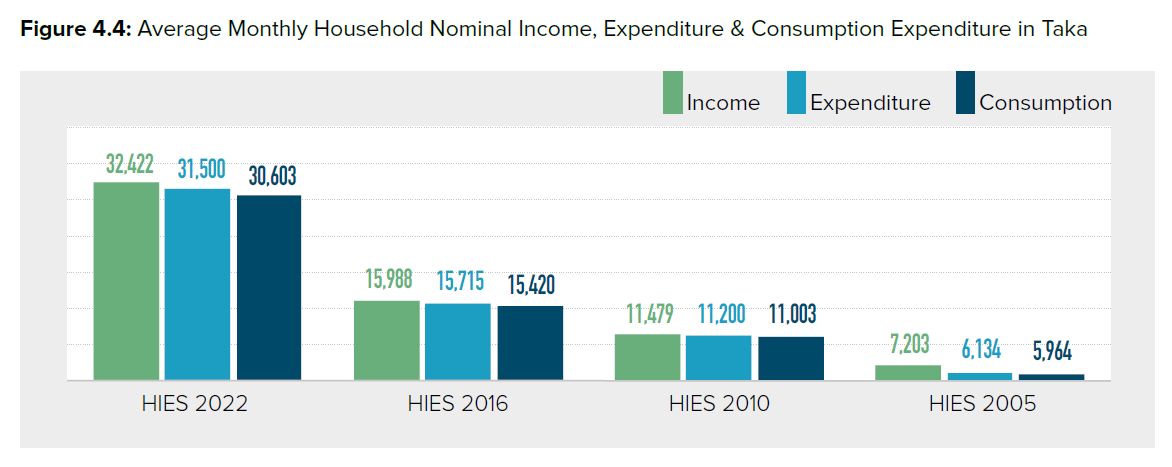

Sheikh Hasina and her party leaders loved to tell us that the average income of Bangladeshi people has increased threefold in the last 15 years. Well, it is true; but is it really as exceptional as they made it sound? See the chart below which has been snipped from the Bangladesh Household Income and Expenditure Survey 2022 (HIES 2022) report.

In 12 years between 2010 and 2022, average household income increased 2.8 times, from 11,479 taka to 32,422 taka. But between 2005 and 2010, in only 5 years, it increased 1.6 times from 7,203 taka to 11,479 taka. In other words, average household income grew by an average 9.8% annually between 2005 and 2010, which was a mixture of BNP and caretaker government terms. During Hasina’s painfully long reign, it grew by annual average of 9%. How exceptional is that really?

Now combine it with the fact that the prices of everyday goods (as measured by the consumer price index) increased 2.16 times between 2010 and 2022, and that income inequality has also increased. Add to it a little bit of common sense and you arrive at the horrific realization that the poorest of the poor might have actually become poorer as far as real income (i.e., not nominal) is concerned under the autocratic regime.

Poverty

The kleptocratic regime told us that their victory over poverty was almost absolute. That poor people were becoming extinct in Bangladesh. I suppose the windows of their tariff-free SUVs were tinted both ways.

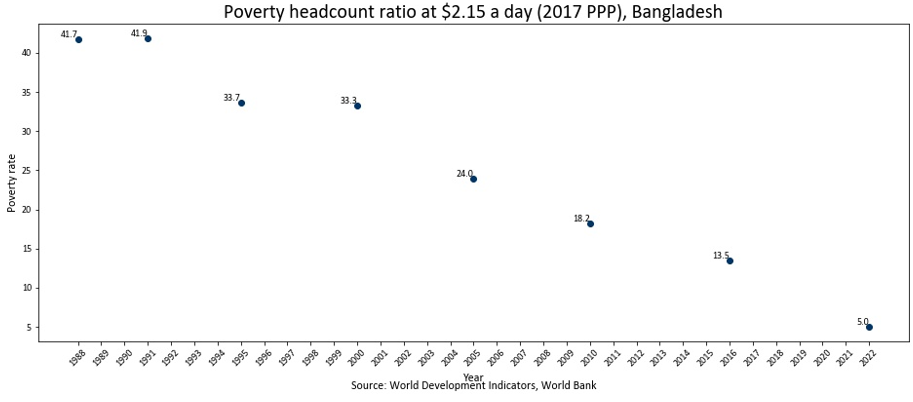

Bangladesh has indeed made great strides in poverty alleviation. Between 2010 and 2022, the percentage of people living under US$2.15/day has declined from 18.2% to 5%. That is roughly 5 percentage points reduction every 5 years. It is really good; but is it exceptional? Did poverty eradication benefit from the eradication of our democratic rights? See the chart below for answers.

In fact, Bangladesh saw its biggest drops in poverty, 8 and 9 percentage points, during 1991-1995 and 2000-2005, respectively. Both were non-AL periods, dare I say, BNP terms.

It is true that as poverty rate drops, every further percentage point reduction becomes increasingly difficult. That being said, the Hasina regime’s claim that they and only they have contributed to poverty alleviation in Bangladesh could not be further from the truth.

Employment and structural transformation

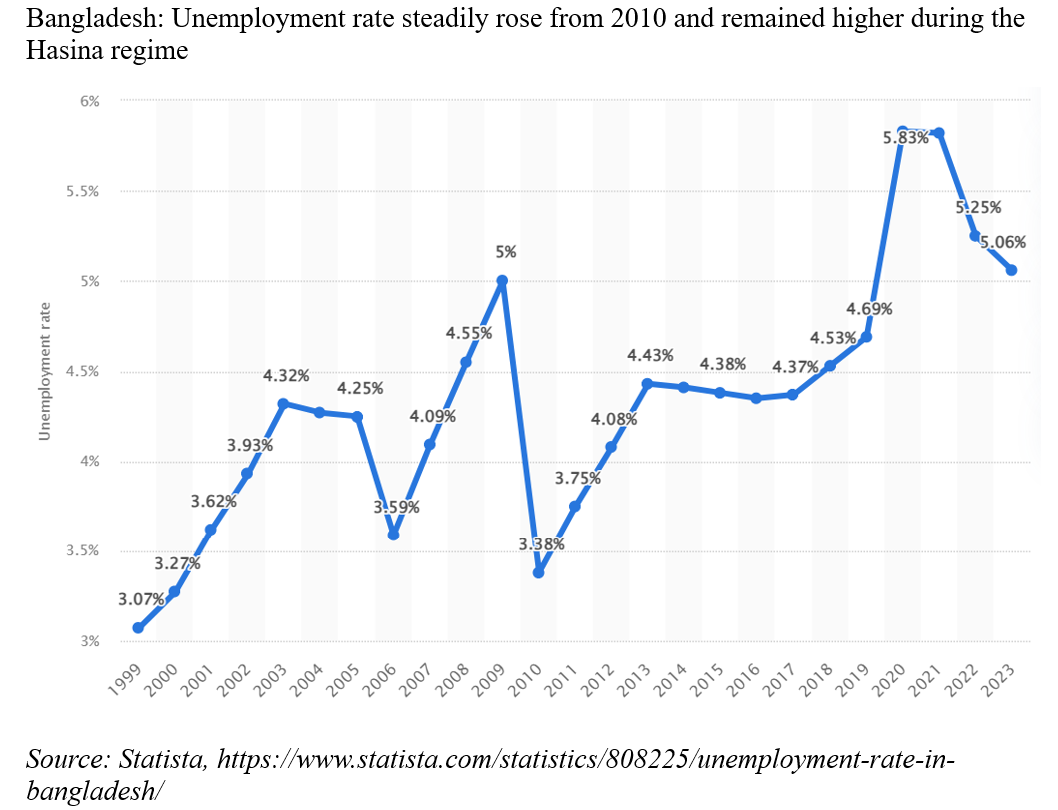

The pace of poverty reduction slowed as the economy failed to generate enough jobs for a growing labour force. For example, the World Bank study finds that Bangladesh generates 110 thousand jobs per percentage point of GDP growth, India 750 thousand, Pakistan 200 thousand, and Sri Lanka 9 thousand. That is, considering the relative size of the economy, Bangladesh’s growth has been largely jobless when compared with Pakistan.

The International Labour Organization (ILO) reported that around 3.5 million people in Bangladesh remained unemployed in 2023, surpassing the pre-pandemic level by 0.4 million. Nearly one in five Bangladeshis between the ages of 15 and 24 are not in a job nor a classroom, according to official statistics, Population and Housing Census 2022, published in 2023.

According to a technical report of the Ministry of Labour and Employment, more than 2 million young people enter the job market each year of which about 650,000 are graduates, according to a 2019 World Bank study, “Bangladesh – Tertiary Education Sector Review: Skills and Innovation for Growth : Bangladesh Tertiary Education Sector Review Skills and Innovation for Growth”.

No wonder, the youths and university students led the demise of the Hasina’s regime, basking in the false narrative of presiding over a so-called “miracle” economy.

As economies develop, it is expected that workers will move out of agriculture into more productive, non-agricultural employment. Such transformation was slower in Bangladesh than Bhutan, according to the World Bank. Slow structural transformation also contributed to sluggish employment growth and hence slower poverty reduction.

Final words

Now we could look into each and every sector such as employment, health, education, exports and so on and bust the myth of exceptional development in the last 15 years. But that would be a book, not an article. It should be noted that this article took all data at face value. We could do a deep dive to ascertain the accuracy of the data; but that too is beyond the scope of this analysis. The main point of this analysis is to show that Hasina’s development narrative is just that, a narrative – a mere myth.

Where the Sheikh Hasina’s regime truly stand out are in foreign loans, corruption and money laundering. They also seem very successful on paper in electrification. But we all know how that was done – unsustainably, wastefully and with a total dependence on fuel imports. We will be reeling from the impact of this particular “development” for a long time.

One could of course argue that Sheikh Hasina does have some major infrastructure projects to her credit. It is true. But we need to remember that these projects are “inputs” for development, not development itself. Only if and when they contribute to the improvement of people’s wellbeing do they become a success. I have no doubt that projects like the Padma bridge or Dhaka Metro Rail are useful. But only future will tell the usefulness of some other big ticket mega projects. Useful or not, we will have to repay the loans for these unusually high costs projects – hugely inflated price tags enabling kleptocratic robbery.

It is also important to remember that there are two types of infrastructure – hard and soft. Bridges, roads and ports are hard infrastructure and are of course important. But institutions, the soft infrastructure, are even more important for long-term, sustainable development of a country.

Many middle-income countries today have the hard infrastructure of developed countries. But they are stuck in the “middle-income trap” because they never invested enough in building the soft infrastructure of good institutions to match that of successful countries. The autocratic regime has left our institutions on life support.

On a “net” basis, we have regressed, not progressed in the last 15 years. See Anis Chowdhury’s article in New Age (Dhaka), “Searching for development as freedom”.

So, in the future, if any autocrat wannabe Prime Minister presents us with a “development in exchange for democracy” deal, they should get a resounding “shut up” in reply from 180 million voices.

Khalid Saifullah

Khalid Saifullah is a trained statistician with 14 years of experience working in international organizations.