The student-led anti-discrimination movement has brought an end to the long-standing Awami League government, leading to the formation of an interim government to manage the country. A national debate is now underway about the future direction and governance of the country. There is a consensus on the need to ensure that autocracy does not re-appear. Various reform proposals have been made to achieve this goal, but one reform measure that could play a particularly crucial role is the introduction of a proportional representation (PR) system, replacing the current ‘winner-takes-all’ (WTA) electoral system.

Under PR, no party will be able to establish autocratic rule by gaining a large parliamentary majority through leveraging on a slight edge in the popular vote. Instead, parties that do not receive the highest number of votes will still have a presence in parliament in proportion to its share of the vote. This will help balance the power and safeguard the country from authoritarianism. In short, while WTA exacerbates political inequality, PR can reduce it and consequently decrease inequality in other aspects of national life as well.

International scene regarding election methods

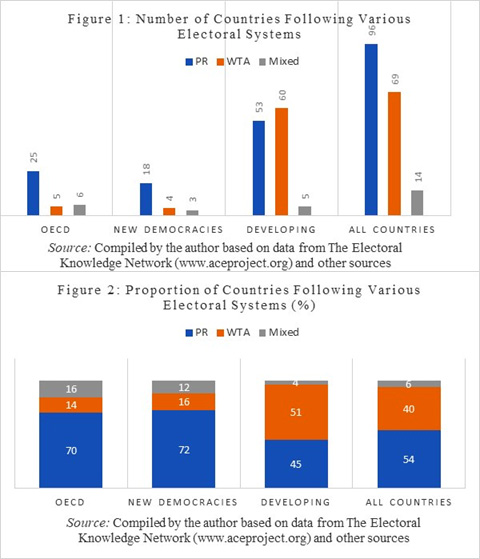

Taking a global view, electoral systems can broadly be divided into two categories: proportional representation (PR) and “winner-takes-all (WTA).” Due to the British heritage, Bangladesh follows the WTA system. However, various types of PR are more widely practiced worldwide. A recent survey shows that out of 170 countries, 91, or 54%, use PR (Figures 1 & 2). Among developed nations, this ratio is even higher. Of the 36 member-countries of the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), 25, or about 70%, follow PR.

In the 1990s, of the 25 countries in Eastern Europe and the former Soviet republics that introduced multi-party governance, 18 (or 72%) opted for proportional representation. These countries were not bound by any historical precedent. However, based on international experiences, the overwhelming majority chose PR.

Among the South Asian countries, Sri Lanka adopted proportional representation long ago, and, as a result, has acquired the political maturity that enabled the country to politically navigate through the recent economic crisis swiftly. Another neighbouring country, Nepal, partially adopted proportional representation through its new constitution enacted in 2015.

Comparing WTA and PR election systems – the basics

A significant reason why most developed countries use PR is that it is far fairer than WTA. An example can illustrate this point. Under the current WTA system, elections are held on a constituency basis. The candidate who receives the most votes in a given constituency wins.

Suppose there are five candidates from five different parties in a constituency. The first three candidates each receive 20% of the vote, the fourth receives 19%, and the fifth receives 21%. In this case, the fifth candidate wins. Now, suppose that nationwide, the popularity of these five parties mirrors this constituency. In that case, the fifth party would win in every constituency, meaning it would hold all 300 seats in the Bangladesh parliament, while the other four parties—who together received 79 percent of the vote—would have zero seats. This is why this system is called as the ‘winner-takes-all’ or WTA system.

In contrast, proportional representation is based on the national vote. Before the election, each party prepares a ranked list of its candidates and presents it to the electorate. Votes are cast based on party preference, and each party receives parliamentary seats proportional to its share of the national vote. For example, if a party receives 10% of the total votes, it would win 30 seats in Bangladesh’s parliament, and the top 30 candidates from its pre-announced list would become members of the parliament. In the example above, under PR, the first three parties would each receive 60 seats, the fourth would get 57 seats, and the fifth would get 63 seats. Clearly, proportional representation is far fairer than the WTA electoral system.

Polarizing effect of WTA vs. stabilizing effect of PR

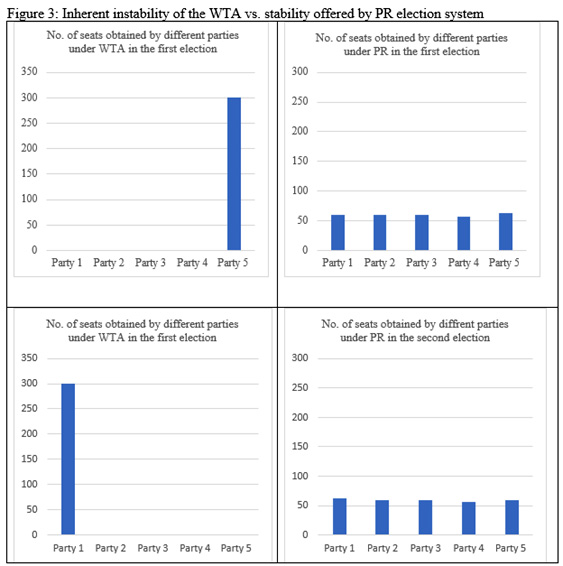

The second key advantage of proportional representation is that it stabilizes the political situation. The example above can help clarify this feature of PR as well.

Suppose the next election is held five years later, and in the meantime, the first party’s popularity has increased by 1 percentage point, rising to 21%, while the fifth party’s popularity has dropped to 20%. The popularity of the second, third, and fourth parties remain unchanged at 20, 20, and 19 per cent, respectively. Under WTA, the first party would now win all 300 seats, while the other parties, including the fifth, would hold no seats.

Thus, a mere 1 percentage point change in popularity would wipe out the fifth party’s seats, while the first party’s representation would surge from zero to 300 seats! Under proportional representation, however, the first party’s seats would increase from 60 to 63, while the fifth party’s seats would decrease from 63 to 60. The second, third, and fourth parties’ seats (60, 60, and 57) would remain unchanged, as their vote share did not change (Figure 3).

Amplifications and reversals of electoral outcomes caused by WTA in Bangladesh

Thus, while WTA is destabilizing, PR promotes stability. The destabilizing effect of WTA manifests itself in both “amplification” and “reversal” of outcomes. The example above illustrates the amplification effect, showing how a change in vote share by 1 percentage point can lead to a 300-percent (in strict mathematical terms, infinite!) change in the number of seats. Sometimes, WTA can produce a perverse outcome whereby a party can increase its vote-share only to see its seat-share decrease.

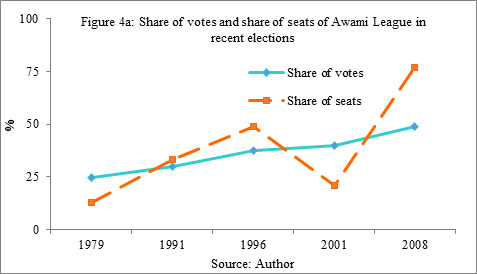

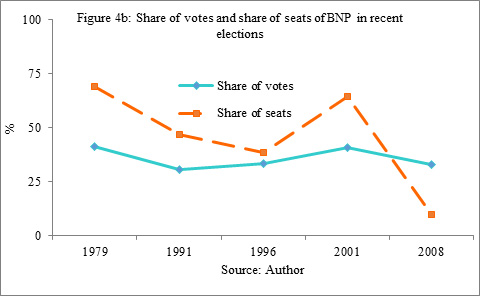

The history of Bangladesh’s elections provides illustrations of both amplifications and reversals. For example, between 2001 and 2008, the Awami League’s vote-share increased by 8.87 percentage points, yet its seat-share increased by 50 percentage points (number of seats increasing from 62 to 230). Similarly, during the same period, the BNP’s vote-share decreased by 13.83 percentage points, but its seat-share decreased by 62 percentage points (number of seats decreasing from 216 to 30).

As for reversals, for example, between 1996 and 2001, the Awami League’s vote share increased from 37.4% to 40.1%, and yet its number of seats collapsed from 146 to 62! Similarly, between 1991 and 1996, the BNP increased its vote share from 30.8% to 33.6%; yet its number of seats decreased from 140 to 116. (See Figures 4a and 4b.)

One reason why ruling parties in Bangladesh are often reluctant to hold free and fair elections is the fear of being ‘wiped out’. Proportional representation will allay that fear. Despite some fluctuations in popularity, parties will maintain their rightful presence and influence in the parliament and the political arena. This feature of PR can be particularly beneficial for Bangladesh. However, in the specific context of Bangladesh, proportional representation can offer many additional benefits. Some of these are mentioned below briefly.

Additional benefits of PR for Bangladesh

i) Reduction of the objective scope and subjective incentives for manipulation and abuse

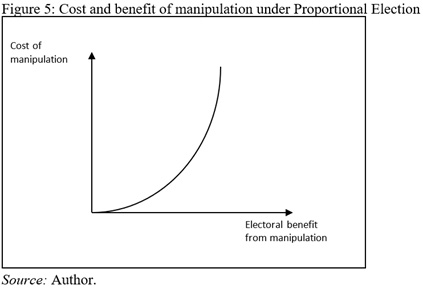

Since PR prevents large changes in outcome arising from small changes in vote shares, it implies that PR reduces the objective scope for manipulation. Only large changes in vote-shares can yield large changes in seat-shares. However, marginal cost of vote-share change is likely to increase sharply so that the total cost will be prohibitively high (Figure 5).

Also, under WTA, the future of local candidates is determined by outcome of local voting, and hence there is a tremendous pressure on local candidates (who invest a lot of their personal money in their campaign) to win the seat by hook or crook. PR however severs the connection between local political leaders’ fortunes and the election outcome and thus reduces the subjective compulsion for them to engage in manipulation.

Also, under WTA, the future of local candidates is determined by outcome of local voting, and hence there is a tremendous pressure on local candidates (who invest a lot of their personal money in their campaign) to win the seat by hook or crook. PR however severs the connection between local political leaders’ fortunes and the election outcome and thus reduces the subjective compulsion for them to engage in manipulation.

ii) Promotes better quality candidates

Since voting under PR will take place at the national level, all parties will be compelled to include in their party-lists people who have earned national recognition through their contribution to the discussion and formulation of national policies. Thus, people of much better calibre will get into the parliament. By contrast, under WTA, people who can exert influence at the local level, often through money and muscle power, get elected to the parliament. Also, through a feedback process, PR will encourage people of better quality to join political parties and be active in them. This is because it will allow them to be included in the party-lists and thus get into the parliament and play a role in national policy formulation.

iii) Improves the quality of election campaign

Being based on local constituencies, WTA leads the election campaign to be focused on local, parochial issues. By contrast, PR, being an election at the national level, leads the election campaign to be focused on national issues. The campaign can thereby be uplifting rather than debasing.

iv) Eliminates the necessity of pre-election alliances

Under WTA, parties often form pre-election alliances, hoping to increase their vote-shares even by a small extent which can lead to large changes in seat-shares. This often leads to ‘unholy’ alliances, based on guesses regarding popularity of parties, and confuse the public about true character of various parties. Under PR, there is no need for pre-election alliances, so that parities can reveal their true selves. Any alliance (to form government) can be post-election and based on actual popularity (proven through the election results) of various parties.

v) Strengthens political parties

Under WTA, political parties face centrifugal forces that pull them in as many directions as are there constituencies and thereby weaken them. People can get nomination just on the basis of their money and muscle which they can present as their qualification. If they do not get nomination, they can become ‘rebel’ candidates. Under PR, by contrast, parities compete as a whole, and not in individual constituencies. This generates a centripetal force and strengthen parties. Also, since party-lists have to be adopted through national conferences, people aspiring to be on the list have to work for the party throughout the inter-election period in order to gain recognition and popularity within the party. Also, under PR, there is no scope for being a rebel candidate. PR also obviates the necessity of the same individual to be candidate from multiple constituencies.

vi) Creates better conditions for functioning of local governments

Under WTA, a conflict arises between the members of the parliament (MPs), on the one hand, and local government officials, on the other. The former exerts themselves in the local government affairs, thus harming the functioning and development of local governments. Under PR, MPs will be not connected with local constituencies and their role will be limited to policy formulation at the national level. This can ensure better conditions for local governments to flourish and perform their responsibilities.

vii) Creates level playing field and is more inclusive

Under WTA, small parties face a discrimination. While they may have a sizable vote across the country, often it is not concentrated in particular constituencies in order to gain majority there. So, they face Catch 22. They do not get vote because they are not expected to get the majority in particular seats, and they cannot become a majority because they cannot get vote. PR can end this discrimination, because it does not require a party’s vote to be concentrated in particular constituencies. Thus, it creates a level playing field and allows small parties to gain seats in the parliament, in proportion to their popularity at the national level, making it more inclusive.

viii) More just and conducive to peace

The above shows that, in contrast to WTA, PR is a fairer system. It ensures that each party’s seat share is equal to its vote-share; it creates equal opportunity for all parties to get into the parliament; and it creates equal opportunity for all members of a party to be included in its party-list. There is a saying that “There is no peace without justice!” By being just, PR can also conduce to peace.

Potential problems of Proportional Representation in Bangladesh

Despite the merits above, PR has some potential drawbacks. It is necessary to discuss ways of mitigating them.

i) Lack of geographical representation

One of the problematic features of PR, as noted earlier, concerns geographical representation. Since the election is constituency-based, equal representation in the parliament of all parts of the country is not assured. However,

a. first, for a geographically small and compact country as Bangladesh is, the issue of uniform geographical representation may not be that serious.

b. Second, to garner votes from all parts of the country, all parties will likely be interested in including in their lists candidates from all parts of the country.

c. Third, if it is absolutely necessary, PR can be applied at the level of the old divisions – Dhaka, Chittagong, Rajshahi, and Khulna – instead of the national level. However, this will lower the effectiveness of PR.

d. Fourth, the role of the parliament is to formulate national interest and not to represent interest of different parts of the country. In that sense, independence from geography can actually be helpful for formulation of better national policies.

e. Fifth, the strengthening of the local government will allow local demands to be better voiced and fulfilled.

f. Finally, a National Forum of Upazilla Chairpersons may be created, and the budget may be discussed at this forum before it is approved by the Parliament.

ii) Frequent changes in the government

Another contention that is often made against PR is that it may lead to more fractious parliament, increase the necessity of alliances, and result in unstable governments and political instability. However,

a. first, frequent changes in government does not necessarily mean political instability, if those changes happen through proper parliamentary rules, as is the case of Italy and some other developed countries.

b. Second, international experience shows that whether or not coalition governments are needed depend more on underlying political landscape than on PR. For example, India has the same WTA since its independence and it had stable governments formed by the Indian National Congress for decades. Yet, with the rise of the political power and parties of the Dalits, the political landscape changed, and India started to have coalition governments and frequent changes in the government. In Bangladesh too, coalition governments were formed despite WTA, when the correlation of political forces demanded them.

c. Third, as compared to those formed under WTA, coalition governments under PR are better because these are formed on the basis of measured or actual (instead of guessed) vote-strength of individual parties and also because the parliament will be more inclusive so that the governments are likely to be more representative.

iii) “Piggy-backing” and “Nomination trade”

A third contention against PR is that it may encourage people to “buy” their way into party lists and “piggy back” on the popularity of the party and become members of the parliament without having to face the test of their personal popularity among the electorate. However, a number of caveats can be made:

a. In Bangladesh, nomination trade is rampant under WTA, in which the nominees are selected by nomination boards of political parties, without any participation of the rank-and-file of the parties. The fact that the candidates bear personal responsibility for winning in their constituencies and the nomination Board can always shift the blame for defeat on the candidates, make it easier for the Board to engage in nepotism, favouritism, and other malpractices (such as offering nomination in exchange for large donations to the coffers of the parties).

b. Under PR, however, the party-list has to be formed at a national conference with participation of the entire party, because otherwise the list will not be perceived as the list of the party as a whole and it will be difficult to mobilize entire party in its support. Also, the party leadership will have to take the direct responsibility for the outcome of the election because the outcome will be decided at the national level and not at constituency level on the basis of the performance of an individual candidate.

Hence, contrary to the aforementioned perception, the scope for piggy-backing and nomination-trade will in fact be less under PR than under WTA. Finally, more sophisticated variants of PE can allow even the voters have a say in the choice of individual candidates from the party lists, thus reducing the scope for piggybacking further. Once a PR system is adopted, Bangladesh too can move forward to its more sophisticated variants.

Possibility of adoption of PR in Bangladesh

The support for PR was already increasing in Bangladesh before the 2024 July mass uprising led by students. Most of the Left parties were all along for PR. General Ershad and his Jatiyo Party became a proponent of PR even before the election of the 11th Parliament and this party continues to hold this position. Before the election of the 12th Parliament, the Bangladesh Islami Andolon opted for PR.

Many prominent intellectuals, including Prof. Sirajul Islam Chowdhury voiced their support for PR. Many of the more thoughtful Awami League leaders voiced their support at informal gatherings for PR. The same has been the case with BNP, whose leader Nazim Kamran Choudhry wrote considerably, advocating PR. The Election Commission that held the election in 2008, included adoption of a partial PR system in its recommendations for the future.

The organization “Rashtrya Songskar Andolon” made introduction of PR as one of its main demands regarding reform of the political system. Hence, it will not be an overstatement to say that political support for PR was steadily increasing. The experience of consecutive questionable elections in 2014, 2018, and 2024 made people psychologically ready to consider radically different options that could end vexed issue of proper elections.

The mass uprising of July-August, 2024 has now created much more favourable conditions for the introduction of PR in Bangladesh. Many more political parties, including the influential Jamaate Islami and Nagorik Odhikar Parishad, have called for PR. More intellectuals have come forward in support of PR. The outgoing Election Commission, in its parting messages have called for PR. In fact, Kazi Habibul Auwal, the Chairman, have written a persuasive piece, providing arguments for PR and characterized Bangladesh as the ideal place for the application of PR.

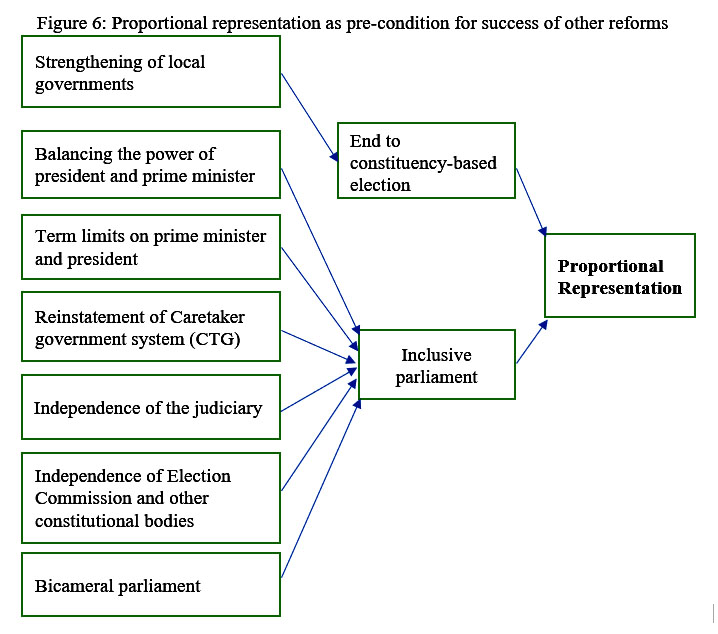

The success of most of the reform proposals that have been put forward from different corners of the society depends on a sufficient degree of inclusiveness of the parliament that only PR can ensure. These include proposals to:

i. balance the power of the prime minister and the president;

ii. putting term limits on the president and the prime minister;

iii. reinstate the system of caretaker government for holding elections;

iv. ensure the independence of the judiciary;

v. ensuring the independence of the Election Commission and other constitutional bodies; and

vi. introduction of bicameral parliament.

In addition, PR is also the precondition for the success of reforms for strengthening of local government institutions as illustrated in Figure 6. This is because, as we saw above, this cannot happen unless the current stranglehold on the local affairs by the MPs elected from individual constituencies is removed through introduction of PR.

Concluding remarks

The WTA election system has been a legacy of the British colonial rule. It has been very damaging for flourishing of democracy in Bangladesh. It has the inherent tendency to polarize political forces. In Bangladesh, this polarization has attained a particularly deadly and bloody form. It was a great failure for political parties to not introduce PR in 1991 when a transition was made from the quasi-military rule to democracy. The rise of the autocracy that Bangladesh, witnessed later, was to a great extent a result of this failure and the continuation of the WTA system. The 2024 July mass upsurge has now created another opportunity for Bangladesh to end the WTA system and introduce the PR system which will force the opposing political parties to coexist and cooperate, knowing that no one can extinguish the other. Perhaps, this forced accommodation will ultimately lead Bangladesh to a more tolerant political culture and stable democracy. It is the duty of all to ensure that this historic opportunity is not missed.

Nazrul Islam

Nazrul Islam is the former Chief of Development Research, United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. He is also a former teacher of Dhaka University economics department. Currently, he is a Visiting Professor of Asian Growth Research Institute of Japan and a part-time teacher of Columbia University in the USA. E-mail: nislam13@yahoo.com.

The author has written extensively on this issue. For example,

Islam, Nazrul (2001a), “The institutional approach to political stability in Bangladesh,” The Journal of Social Studies, No. 93 (July-September), pp. 80-100.

Islam, Nazrul (2008), “Can proportional representation help stabilize democracy in Bangladesh?” Journal of Bangladesh Studies, No. 10, pp. 52-60

ইসলাম, নজরুল (২০১১খ), “বাংলাদেশের রাজনৈতিক স্থিতিশীলতার লক্ষ্যে দুটি প্রস্তাব,” প্রতিচিন্তা, প্রথম সংখ্যা।

Islam, Nazrul (2016), Governance for Development: Political and Administrative Reforms for Bangladesh, New York: Palgrave-Macmillan.

ইসলাম, নজরুল (২০২৪ক), “আগামী বাংলাদেশের দশ করণীয়,” বিআইডিএস পাবলিক লেকচারঃ নিউ সিরিজ নং ১২, বাংলাদেশ উন্নয়ন গবেষণা প্রতিষ্ঠান, ঢাকা

ইসলাম, নজরুল (২০২৪খ), “আগামী বাংলাদেশের দশ করণীয়,” সমাজ অর্থনীতি ও রাষ্ট্র, সংখ্যা ১৩, এপ্রিল, পৃ ১১৭-৪৪৬।

ইসলাম, নজরুল (২০২৫), উন্নয়নের জন্য সুশাসন, ইউনিভার্সিটি প্রেস লিমিটেড, ঢাকা (প্রকাশের পথে)