Introduction

I worked as an international consultant for some 30 plus years (1991-2024) in many countries in Asia and Africa. In Bangladesh alone, I did 25 different projects over this period dealing with various types of infrastructure development such as roads/bridges vis-à-vis social and resettlement risk assessment, resettlement planning and management. To my knowledge, there are not many international consultants who have worked in their native countries to the extent I did in a variety of project settings and contexts. In this short essay, I share my experiences and encounters as a ‘foreign’ consultant in my ‘native’ country and how I navigated my dual identity as an ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ at the same time.

Since all writings is a social process involving interactions with individuals and groups, the narratives in this essay are derived from my engagements as a social/resettlement specialist at the project-level and interactions I have had with various departments/agencies and project staff. The stories reported here are, therefore, both personal and professional, intertwined with and grounded in academic and applied work. These stories have pedagogical value and provide insights into practices and learnings in the development processes.

My projects and policy work

As a consultant, I was involved in a wide range of projects funded by international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the World Bank (WB). Some of the key projects in my portfolio include the Jamuna Multipurpose Bridge Project, the Road Rehabilitation and Maintenance II Project, the Gas Infrastructure Development Project, the Dhaka Urban Development Project, the Bhairab Bridge Project, the Southwest Road Network Development Project, the Chittagong Port Project, the Jamuna-Meghna River Erosion and Mitigation Project, the Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project, Regional Cooperation and Integration (RCIP)-Rail and RCIP-Roads Projects, Dhaka Flyover Project and Metro Rail Project.

As a consultant, I was involved in a wide range of projects funded by international financial institutions (IFIs) such as the Asian Development Bank (ADB), Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and the World Bank (WB). Some of the key projects in my portfolio include the Jamuna Multipurpose Bridge Project, the Road Rehabilitation and Maintenance II Project, the Gas Infrastructure Development Project, the Dhaka Urban Development Project, the Bhairab Bridge Project, the Southwest Road Network Development Project, the Chittagong Port Project, the Jamuna-Meghna River Erosion and Mitigation Project, the Padma Multipurpose Bridge Project, Regional Cooperation and Integration (RCIP)-Rail and RCIP-Roads Projects, Dhaka Flyover Project and Metro Rail Project.

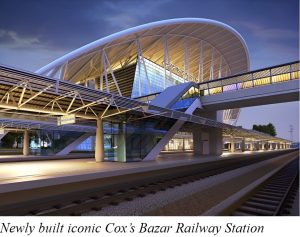

The RCIP-Rail Project involved review and preparation of seven subprojects to modernize the Bangladesh Rail network system, including double-tracking existing rail lines, establishing new networks such as the Chittagong-Cox’s Bazar Rail project, and finally, adding connectivity with India and Myanmar and the Trans Asian railway. Under the RCIP-Roads Project, a total of 1,000 km of road is being widened from the existing two lanes to four lanes in order to meet the growing traffic demand.

The RCIP-Rail Project involved review and preparation of seven subprojects to modernize the Bangladesh Rail network system, including double-tracking existing rail lines, establishing new networks such as the Chittagong-Cox’s Bazar Rail project, and finally, adding connectivity with India and Myanmar and the Trans Asian railway. Under the RCIP-Roads Project, a total of 1,000 km of road is being widened from the existing two lanes to four lanes in order to meet the growing traffic demand.

During the Covid period, I provided advisory services via zoom on the project preparatory work of the Jamuna River Sustainable Management Project-1 undertaken by the World Bank. As a social/resettlement expert, my task was to examine and/or minimize project impacts with regard to land acquisition and displacement and to prepare resettlement, livelihood and community re-building and reconstruction plan for those displaced by project interventions.

Encounters as a foreign/native specialist

I was a ‘foreign’ consultant in my ‘native’ country. In anthropology, the paradigm polarizing ‘western’ (i.e., those studying ‘other’ cultures as ‘outsiders’) and ‘native’ (i.e., those who write about their own cultures as ‘insiders’) anthropologists emerged in the post-colonial era and continued for some time as a dichotomy between ‘outsiders’ and ‘insiders’ in anthropological writings and discourses. I was trained in the tradition of ‘native’ anthropology, and studied my own culture and people as an ‘insider’ during my graduate studies at the University of Manitoba in the 1980s.

How ‘foreign’ is an international consultant in his own country? Perhaps, not much, particularly when it comes to engagements with project-affected communities. Naturally, my status as a ‘native’ specialist proved an advantage due to my language and understanding of the socio-cultural milieu. I was at ease working with the affected people and communities as ‘one of them’, speaking in my native Bangla language. This was extremely beneficial during surveys, interviews and stakeholder consultation meetings, as well as socializing with the affected villagers. I occasionally made appropriate cultural jokes and used fictive kin terms such as chacha (uncle) or chachi (auntie) while talking to the villagers in community settings. This earned me quite a bit of respect and allowed further probing of relevant issues. Thus, I was able to take control of the environment and at the same time appreciate local inputs provided by the participants.

Despite my efforts, I found this dichotomy very much ingrained among members of the project consulting team as ‘foreign’ consultants and local consultants where foreign consultants were technical leads in project preparatory work with assistance from local counterparts. In the office and at the project level, the local staff and officials treated me as a ‘foreigner’ or international consultant due to my status and position.

For example, the Secretary of the Jamuna Multipurpose Bridge Authority respected my work, but always treated me as a foreigner. Some of the officers even used to call me ‘Canadian Zaman’ to distinguish me from the ‘Dutch Zaman’ as there were two Zamans on the Halcrow Management Consultancy Team for the Jamuna Bridge Project. My international colleagues liked my dual identity and found me very ‘resourceful’ as a team member in project works, and often as a ‘go between’ to negotiate with senior government officials or project proponents and/or project executing agencies.

Stories from the Field

I had many amusing encounters as a ‘foreign’ and ‘native’ consultant. In 2001-2002, I worked on the Jamuna-Meghna River Erosion Mitigation Project (JMREMP), designed to establish cost-effective and sustainable mitigation measures for riverbank erosion in two flood protection and irrigation schemes – (a) the Pabna Irrigation and Rural Development Project (PIRDP), and (b) the Meghna-Dhonagoda Irrigation Project (MDIP).

The two schemes are located in different floodplain reaches of the country. The PIRDP is situated on the western bank of the lower Brahmaputra-Jamuna River, and the MDIP is located on the eastern bank of the confluence of the Padma and Upper Meghna Rivers. The primary objectives of these flood control and irrigation projects were to provide immediate protection to at least two million people from progressive riverbank erosion, to provide security against loss of crops, livestock and fisheries, and to ensure sustained economic growth, poverty reduction and livelihood security in areas threatened by flooding and erosions by the rivers.

Just before my first visit as an ADB consultant to the PIRDP site, I met the Project Director (PD) Sharif Rafiqul Islam in his Dhaka Office. He called the on-site Superintending Engineer and informed him of the visit by the ‘Canadian’ consultant to the site. The PD also informed me that a meeting of the Water Users Association (WUA) was scheduled for that day, and that I could have further consultation with the WUA members as beneficiaries of the project.

The following day, together with Nazibor Rahman, the Team Leader of the Rural Development Movement (RDM), the NGO implementing the Land Acquisition and Resettlement Plan (LARP) for JMREMP, I left Dhaka very early in the morning by road, but it took longer than expected due to winter fog on the highway. When we arrived, the meeting was already in progress, and there was a bit of interruption caused by our arrival. I sat down on an empty chair beside the speaker, who introduced himself as the Superintending Engineer, and then continued on with his lecture.

After he was done speaking, he sat down and whispered into my ear, “Where is the Canadian consultant?” I looked at him and said, “I am the Canadian consultant.” He paused, and then said, “Oh! I am sorry, I thought you were a Bangladeshi”. I smiled and said, “Yes, I am a Bangladeshi and Canadian too”. We then continued with the meeting and later had a long chat over lunch about life in Canada and my Canadian journey.

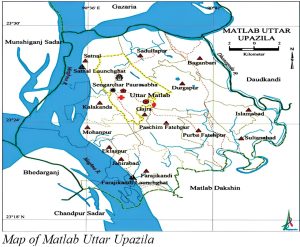

My trip to the MDIP site was even more fascinating. I literally returned to my own village as a consultant. Anthropologists traditionally return to their study villages for restudies. Consultants may have often worked in their own countries as international specialists. However, I am not aware of any one returning to his/her own village as an international consultant. The MDIP, located in Matlab Upazila (subdistrict) in Chandpur District, was constructed in the mid-1980s after I left Bangladesh for Canada.

Matlab was a one-crop low-lying area and prone to annual high flooding. Under the MDIP, the area was ‘cordoned-off’ like a polder with a 64 km long embankment. The MDIP also established a 282 km canal system and 125 km of drainage for irrigation purposes.

Matlab was a one-crop low-lying area and prone to annual high flooding. Under the MDIP, the area was ‘cordoned-off’ like a polder with a 64 km long embankment. The MDIP also established a 282 km canal system and 125 km of drainage for irrigation purposes.

People living within the MDIP now produce three rice crops annually and winter vegetables as well. The MDIP is now viewed as a ‘flagship’ project of the BWDB. The project changed the face of poverty in the region.

When the ADB Team arrived in Kalipur Bazar in the early afternoon, we were taken to the Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) guest house, which stood beside a huge pump house. The geography of the area had entirely changed due to the construction of the embankment. Still, I could see our village home from the guest house and became very nostalgic.

I was born and grew up in Kalipur, next to the local market called Kalipur Bazar. The bazar is right on the Meghna riverbank, and was originally established as a tehsil (revenue record and collection center) during the British period by my grandfather. The guest house, the pump station and other MDIP facilities are on our ancestral lands. It was a very emotional moment as I returned to my village home after some 20 years.

The international team members and local officials knew I was from the village and offered me a choice to stay in the guest house or with my family in the village. I decided to stay with my team, as it was an official visit.

After some refreshments, we got down to business with BWDB officials. We got a briefing and a programme schedule for the next three days of work, including a trip to the DC Office in Chandpur to discuss land acquisition for the new 6 km bankline protection works in the Ekhlaspur area. During the meeting, we realized that a group of people had surrounded the guest house. Our international colleagues, mostly Japanese, were a bit concerned with the crowd as being ‘protesters.’

However, we all felt relieved when a local official mentioned that some of my relatives from the village had come to see me. I took a break from the meeting and went out to meet my visitors, who included not only my family members, but also some friends of mine from high school. I studied up to Grade 8 in the village before leaving for the city, and during my college and university days, I regularly visited my village home to see my parents before they passed away in 1979 and 1980. I had not seen these people in many years. When I went out that day to greet my visitors, they were happy to see me. We agreed to meet at a teashop later that evening.

In the evening, I took a walk around the bazar (market area) with my nephews. It had grown to 10 times the size I remembered from the late 1970s, and the shops in the bazar glittered with electric lights. I made a phone call to Vancouver from a mobile shop in the bazar. It was a very euphoric moment – I almost could not believe that it was real. The owner of the shop was very young and intelligent, and I asked my nephews who he was. The answer came as another big surprise, as they told me his father was a very poor fisherman in the village, whom I knew.

Finally, we came to the teashop where I had arranged to meet with friends and local villagers. The teashop slowly filled up, and still more people stood around the shop outside. I asked the owner to serve tea to everyone. I was not able to recognize many of the people in the teashop, so I requested that everyone introduce themselves so that I could reconnect with them immediately.

Many of my fellow students from high school looked very old, as if they had aged beyond their years. One elderly person asked me whether I could recognize him, and I asked him to help me out by offering some clues. This made everyone laugh. The man reminded me that when I was young, he made all my shirts, as he was the only tailor in the market. I looked at him for a moment, then stood up and hugged him tightly. This was met with huge applause from everyone around us. Another old man came up to me and shook my hand, telling me, “I was the boatman for your family when you were very young”. Some people inquired about my family in Canada; others inquired about my salary as a consultant. It was surely an evening with memories and love that I cherish to this day!

The following day, we visited the 6 km section of the embankment in Ekhlaspur area that required new protection works. We were able to drive on the embankment, since the embankment top was paved, and thus it works as a road for easier and faster travel by people in and around the MDIP. There are many scattered settlements on both sides of the embankment, mostly occupied by poor and landless people who do not have any alternative option.

We met the people on the embankment along the 6 km stretch, conducted meetings to list their concerns. Also, we visited along with the MDIP Executive Engineer Mozammel Haque, the bankline that required protection works to save the MDIP embankments. In some places along the bankline, there were footprints of hearths and homes that people have recently abandoned due to the fast approaching erosion in the area. This was a critical stretch requiring protective works for erosion and flood control purposes.

Ekhlaspur was in the limelight due to the visit by the French President Francois Mitterrand in February 1990. President Mitterrand’s visit to Bangladesh, following the disastrous 1988 flood, was in part prompted by the French approach and desire for a mega plan, calling for the construction of massive embankments on major rivers throughout the country. We visited the area and the platform constructed for landing President Mitterrand’s helicopter. Many villagers we talked to still remember the visit by President Mitterrand. We left Ekhlaspur that evening for Chandpur to meet the DC regarding land acquisition issues for the MDIP additional bank protection work.

For me, it was just not consulting work; the trip to my village home was a renewal of relationship with the people and the locality.

Padma Bridge Planning Stories

During my work with the Padma Bridge feasibility study team (2003-2005) funded by JICA, we were tasked to select the bridge crossing location out of four alternative crossing sites – Paturia-Goalundo, Dohar-Charbhadrasan, Mawa-Janjira and Chandpur-Bhedarganj. After a year’s worth of technical and social investigations, the Mawa-Janjira crossing was selected for further investigation and bridge design.

As the Lead Land Acquisition and Resettlement Specialist, I conducted extensive consultation meetings with the affected villagers and communities at the Mawa and Janjira sites. I even drew sketches of the proposed bridge, toll stations and access roads on the ground with sticks in courtyards during consultations to explain the scale of land acquisitions, potential impacts of the bridge project, and the compensation and resettlement packages, following the example of the Jamuna Bridge Project. I also explained the Jamuna ‘packages’ in greater details, but clearly sensed that people lacked confidence in what I was telling them regarding compensation and resettlement benefits.

I still vividly recall an older person, during a meeting at the Janjira site, asking me in a distinct voice: “How can we trust the government?” He continued, pointing his finger to the highway beside the local government office where the meeting was held: “I lost my land to this highway 20 years back and still have not receive any compensation. You are promising too many good things… How can we trust you?” I explained that it would be different this time, as the construction of the bridge project would be funded by JICA, ADB and the World Bank like in the case of the Jamuna Bridge Project.

In Bangladesh, land acquisition by the government is always viewed with apprehension by landowners, because it affects household economy and incomes. Additionally, land acquisition is typically associated with unnecessary harassment of the landowners by the local revenue officials, as well as bribery, delays in payments of compensation, and social hardship. Too often, people are not paid at all in revenue or locally funded projects as in the case of the highway project above.

To overcome this lack of trust and to show what was done in the case of the Jamuna Bridge Project, I took a group of 40 community/village-level leaders, elected officials and representatives of affected persons to the Jamuna bridge resettlement sites on an exposure trip to see for themselves the Jamuna resettlement sites and the community infrastructures built by that project. During the visit, they were allowed to move around freely at the resettlement sites, talk to the resettled villagers, and visit the civic infrastructures (e.g., schools, mosques, clinics) at the sites.

For many, this was also their first opportunity to see the iconic Jamuna Bridge. As the saying goes, “seeing is believing.” This exposure trip was a very powerful way to convince the potential project-affected persons of what they could expect in the case of the Padma Bridge Project resettlement. The visitors to the Jamuna resettlement sites were thus convinced that I had been speaking the truth about the “good practices” with regard to compensation and resettlement. Many expressed their satisfaction about the resettlement sites, particularly the civic amenities at the sites. After the trip, very little effort was required on my part at the consultation meetings in Mawa and Janjira; those who visited the Jamuna resettlement sites explained it all.

When I returned to Mawa-Janjira during the Padma Detailed Design Stage (2008-2010), I was already a familiar face to the villagers. Indeed, I was perhaps the only ‘face’ of the Padma Bridge Project to the local stakeholders, who provided their strongest possible support to the Social Team and to me for our village-level survey and other works. I conducted extensive consultation meetings among the affected villagers in Mawa and Janjira and explained the valuation of assets, rates, compensation payments, resettlement options and packages, and post-resettlement income and livelihood restoration/social development programs.

In Padma bridge project, four resettlement sites were built with provisions for house plots for over 2,400 households, and including civic amenities such as internal roads, water supply, electricity, schools, a market area, and waste management systems. The resettlers in the four sites now live in secure, semi-urban townships with access to employment and other social development support.

In Padma bridge project, four resettlement sites were built with provisions for house plots for over 2,400 households, and including civic amenities such as internal roads, water supply, electricity, schools, a market area, and waste management systems. The resettlers in the four sites now live in secure, semi-urban townships with access to employment and other social development support.

People believed in what I said, and expressed their full confidence in my work related to compensation and resettlement packages. My cell phone number was given out to literally everyone in the project area. I was very much accessible both at the project office and in the field. People having difficulties related to compensation or any other project-related issues, particularly with local administration, would contact me for help, and I made sure their issues were addressed and resolved quickly.

One day, the head teacher of the local primary school in Kawrakandi called me from the DC Office in Madaripur and told me that his compensation cheques were ready, but the office clerks were demanding some cash. The school teacher asked for help to overcome this ordeal. I immediately called Shishir Kumar Sinha, DC Madaripur, whom I met many times at the project sites and his office as well. The DC assured me that the cheques will be paid “right away”. I later got a call from the school teacher, who thanked me for the help. During my subsequent trips to the project sites, I found out that the school teacher made a big story out of this and retold this many times to the local villagers.

To local villagers, any statement or assurances from the Project Director or other officials of BBA was not enough; they always wanted to hear from me before they felt convinced and assured. Due to my level of engagements with the local communities and my popularity in the project area, the project staff as well as ADB and WB officials very often teased me. Masood Ahmad, the Task Team Leader of the World Bank once said: “Zaman, you should run for the Parliament from the project area. I am sure people will vote and elect you”.

It was an incredible experience and honour working on the Padma Bridge Project. My identity as a ‘native’ as well as a ‘foreign’ consultant was very rewarding and beneficial for the team and the project. The Project Director Rafiqul Islam recognized this and had asked his staff members to follow the “steps.” I strongly believe that my ‘insider’ perspective and identity made a difference. The work equally impacted me as a specialist, and I felt extremely honoured to have gained the trust of the people at risk.

Mohammad Zaman

Dr. Mohammad Zaman is an internationally known development/ resettlement specialist. He has worked in many major projects for the World Bank in Bangladesh and in other countries in Asia and Africa. Dr. Zaman’s most recent edited book (co-editor Mustafa Alam) is titled Living on the Edge: Char Dwellers in Bangladesh, Springer, 2021. E-mail: mqzaman.bc@gmail.com