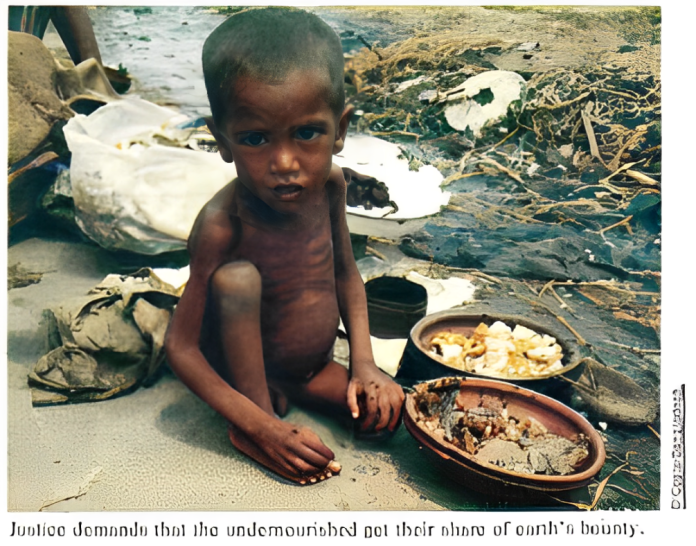

Courtesy: Jerome D’Costa’s Photo Feature: The 1974 Famine of Bangladesh, https://issuu.com/jeromedcosta/docs/famineof1974

December is a month of rituals, perhaps with some added significance compared with other such months as February or March. As usual, in this month of Victory, we are remembering our fallen – some 30 lakh Bangladeshis who have laid down their lives for the freedom of the nation.

We have special remembrance of our intellectuals who were brutally murdered on the dark night before the occupation army surrendered to the liberating freedom fighters. We are also paying homage to all those who were violated by the occupation force and its local collaborators.

But how about those who perished unjustly after the country’s liberation? Should we not have a special day for those who perished violently and in silence?

Perished violently

Tens of thousands perished at the hands of the brutal para-military forces, “Rakkhi Bahini” just because they wanted a Bangladesh free from exploitation and corruption. In his Bangladesh: A Legacy of Blood, Anthony Mascarenhas compared Rakkhi Bahini with Hitler’s Nazi Brown Shirts (a private army) having little differences between them, and the goons of the ruling party. Anthony Mascarenhas estimates that the number of politically motivated murders in Bangladesh after independence was over 2000 by the end of 1973.

By 1975 this figure reached a staggering 30,000, according to Anthony Mascarenhas! The US Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor reported a higher figure of 40,000 killed by various para-military agencies such as Rakkhi Bahini, Lal Bahini, Sheccha Shebok Bahini which unleashed an unbearable reign of terror killing nationalists and patriotic people without any trial.

The climax of extra-judicial killings was the execution of Siraj Sikdar, the leader of Sarbohara Party. New terminologies, such as “crossfire killings”, “gunfights”, or “encounter killings” were invented to cover-up indiscriminate killings.

The legacy of blood continued even after the fall of the Mujib regime in August 1975. General Zia who assumed power had to deal with coups and counter coups that followed Mujib’s killing. And General Zia himself was killed in a failed coup attempt in 1981.

General Ershad who usurped power in a bloodless coup in 1982 proclaimed an emergency in 1987 to fend off the threats posed to his rule on the nebulous ground of internal disturbance. It is estimated that by early 1988, the security forces extrajudicially killed as many as 38 people to crush the anti-Ershad movement. During the dying days of General Ershad military-civilian rule, the security forces indiscriminately killed scores of opposing political activists.

The Rapid Action Battalion (RAB), created by the government of Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP) ostensibly for curbing crimes, indiscriminately killed individuals suspected of criminal activities. From the commencement of its operation in March 2004 until the BNP left office in October 2006, RAB extra-judicially killed 991 individuals.

The military backed regime that deposed the BNP government in 2007 went to extraordinary lengths in establishing a reign of terror to obviate the possibility of any opposition to its rule. Taking the advantage of suspension of constitution, the law enforcement agencies extrajudicially executed as many as 333 individuals during the state of emergency.

The Hasina’s fascist regime killed at least 2581 individuals extrajudicially between 2009 and 2021. Then we have more than 2,000 who accepted martyrdom and thousands who were variously injured to liberate our country from the tyrannical rule of Sheikh Hasina and India’s hegemony.

The list could even be longer when we also pay homage to those who met the fate of forced disappearances and torture during 15 years of fascist rule.

Perished in silence

Should we forget the estimated 15 lakh (1.5 million) who met premature death within 3 years of victory due to the famine caused largely by the greed of the ruling class?

Should we forget the estimated 15 lakh (1.5 million) who met premature death within 3 years of victory due to the famine caused largely by the greed of the ruling class?

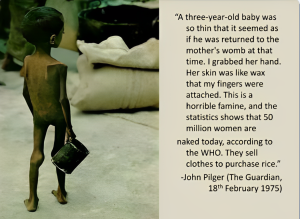

How about an estimated 50 lakh women who stayed naked or half naked as they had to sell their clothes to buy food; or those who had to sell their bodies?

4.5 million people died after the famine due to malnutrition and related diseases.

According to the government, there were only 27,000 famine related deaths!

Those who raised their voices against the misrule of the government were silenced by brutal force using arrests, torture, and extra-judicial killings. Neamat Imam’s famous novel The Black Coat portrays the terrible situation of Bangladesh during the famine of 1974, where Nur Hossain, a protestor against the misrule that created the famine, was killed by Khaleque Biswas, a die-hard supporter o Sheikh Mujib.

In the queue of deaths in silence, we can also add small investors who committed suicide, being robbed by the fascist regime’s cronies who swindled the share market.

Man-made famine – greed

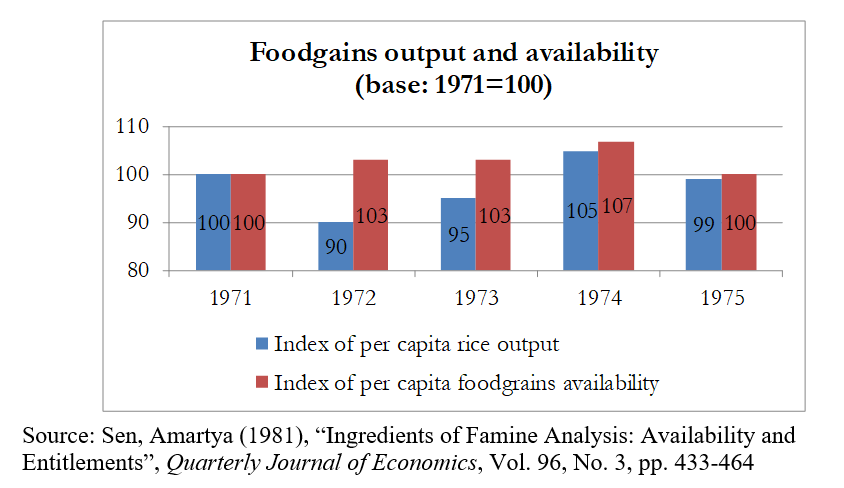

The ruling elite wanted people to believe that the famine was caused by the devastating floods in 1974 that caused food shortages. But the actual figures on food availability tell us a different story.

Food availability on a per capita basis, in fact, was higher in 1974, the year famine struck. In his famous book, Poverty and Famines: An Essay on Entitlement and Deprivation (1981), Professor Amartya Sen concluded: “1974 was the local peak year in terms of both local output and per capita output of rice. Whatever the Bangladesh famine of 1974 might have been, it wasn’t a Food Availability Decline (FAD) famine” (pages 137-138).

Elsewhere, referring to the three famine districts (Rangpur, Mymensingh and Sylhet), Amartya Sen wrote with an exclamation: “Rice production in all three districts went up substantially. So did food availability per head. Furthermore, in terms of absolute food grains availability per head, these three famine districts were among the best supplied five districts in a list of nineteen!” (Quarterly Journal of Economics, Vol. 96, No. 3, page 453).

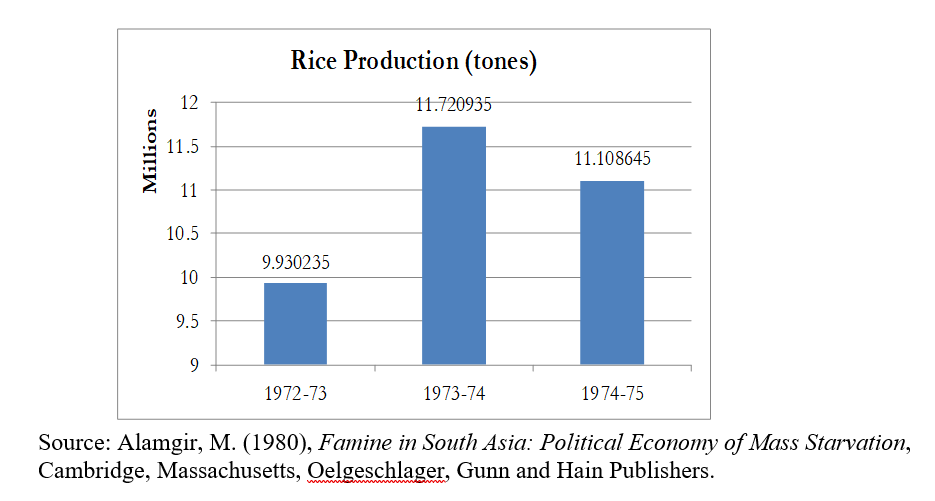

Floods destroyed much of the rice crop of 1974, but rice production during 1973-74 was higher than that in 1972-73. Although rice production was down in 1974-75, it was higher than 1972-73. Yet the famine did not occur in 1972-73; it came in 1974 when food per capita was at an all-time high. Starvation began before the rice that the floods destroyed would have been available. So, what was the problem?

According to Professor Sen, “The main factor would appear to be the rise in prices” (p. 456). He further noted: “inflationary forces operating on the rice market has started pushing rice prices up very sharply much before the floods hit” (p. 458). How was it possible for prices to rise so steeply when food production or total availability of food grains in fact increased?

The experience tells us that this can happen only due to hoarding by unscrupulous business and/or smuggling in connivance with the ruling class. One simply needs to open the pages of newspapers (e.g., Ittefaque) and weeklies (e.g., Weekly Bichittra, The Dhaka Digest or Moulana Bhashani’s Haq Katha) to find out the scale of corruption and smuggling by people well connected with the ruling party between 1972 and 1975. It will be curious to trace the subsequent fortunes of those who became rich at this time. It will not be difficult to see how many of today’s new rich accumulated their wealth at the cost of millions of innocent lives, mostly children.

Man-made famine – policy failure

There was also policy failure. According to Professor Nurul Islam who was the Deputy Chairman of the Planning Commission, there was a severe reduction in public stocks starting at the end of1973 and a drastic reduction in public distribution, especially the modified rationing system and relief distribution, starting in January 1974. This triggered a sharp rise in prices as early as March 1974 and an upsurge in speculative holdings of stocks.

Professor Islam recounts an interesting meeting with General Ziaur Rahman. “During this period, I had an interesting encounter with Zia who was the Deputy Chief of Staff in the army and was involved in supervising the anti-smuggling operations along the borders. He at his own initiative came to see me in my capacity as the Deputy Chairman to discuss his findings or judgment that there was a very large-scale smuggling ranging anywhere from half a million to a million tons. He felt that the Prime Minister was not correctly informed by his political colleagues and officials about the scale of smuggling. Under the circumstances, I should intervene to convince the Prime Minister about the gravity of the situation.” (Nurul Islam, “What was it about the 1974 Famine”, Scholars Journal, https://www.scholarsbangladesh.com/nurulislam1.php).

Professor Islam did not intervene. Although he acknowledged that smuggling was happening, using his economic argument, he did not think it was large enough to cause food shortages or price hikes on such a scale. Instead, he commissioned a study by a visiting Cambridge Professor, Brian Reddaway! It seems like Nero playing his fiddle while Rome was burning!

Unsurprisingly, the Cambridge Professor too came to the same conclusion as Professor Islam, that “smuggling was not significant enough so as to run into hundreds of thousands of tons”.

Postscript

The Awami League polarized politics in Bangladesh along the lines of for and against liberation (independence). But we should be asking who shattered the dream of an exploitation- and corruption-free Bangladesh and who wanted to establish a truly independent, democratic, socialist and secular Bangladesh.

In the euphoria of our celebration of victory, let us not forget over a million victims of a man-made famine and thousands who have fallen due to extra-judicial killings, including those killed in coups and counter-coups.

A revised and extended version of a piece published in The Financial Express (Dhaka), on 26 December, 2013

Anis (Anisuzzaman) Chowdhury, an alumnus of Jahangirnar University and University of Manitoba, is a macro-development economist with close to 100 publications in international journals and two dozen books, including Moulana Bhashani: Leader of the Toiling Masses and Moulana Bhashani: his Creed and Politics. Currently an adjunct professor, he was a professor of economics (2001-2008), Western Sydney University. He served as Director of Economic and Statistics Divisions of UN-ESCAP (Bangkok, 2012-2015) and retired from the UN Headquarters (New York) in 2016 after serving as Chief in the Financing for Development Office. He regularly writes opinion pieces on global socio-economic-political issues. He serves on the editorial boards of several academic journals.