Dr. Ahsan Mansur, the newly appointed governor of Bangladesh Bank, told the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) on Wednesday, August 21, 2024, that the country’s central bank will be raising its policy rate from 8.5% to 9.0%. Moreover, he made it clear that the policy rate will be further increased to 10% or more if necessary, justifying it as an appropriate measure for stifling inflation, which has been high and persistent.

Nominal Policy Rate, Real Policy Rate, and the Fisher Equation

Bangladesh Bank reports that as of July 2024, point-to-point inflation was 11.7%, while the monthly average inflation for the 12-month period was 9.9%.

These data clearly show that the nominal policy rate is still lower than the observed inflation as of July. If observed inflation can be used as a rough proxy for expected inflation, according to the Fisher equation (which states that the nominal interest rate is the sum of the real interest rate and expected inflation), the real policy rate has been negative as of July 2024. Even if the nominal policy rate is raised to (say) 10% in the coming months, which is what Governor Mansur suggested in his interview, as long as the rate of expected inflation stays at (say) 10 or 11%, the real policy rate would be either zero or negative. Will expected inflation decline in the coming months? That remains to be seen. What is Bangladesh Bank’s target for the real policy rate?

While inflation in major advanced countries and most key emerging markets has declined notably since the post-COVID peaks, inflation in Bangladesh is still unacceptably elevated. But would raising the policy rate succeed in curbing inflation if the causes of inflation are structural? There is considerable scope to debate various important questions pertaining to monetary matters and financial stability issues.

It would be interesting to learn what sort of data, research, and empirical findings Governor Mansur and Bangladesh Bank’s research staff furnish to justify the decision to raise the policy rate as the primary means for taming inflation.

Inflation Fighting Strategy Must Be Based on What Drives Inflation in Bangladesh

There are many important questions regarding the central bank’s inflation fighting strategy.

-

- What drives inflation in Bangladesh?

- Why has inflation been elevated and persistent?

- What is the pass through from the exchange rate and import prices to the consumer price index?

- What are the supply constraints and infrastructure bottlenecks that have led to inflation persistence?

- What empirical relationships do nominal wage growth, mark-ups, and productivity have with consumer price inflation in Bangladesh?

- Is there really any solid and reliable evidence that higher (lower) policy rates will reduce (increase) inflation in Bangladesh?

- How effective is the monetary transmission mechanism in Bangladesh?

- What is the central bank’s target inflation range?

- Who decides the target inflation range?

- How much would the policy rate need to be raised to reduce inflation to its targeted range?

- Are the tools adequate to do the job?

- How long would it take to attain the central bank’s inflation target?

- What indicators would the central bank use to assess inflationary pressures and the effectiveness of its implementation of its monetary policy strategy?

- How will the central bank measure inflation expectations among consumers, households, businesses, purchasing managers, professional forecasters, and financial market participants in Bangladesh?

I would like to see the central bank, under its new leadership, address these relevant questions in a clear manner. While definitive answers are hardly ever possible in economics, these matters can be discussed rigorously and should be informed by good data and understanding of the empirical regularities.

Bangladesh Bank needs to have an active research agenda and conduct regular surveys, in conjunction with other agencies, to inform public policy discussions on monetary affairs and financial stability. Bangladesh Bank’s inflation fighting strategy must be based on empirical evidence and a theoretical understanding of what drives inflation in Bangladesh.

Governor Mansur’s Experience Will Be Invaluable

Governor Mansur is an experienced economist with a distinguished professional profile. He was a senior functionary at the International Monetary Fund (IMF), with many years of experience at the Fund’s Washington, DC headquarters. He has also worked extensively with policymakers at the highest level in the Middle East and Asia, and in recent years he has been a leading figure in Bangladesh’s think-tank world. Undoubtedly his IMF experience and deep knowledge of its lending facilities, approach to conditionalities, and institutional politics will prove invaluable for Bangladesh as the country negotiates for additional funding.

Economists in the Interim Cabinet

Following the Monsoon Revolution that led to the downfall of Prime Minister Shiekh Hasina, the interim administration, headed by Chief Adviser Muhammad Yunus, has brought several leading economists into the cabinet. Professor Muhammad Yunus is himself an economist who founded the Grameen Bank; he has been an incisive and tenacious critic of the limitations of conventional neoclassical economics for its failure to eradicate poverty in the real world. Nevertheless, economists in the cabinet of the Yunus-led interim government are scholars and policymakers who are well-versed in mainstream economics.

Dr. Salehuddin Ahmed, a former central bank governor, is the adviser for the important ministries of finance and commerce, has a deep knowledge of the financial system and macroeconomic management. Professor Wahiduddin Mahmud, a distinguished scholar who is now responsible for the key ministries of planning and education, will bring his previous experience in the caretaker (transitional) government and his deep knowledge of Bangladesh’s economy. Dr. Muhammad Fouzul Kabir Khan—a former civil servant with experience in the energy sector, revenue administration, and infrastructure financing—knows the workings of the Bangladesh civil administration inside out; he will now be the adviser responsible for several infrastructure-related ministries, including road transport, bridges, railways, and power, energy, and mineral resources.

Formidable Challenges

While the central bank’s new governor has assembled an impressive team of distinguished economists with vast policy experience and expertise, the challenges that the interim government face are formidable, ranging from elevated inflation, pressures on the country’s foreign reserves, and depreciation of the exchange rate, to cost overruns in large-scale projects and deep-seated problems in the financial sector (including a huge share of nonperforming loans, capital flight, and soft job growth). The list of economic and financial challenges is long, but the Monsoon Revolution has demonstrated the Bangladeshi people’s resilience and unity amid adversity and repression. In the past few decades, Bangladesh has made impressive progress in real per capita income growth, as well as in various human development indicators, such as adult literacy, school enrollment, life expectancy, child mortality, and immunization rates. Lately though, rampant corruption and cronyism, and a rise in inequalities in income, wealth, and opportunities in the final phase of the Hasina regime, started to undermine and stall progress. The low prospects of finding jobs among the youth and rising costs of living, in combination with the regime’s repressive characteristics (including the indiscriminate and illegal use of force), created the conditions for the student-led uprising that brought Hasina regime to its end.

More than Mere Inflation Fighting

The interim government will need to give high priority not just to curbing inflation, but also to creating employment and opportunities, restoring law and order, stabilizing the financial system, and promoting high economic growth. Under current circumstances, the central bank should not be solely focused on its inflation mandate; rather, Bangladesh Bank must take a holistic view of the economy.

Despite claims that inflation is harmful, after extensive research, World Bank’s former Chief Economist, Michael Bruno, and the Bank’s former Senior Economist, William Easterly, concluded, “The ratio of fervent beliefs to tangible evidence seems unusually high on this topic.” They also found that the growth-inflation relationship was driven by extreme cases of hyper-inflation in excess of 40-50%, which are rare.

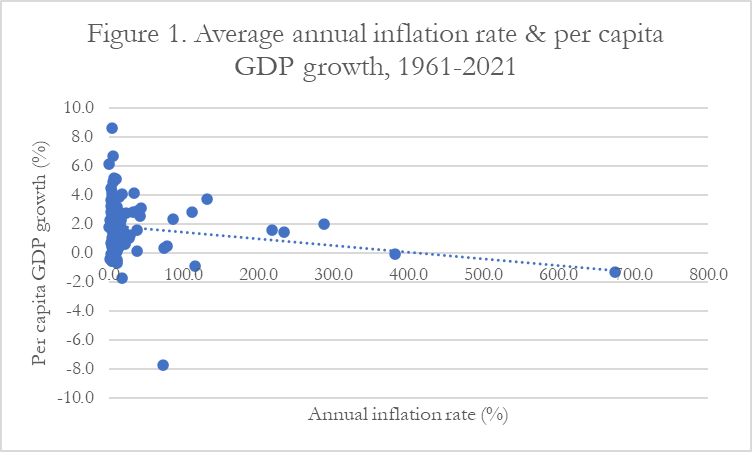

Figure 1 (using World Bank data for 124 developing countries) bears testimony to Bruno-Easterly findings. The seemingly negative relationship between the two is clearly due to a few extremely high inflation cases. For the vast majority of countries, average annual inflation rates over the six decades were below 40%.

Figure 1 (using World Bank data for 124 developing countries) bears testimony to Bruno-Easterly findings. The seemingly negative relationship between the two is clearly due to a few extremely high inflation cases. For the vast majority of countries, average annual inflation rates over the six decades were below 40%.

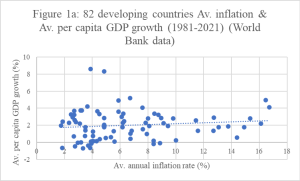

As can be seen from Figure 1a, when countries with average inflation rate above 20% are excluded, the inflation-growth relationship becomes positive. That is, inflation and growth move in the same direction. This has been also the experience of Indonesia, South Korea, Thailand and China during their high growth phase (around 7-8%) when average annual inflation rates were in the range of 11-13%.

As can be seen from Figure 1a, when countries with average inflation rate above 20% are excluded, the inflation-growth relationship becomes positive. That is, inflation and growth move in the same direction. This has been also the experience of Indonesia, South Korea, Thailand and China during their high growth phase (around 7-8%) when average annual inflation rates were in the range of 11-13%.

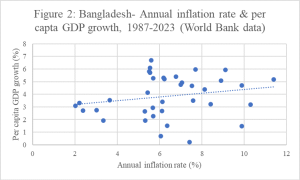

Figure 2 shows that the inflation-growth relationship in Bangladesh has been by and large positive.

Figure 2 shows that the inflation-growth relationship in Bangladesh has been by and large positive.

To summarize, contrary to some popular narratives, the inflation-growth and inflation-poverty relationship is positive as long as inflation remains moderate in the range of 10-20%. Moreover, the correlation between the two variables does not imply causality. This observation is broadly consistent with extant empirical literature on the inflation-growth relationship.

Central Bank Independence

Despite the rhetoric about the “independence” of some central banks in major advanced countries, central banks serve the governments of their countries. Historically, central banks were founded to finance the activities of a sovereign state. At best, central banks can be operationally independent within the government and free from day-to-day politics, but they always act as the government’s bank, clear the government’s checks, and work to ensure that the payment system is operating seamlessly. A central bank’s mandates depend on the legal framework, social contract, and economic institutions and practices in the society they serve. In a democratic system, I firmly believe that Bangladesh Bank must be held accountable to the representatives of the people.

Whilst Bangladesh Bank must do what it takes to curb inflation, as Governor Mansur stated in the BBC interview, a key responsibility will be “cleaning up the country’s banking sector,” which is marred by nonperforming loans thanks to corruption, cronyism, and malfeasance. Governor Mansur is correct in assessing that under the previous regime, dishonest businessmen, some bank insiders, and certain politicians and government officials engaged in a “designed robbery of the financial system.” Under the previous regime, the most effective strategy for robbing a bank was either to own one and/or simply “buy” the politicians and government officials responsible for regulating and supervising financial institutions.

If Governor Mansur and his team at the central bank want to “restructure the banking sector,” their phone lines to the Ministry of Finance will be very, very busy. Governor Mansur stated that the Ministry of Finance will need to inject “$15–10 billion” to recapitalize the banks. This will require Bangladesh Bank to work closely in conjunction with the Ministry of Finance and other government agencies in order to: infuse capital into the financial system; regulate the financial system, financial institutions, and capital markets; ensure the payment system’s smooth operation; manage government debt; realign the exchange rate to support exports and export diversification; and create conditions that promote domestic investment in equipment, infrastructure, intellectual capital, and foreign direct investment.

Monetary-Fiscal Coordination

Bangladesh Bank’s approach to policy should be based on the principles of monetary-fiscal coordination rather than the mantra of central bank independence. The central bank will need to ensure that depositors remain whole, that there is no scope for runs on banks and financial institutions, and that their budgetary stance is expansionary rather than contractionary. The governor told the BBC that the authorities’ “first effort” regarding loan defaulters “would be to try to take people to task and get the money back.” The central bank should hire fancy and clever lawyers that get the job done. Meanwhile, the officials at the Ministry of Law must work with the relevant authorities to reform Bangladesh’s legal system to enact recovery from loan losses. Bangladesh Bank, other agencies responsible for financial regulation, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, and the national police and intelligence agencies must also press the case with overseas regulators and Interpol to bring back stolen money parked in offshore accounts.

Governor Mansur told the BBC that he “expects Bangladesh’s new government to announce a sharp reduction of spending despite the ongoing turmoil.” No doubt that’s exactly what IMF officials would normally seek to extract from countries using IMF facilities. (To be fair, from time to time IMF officials pronounce that they are no longer wedded to orthodoxies.) However, it would be more prudent for the interim government to maintain an expansionary but responsible fiscal policy, allow a moderate depreciation of the currency, and address the structural factors that have led to elevated and persistent inflation. First, monetary tightening may not tame inflation. Second, excessive monetary tightening could derail the interim government’s other important goals if it leads to a slump in effective demand and dampens job growth.

The IMF has special facilities for post-conflict countries. It might be appropriate for Bangladesh to tap into such resources, as pointed out by Jyoti Rahman, an economist and prolific blogger.

Message for Development Partners

It would be appropriate for Bangladesh’s authorities to impress upon the country’s development partners that Bangladesh needs the space for fiscal expansion to address its current problems, structural challenges, and attain higher levels of economic growth and human development. Study after study shows that austerity economics has been not successful. Whilst spending on ineffective and inefficient programs should be reduced, public sector dissaving will enable the domestic sector to save. Therefore, the overall budgetary stance should be expansionary to support aggregate demand, create employment (both in the private and public sector), foster human development and capabilities by improving education and health, build infrastructure, and expand and diversify the country’s export sectors, as the health of the financial sector and banks depends on the growth of domestic economic activity and exports.

Nay to Austerity

Bangladesh should be not subjected to the economics of austerity. During the global financial crisis and the global lockdown, central banks in the major advanced countries and key emerging markets kept their policy rates low, while fiscal policy provided income support and public spending. These central banks expanded their balance sheets during those periods to support asset prices, stabilize the financial system, and revive their economies. Similarly, Bangladesh Bank’s interest rate policy, balance sheet policy, and financial regulation framework should support the interim government’s overall objectives.

Realistically the options for most emerging-market and developing economies that seek assistance from the IMF are, alas, limited. But Bangladeshi policymakers will need to create and demand the policy space to enact reforms that serve the country well rather than serving the coupon clippers, international money managers, and donors.

Comprehensive Reforms

Comprehensive reforms will take time. Thus, in the BBC interview, Governor Mansur indicated that elections would be held in about “three years or more.” That seems fair, though there is considerable scope for reasonable people to ponder on what is the optimum term for an interim government. Whatever it may be, the interim government should quickly outline and initiate comprehensive reform of the country’s financial system. Its aim should be to end the practices that led to the “designed robbery of the financial system.”

Citizens of Bangladesh, the working people of the country, honest businesspersons, and investors expect Bangladesh Bank to enact sound regulations and undertake high-quality supervision of the financial system so that banks and other financial institutions foster lending based on the objective and fair assessment of projects rather than connections and malfeasance.

As the primary regulator of banks and other financial institutions, Bangladesh Bank should not hesitate to take strong legal actions against those who fail to abide by the rules of the game. The central bank itself, too, will need to improve its act. Its operational risk management has been poor, as evinced by the hacking heist of its foreign exchange reserves. Its regulatory oversight and supervision have been abysmal, as evinced by the huge pile of nonperforming loans in the banking system. Bangladesh Bank will need to establish transparency and effective communication, improve its management, and much more. The staff of the central bank will be very busy.

From Hope to Strategy

The Monsoon Revolution has raised hopes. Admittedly, revolutionary hopes are often too hard to meet. Nevertheless, with appropriate policies, an effective strategy, wise leadership, and the goodwill of the international community, the interim government could uplift the country and raise the quality of life for its citizens. Its goals should include creating the conditions for shared prosperity and equality of opportunity. The central bank can play a constructive role in this effort, if its focus is much broader than taming inflation. Its theoretical oeuvre should be multidisciplinary, encompass different schools of thought, and draw upon practical wisdom and experience in policymaking rather than be confined to the dictums of mainstream macroeconomic theory and models. After all, Chief Adviser Yunus did not hesitate to override the dogmatic confines of conventional wisdom when he ventured to set up Grameen Bank and extended credit to women facing the hardships of poverty and destitution.

Bangladesh Bank’s immediate tasks are ensuring financial stability, taming inflation, and bringing discipline to the financial system. It will need to work in collaboration with the Ministry of Finance and other agencies in the spirit of monetary-fiscal coordination to support the interim government’s goals of shared prosperity, human development, and citizens’ freedom.

I wish Governor Mansur and his team at Bangladesh Bank the best of everything.

Tanweer Akram

Tanweer Akram is a financial economist. He has worked for various major corporations and financial institutions including Citibank, Wells Fargo, General Motors, Thrivent, Voya Investment Management, Moody’s Analytics, and Kearney. Acknowledgements: The author thanks Elizabeth Dunn for her copy-editing support and Professor Anis Chowdhury for his suggestions. Disclaimer: Views expressed are solely those of the author. An earlier version of this article was published in: https://nuraldeen.com/2024/08/24/bangladeshs-monetary-policy-monetary-fiscal-coordination-and-the-monsoon-revolution/ E-mail: tanweer.akram@gmail.com