Courtesy: The Business Standard, “Bangladesh drops a notch on corruption index” 25 January, 2022

Bangladesh has emphatically proven the doubters wrong. It achieved remarkable economic growth rates defying all the odds at the time of its birth following ruthless destructions by the Pakistan army. Bangladesh overcame not only internal political upheavals caused by coups and counter coups, following the brutal murder of the founding fathers, but also the most difficult external environment caused by the collapse of the post-World War II international economic governance architecture and two oil price shocks. It also avoided the debt crises of the 1980s that caused two lost decades of development in Latin America and Africa.

However, Bangladesh continues to be one of the most corrupt countries in the world. It was at the bottom of the list of most corrupt countries, scoring 1.3 out of 10 in 2003, marginally above Nigeria (1.4). Its corruption score declined in 2022 , placing it as the 2nd most corrupt country in South Asia. Globally, Bangladesh is ranked 147 out of 180 countries.

Corruption is generally seen as a barrier to economic growth and development. Then how can one explain this enigma – being both a star growth and corruption performer?

Elite bargain

Stefan Dercon, a Fellow of Jesus College at the University of Oxford, attributes Bangladesh’s stellar growth performance vis-à-vis other corrupt countries, such as Nigeria, to ‘elite bargain’.

‘Elite’ is a group of people, large or small, with power and influence. Elite can come from politics, the military or the business community, senior civil servants, public intellectuals and so on.

‘Elite bargain’ is an implicit understanding among the elite about their conduct with regard to economic rent, and how they view the State. It determines “the boundaries of actions, and things they would do or not do, which is a kind of a joint project”. Every society has its elite bargain.

Elites determine the fate of a country as they run or control the key aspects – trade, commerce, civil administration, law & order, judiciary and defence & security. They also dominate politics and legislature, thus design the legal framework – regulations – within which business can or cannot operate and property rights can or cannot be enforced.

In some countries, elite bargain may be “stealing from the people”; in others, the State is largely seen as an instrument to reward a very small group – ethnic or otherwise, instead of the broader population. Such elite bargains are a ‘zero-sum’ game, and corruption is detrimental to growth.

Dercon argues that growth and development need a specific feature of elite bargain that puts growth and development centrally within the actions and behaviours of those people in the elite. In such an elite bargain, various sections of the elite share from a growing pie.

Dercon, however, doubts whether Bangladesh’s current elite bargain will hold or would be good enough to enable the country to transit to the next stage of a more diversified economy. Its dynamism may be stymied by vested interest groups that benefited from the current arrangement. More importantly, its weakened institutions, especially the lack of checks and balance, is likely to be a critical barrier.

Primitive capital accumulation

Corruption is nothing but a means of primitive capital accumulation. In Part VIII of Marx’s famous Das Kapital, (Capital: A Critique of Political Economy), titled ‘So-called Primitive Accumulation’, Marx describes the brutal processes that separated working people from the means of subsistence, and concentrated wealth in the hands of landlords and capitalists. According to Marxist scholar David Harvey primitive accumulation is a process which principally “entailed taking land, say, enclosing it, and expelling a resident population to create a landless proletariat, and then releasing the land into the privatized mainstream of capital accumulation”.

The development of capitalism in Europe and America was preceded by primitive accumulation through criminal, bloody, unethical and inhuman methods domestically and extraction of resources from colonies. Investment of criminally accumulated wealth, particularly from colonies, stimulated the industrial revolution in England. In short, criminality characterises capitalism’s beginning.

Corruption is nothing but a method of primitive accumulation – a means of amassing monetary wealth – in neo-colonial economies by an emerging indigenous capitalist class. Government-business relations – a sanitised terminology for corruption – have been a key factor in the industrialisation of South Korea, Taiwan and even Japan.

Thus, corruption is endemic in almost all newly industrialising countries, such as Nigeria, Indonesia, Thailand and Philippines. Nigeria moved to the 150th spot in 2022, Indonesia fell 14 spots to rank 110th; Thailand is placed at 101 and the Philippines at 116 out of 180 countries on the Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions 2022 list– not very different from Bangladesh’s 147th place.

Elite stake

What puts them apart in terms of growth and development is ‘elite stake’ – how the elites perceive their fate – in the country. If they think that the future of their children lay in their countries then they will invest their ill-gotten money mostly domestically. However, if they think the future lies elsewhere, they will siphon off their criminally acquired wealth abroad. It is pure plunder, no different from colonial extractions.

Between 1970 and 2010, Bangladesh lost 30.4% of its 2010 GDP due to illicit transfer of funds. In a 2011 UNDP report Bangladesh was ranked no 1 among least developed countries in illicit transfer of funds between 1990 and 2008; the cumulative outflow was estimated at US$34.8 billion; it went up to around US$50 billion between 2009 and 2015. In 18 months of Covid pandemic, Bangladeshi nationals have topped real-estate and housing investment in Dubai. Australia, Canada, USA and UK are other popular countries for Bangladeshi elites as their second homes.

The elites of Bangladesh do not have faith in their own country. Thus, we see from the Head of State and Head of Government to the leader of the opposition parties – all prefer overseas for their medical and other, such as children’s education, needs. While the elites rush to acquire a second passport or overseas homes, seek improved treatments – even for minor regular medical check-ups – and send their children to study abroad, the commoners queue in the under-resourced public hospitals and their children study in poorly resources public universities, infested with party politics.

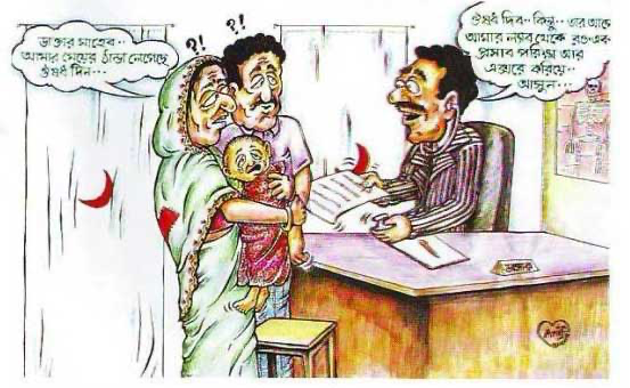

Courtesy: Centre for Policy Dialogue, “Corruption and Healthcare”, 18 October, 2018

Courtesy: Fair Observer, “When Corruption Becomes Oppression in Bangladesh”, 28 May, 2015

One does not see this in the countries which not only grew rapidly despite corruption, but also sustained their progress, such as Taiwan, South Korea and Japan. Even in Indonesia or Thailand, elites built the national system – well-resourced public health and education facilities. This has created trust in the national system. More importantly, this demonstrates that elites have a stake in their countries. And this is one of the main reasons why these countries forged ahead.

Lessons from South-East Asia – Good governance?

Indonesia and Thailand were disease infested poor countries. The Nobel Laureate economist, Gunnar Myrdal, did not have much hope for Indonesia when he published his famous Asian Drama in the late 1960s.

Philippines was much ahead of Indonesia and Thailand in the 1950s. Philippines per capita GNP of US$150 in 1950 was about twice that of Thailand, and during the 1950s; and Philippines recorded the fastest annual GDP growth rate of 6.4% compared to Thailand’s 5.7% and Indonesia’s 3.8%. In the early 1970s, Philippines per capita GDP in purchasing power parity terms were about the same as South Korea’s and above that of Thailand.

Yet, Philippines fell behind other South-East Asian countries since the mid-1970s. Many have attributed the failure to progress to the lack of good governance or the prevalence of widespread corruption. However, this thesis of ‘good governance’ or absence of widespread corruption cannot explain South-East Asia’s phenomenal progress.

Indonesia or Thailand is not less corrupt than Philippines. In fact, in 1995, Philippines was ranked above Indonesia which was at the bottom of the list of corruption perception index (CPI); Thailand was only 2 positions above. In 2013, Philippines moved up the scale to be placed 8 places above Thailand and Indonesia still remained at a lower level. Yet, both Indonesia and Thailand have beaten Philippines in economic growth.

Two other interesting cases from the region are China and Viet Nam. In 1995, Philippines was ranked 4 places above China which was the second last, just above Indonesia and in 2013, Viet Nam’s position was 22 places below Philippines. Both China and Viet Nam are the two fastest growing economies in Asia!

So, what explains this apparent anomaly – fast economic growth despite poor corruption ranking? One possible answer is ‘elite stake’. When elites believe that they have a stake in the country, they invest their ill-gotten money in the domestic economy. In this case, corruption is nothing but primitive capital accumulation – when invested, it contributes to economic growth. However, it may worsen income distribution.

This was what happened in Philippines when the Philippino elites began to think that their future was in the United States. This, of course, coincided with Marcos’ usurpation of power in a coup. Global Financial Integrity (GFI) 2014 report shows that an estimated US$132.9 billion flowed illegally out of Philippines between 1960 and 2011.

Sustaining progress

Courtesy: BDneww24.com, “Hoping for a corruption-free Bangladesh after the pandemic”, 15 March, 2023

The lack of a tight relationship between corruption and economic growth does not mean that we should give up the fight against corruption and not demand good governance. They must continue; but will not be sufficient to usher in a new era.

Furthermore, continued corruption and leakages of funds are detrimental to the sustainability of growth and progress. Malaysia is a clear example, being in a ‘middle-income trap’. The tale of 1 Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB) is one of brazen outright theft and corruption – perhaps the largest in the world. Between 2009 and 2015, US$3.5 billion was lost from Malaysia’s self-styled development company allegedly through theft, bond mispricing and overpayment for assets. GFI’s 2012 report placed Malaysia among the top 10 sources of illicit transfer of funds globally.

Illicit financial flows (IFF) from Bangladesh were 36% of its total tax revenue in 2015, according the UNCTAD’s LDC Report 2019. Bangladeshis are named in the infamous Panama and Pandora Papers of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists. Huge amounts of money, swindled from banks through fraudulent loan schemes, found their way overseas, including the recent incident involving Islami Bank and its directors that threatened the collapse of the financial sector.

Nationalism and economic progress should be closely linked. One of the reasons we fought against colonialism was to take control of our own destiny; aspirations for progress were the driving force for the masses to rise and unite against colonial powers.

Unfortunately, Bangladesh remains divided in defining nationalism even after 50 years of independence. Are we Bangali or Bangladeshi? While political leaders debate and accuse the opponents for lacking patriotism or harbouring “anti-liberation spirit”, the elite continue to rob the nation and transfer their loots to their dream countries. “A fish rots from the head down”. Our leaders need to give the right signals. They must demonstrate confidence in the national system which is used by the commoners. They must rebuild the institutions and strengthen checks and balance. They must unite the nation around national visions as it was done for achieving impendence. Only then can we regard them true leaders who can inspire the people to work hard to fulfil their dreams and achieve inclusive and sustainable progress.

Anis (Anisuzzaman) Chowdhury, an alumnus of Jahangirnar University and University of Manitoba, is a macro-development economist with close to 100 publications in international journals and two dozen books, including Moulana Bhashani: Leader of the Toiling Masses and Moulana Bhashani: his Creed and Politics. Currently an adjunct professor, he was a professor of economics (2001-2008), Western Sydney University. He served as Director of Economic and Statistics Divisions of UN-ESCAP (Bangkok, 2012-2015) and retired from the UN Headquarters (New York) in 2016 after serving as Chief in the Financing for Development Office. He regularly writes opinion pieces on global socio-economic-political issues. He serves on the editorial boards of several academic journals.