After separating itself from Pakistan and emerging as an independent state in 1971, Bangladesh has come a long way, since.

During the last five decades, Bangladesh has transformed itself from an economically battered country – late and not so lamented Henry Kissinger once contemptuously branded Bangladesh a “basket case” – to a vibrant economy. (See articles by Muinul Islam, “Bangladesh’s fifty-second Victory Day anniversary: Major achievements in this issue and by Anis Chowdhury, “From a basket-case to a middle-income country”, in Vol. Issue 1).

Indeed, during this period, Bangladesh has progressed economically and made vast improvements in health, sanitation, and education and in poverty alleviation. At the time of independence, Bangladesh’s per capita income was US$134 which peaked at around US$2,800.0 in 2020 (in PPP terms US$7,044 per capita) has since fallen to US$ 2528.0 in 2023.

Bangladesh’s GDP growth rate has averaged 6% per annum during the past decade which peaked at 7.9% per annum in 2019, fell to 3.4% per annum during COVID 19 pandemic which since has risen to 7.3% per annum during 2020-2021.

A combination of factors contributed to this stellar performance. These includes the shift from socialistic to market oriented economic policies in 1976, prioritization of poverty alleviation as key goal of development, significant public sector investments in social development, and in agricultural research and modernization, and infrastructure development etc. undertaken by all the governments and more so by the current government, as well as entrepreneurship of the private sector and significant pro-poor innovative initiatives of the non-government organizations (NGOs). More importantly, the sweat and toil of the hardworking people of Bangladesh have combinedly helped the country to progress to where it is today.

However, and notwithstanding these impressive accomplishments in development where every government played a key role, each of these governments and more so the current government has also engaged in taking steps that have contributed to dent democracy and good governance norms that since piled up as what I call ‘Constants of Bad Governance’ (CoBGs) that are a source of grave concern.

Constants of Bad Governance

‘Constants of Bad Governance’ (CoBGs) implies repeating and accumulating, in one form or the other, bad and/or predatory governance practices which have been occurring in Bangladesh since its very inception and have worsened since 2009.

I argue that Bangladesh’s CoBGs have reached a stage where these are threatening to undo if not reverse the gains the country has made in the last five decades. To appreciate the nature of threats the CoBGs pose to Bangladesh, it is important to understand the shapes and forms the CoBGs take.

The CoBGs in Bangladesh have expressed themselves in myriad ways, especially in the following forms:

-

- Democracy backslides

- Governance missteps

- Political othering

- Human rights violations

- Politicisation of public institutions and weakening of public accountability

- Demise of decency in political discourse, and

- Politicisation of education institutions

Furthermore, it is also important to note that each of the elements of CoBGs are inter-connected, meaning that one misstep triggers the other and vice versa and among these missteps, democracy and governance backslides contribute most to other aberrations and abuses.

Political evolution and the chronology of CoBGs in Bangladesh

Indeed, Bangladesh’s tryst with democracy and democratic governance has been anything but inspiring. From 1972 to the present, Bangladesh has experienced following governance forms and practices:

-

- Parliamentary democracy (February 1972-August 1975)

- One-party Authoritarian rule (March–August 1975)

- Military coup and gruesome murder of the Father of the Nation, his family members and colleagues and a period of anarchy and instability (August–December 1975).

- Military dictatorship (January 1976–December 1977).

- Quasi-democratic/military rule (January 1977–March 1990).

- Parliamentary democracy (January 1991–December 2006).

- Civil/military Care-Taker Government (January 2007–December 2008)

- Parliamentary democracy (2009–13)/scrapping of the neutral election-time Caretaker Government (CTG) system; and

- Hybrid democracy (2014- ), meaning rigged elections and continued hold on power, freedom curbing laws, stifling of freedom of expression, repression and suppression of dissents that demonstrate the hallmarks of ‘fascism’.

Sadly, some of these happened, e.g., the transition from the parliamentary democracy to a one-party authoritarian rule in 1975 and the scraping of the election-time Caretaker Government in 2009, without the mandate of the people.

It is clear from the above chronology of governance practices that except for a very brief period, 1991-2006, when Bangladesh practiced functioning parliamentary democracy, the country has suffered numerous democracy and governance setbacks throughout its history. In other words, the CoBGs have been a regular feature of most governing characteristics and the CoBGs included but not limited to interventions such as, the use of democracy to kill democracy and lately, political othering through the promotion of hate politics, the enactment of freedom curbing laws and human rights violations, and the demise of decency in political discourse etc.

Use of democracy to kill democracy

Since its inception, Bangladesh has witnessed twice, the unique and sad phenomenon of the use of democracy to destroy and/or minimize democracy: once in 1975 when the ruling party, the Awami League used its two/third plus majority in the parliament to shift the governing arrangement from parliamentary democracy to a one-party (BAKSAL) system and, more recently, in 2009 and again at the initiative of the ruling Awami League which had two/third majority in the parliament, the abolition of the election-time neutral Caretaker Government (CTG) system that until then successfully delivered free and fair elections in the country.

On both occasions, it is the democratically elected Awami League Government that initiated these democracy cubing actions using democracy which meant that they used their two/third plus majority to initiate change of a fundamental aspect of governance for which the elected representatives had no mandate. A military coup in August 1975 abolished the one-party system and introduced in the country a quasi-democratic/military rule, lasting a decade and a half.

Ironically, the Awami League scraped the CTG system which itself once demanded and got installed, and benefitted by winning the 1996 election. The CTG had consistently produced free and fair elections resulting in a change of government in 2001. It is thus no miracle that since the abolition of the CTG system in 2009, Awami League has not ‘lost’ a single ‘election.’

Political othering and fracturing of the society

Another hitherto less discussed but an ominous feature of governance of the current governing period of the Awami League is the promotion of hate politics as a tool of political othering of the opponents through the invocation of a political mantra called, the “Chetona” (the so-called spirit of liberation). “Chetona” classifies, albeit falsely and maliciously, citizens into two groups, the “Chetonadharis,” the custodians of the spirit of liberation and these include the ruling Awami League and their supporters and the anti-Chetonadharis, the “anti-liberationists,” meaning those who oppose the Awami League.

Naya Paltan area turns into a battleground amid clashes between police and BNP men on Saturday, October 28, 2023. Courtesy: Dhaka Tribune.

More ominously, by dividing people into so-called liberationists and anti-liberationists, the ruling party seems to have attempted to give itself the moral legitimacy to rule as they wish and, flout democratic norms and repress and suppress the opposition, as they will. Furthermore, the Chetona mantra which is also promoted by the ruling party as a secularist ideology and as an anti-dote to the opposition’s Islamist nationalism, is often cloaked in the Islamophobe garb that seeks to re-orient Bangladeshi identity by distorting and, in some cases, by demonizing Bangladesh’s Muslim heritage and its Islamic norms and practices. For example, in recent times, government attempted, albeit unsuccessfully, to change the school curriculum by portraying Muslim rulers of the sub-continent as outsiders and invaders and Islamic/Muslim norms and behaviour, alien to the Bengali culture.

In this regard, what is interesting, if not disturbing to note, is that these very ascriptions of Muslims/Islam as invaders and polluters of the local culture are exactly what India’s ruling party, the BJP’s anti-Muslim Hindutva policy is endeavouring to promote in India to socially stigmatize and economically and politically marginalize the Muslims, the minority in that country. In this regard, it is important to mention that there are credible suggestions that the ruling party, the Awami League relies on Modi government’s support, covert and overt, to stay in power.

In sum, the invocation of the present governing period’s Chetona mantra in political discourse, a tool of hate politics, has sharply divided the people of Bangladesh into two feuding groups—the self-proclaimed ‘pro-liberation’ group, meaning the ruling party, the Awami League and its cohorts and the so-called ‘anti-liberation group’, the opposition, especially, the Islamist nationalists. Such divisions are bound to affect Bangladesh’s evolution into a strong nation with a common set of values of culture and heritage.

Freedom Curbing Laws of Repression/Suppression of Dissent: the 2018 Digital Security Act In October 2018, the AL Government introduced a new Digital Security Act (DSA), which it frequently uses to suppress and punish free speech. Since the adoption of this draconian law, the law enforcement agencies have filed cases against two thousand government critics especially those who criticise government in the social media; many have been taken into custody and been subjected to physical torture, and that some of these detainees have since died during interrogations.

According to a recent newspaper report (Manajamin, May 23, 2023), during 2009–present, the government has filed 111,567 cases in which 3.9 million activists who belong to the Bangladesh Nationalist Party (BNP), the ruling party’s arch-rival, have been accused, are now facing court.

Police escort the photographer Shahidul Alam outside the chief metropolitan magistrate court,

On 30 March 2023, the Chairman of the UN Human Rights Commission, Ambassador Nazhat Sameem Khan, has expressed her concerns about the Digital Act and its arbitrary applications, saying: “I am concerned that the Digital Security Act is being used across Bangladesh to arrest, harass and intimidate journalists and human rights defenders, and to muzzle critical voices online.”

In the context of the above many thus argue that given that the extrajudicial killings, forced disappearances of political dissidents and journalists and frequent incarcerations, and torture of dissidents by the law enforcement agencies have become regular features of governance where arbitrary application of the Digital Security Act to arrest and harass critics are common, make Bangladesh look more like a “fascist state”.

Demise of decency in political discourse

Another worrying trend especially during this governing period, has been the demise of decency in politics. In recent times, the use of disrespectful language by political leaders against their opponents, critics and/or adversaries, real or imagined, has been on the rise, and been compromising the minimum standard of civility in political dialogues. The leader of one political party seems to enjoy a monopoly in bad manners and has set a new low in political conversations.

For example, at the inauguration of the Padma Bridge in May 2022, a momentous event by any measure, the Prime Minister took ugly and distasteful swipes at her political opponent, the former Prime Minister Begum Khaleda Zia, and the Nobel Laureate Professor Muhammad Yunus, the inventor of the universally acclaimed microcredit concept, whom she blames without evidence for the cancellation by the World Bank the Padma Bridge loan on allegations of corruption and kickbacks.

During the opening event when the Prime Minister should have been magnanimous and inspiring, she chose the occasion to do the opposite. She said, as punishment for his (Yunus’) alleged “involvement in the cancellation of the World Bank loan”, he “should be plunged into the Padma River twice, just plunged in a bit and pulled out, so he doesn’t die, and then pulled up onto the bridge. That will teach him a lesson.”

Nobel laureate Muhammad Yunus, along with his lawyers, appears before a Dhaka labour court. Courtesy: New Age

Such indecent swipe especially at the Nobel Laureate Yunus outraged the international community so much that 40 world leaders, as diverse as businessman Richard Branson, musician Bono, former US Vice President Al Gore, former UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon, and former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, wrote an open letter to the Prime Minister in The Washington Post where they expressed their “deep concerns for Professor Yunus’ well-being” and said that “It is painful to see Professor Yunus, a man of impeccable integrity, and his life’s work unfairly attacked and repeatedly harassed and investigated by your government.” The leaders hoped that the government would “allow him [Yunus] to focus his energy on doing better for your country and for the world, rather than on defending himself.”

This must have been one of the saddest moments for Bangladesh and a new low in the annals of hate speech anywhere in the world. More so because when the leader of the country does not respect country’s respectables and honour the honourable, whatever gains that country has made in GDP terms do not compensate the moral loss the society has been inflicted with.

Factors that contribute to the CoBGs

Several factors but more importantly, the governance characteristics meaning attitudes, norms and behaviour of the governing leader and his/her team influence the quality of governance in a country most.

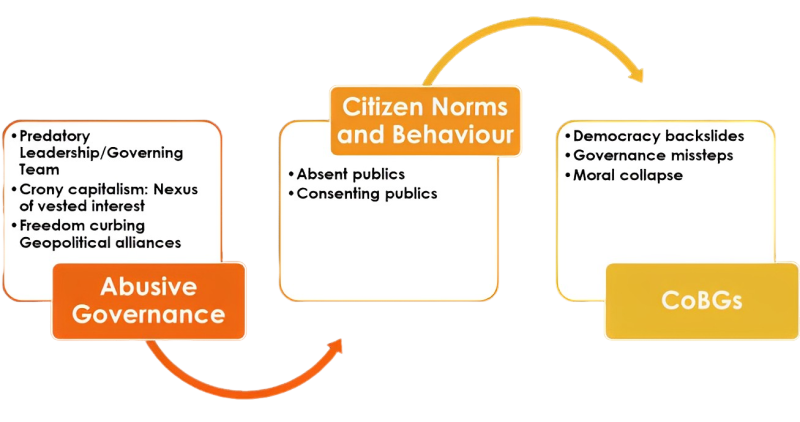

CoBGs would occur if the governance characteristics of the governing leader and the team prioritize stay-in-power over equitable wellbeing of citizens and in the process, entrench control on the one hand, through abusive governing arrangements and on the other, through patronage distribution within and abroad.

Furthermore, CoBGs, also occur and accumulate, and this is important, because of the way citizens respond to governance missteps. There are two types of citizenship behaviour that allow CoBGs to occur and these are: (i) absent publics meaning citizens who are either too intimidated to protest against or resist wrongs or those who look the other way; and (ii) then there are these third category of citizen behaviour and this contributes most to the CoBGs and these are the consenting publics who endorse everything and anything, right or otherwise, that their preferred government/leader does and/or indulges in.

In the context of Bangladesh, this figure shows the close relationships between “Governance Characteristics’ promoted ‘Abusive Governance’ and how the supportive ‘Citizen Norms and Behaviour’ (‘absent and Consenting Publics’) contributed to the CoBGs.

Figure 1 shows the interlinking relationships between governance characteristics, citizen behaviour and CoBGs

Casualties of CoBGs

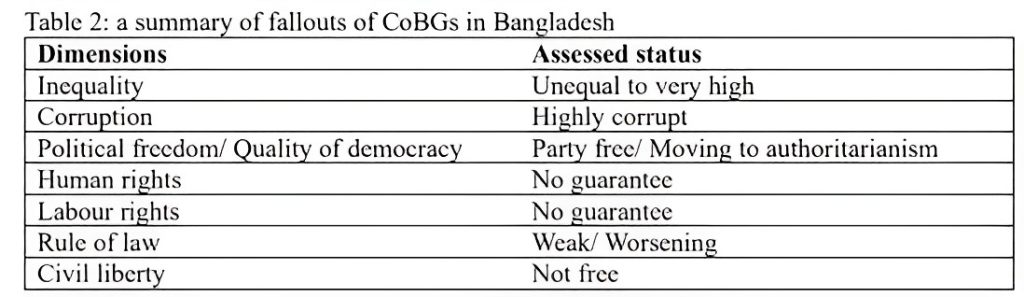

In Bangladesh, the cumulative CoBGs have shrunk democratic space, promoted abuse with impunity and fractured the society. Among these, a major outcome of CoBGs has been depletion of public accountability and the rise of corruption in the country.

Corruption

Corruption has been a lingering scourge in Bangladesh since its inception in 1971 and thanks to the deepening CoBGs, corruption has worsened.

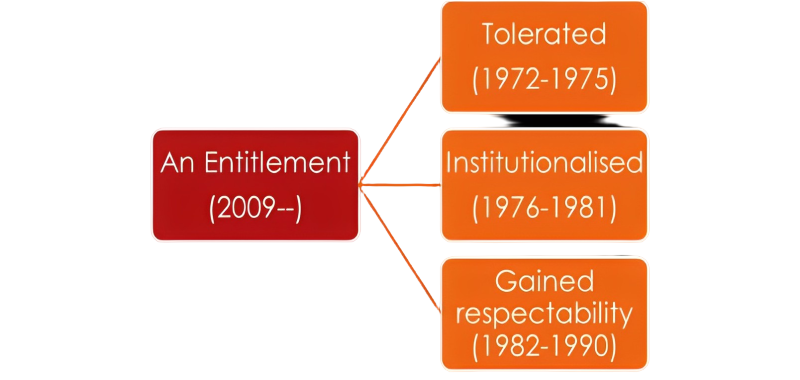

Initially, corruption was tolerated, then it got institutionalized, then corruption gained respectability and in recent years, aggressive politicization of public institutions and curbing of free speech that have depleted the integrity and accountability aspects of public governance, have made corruption an entitlement in Bangladesh.

Figure 2 shows the trajectory of corruption in Bangladesh during 1972-2022, making it an “entitlement”.

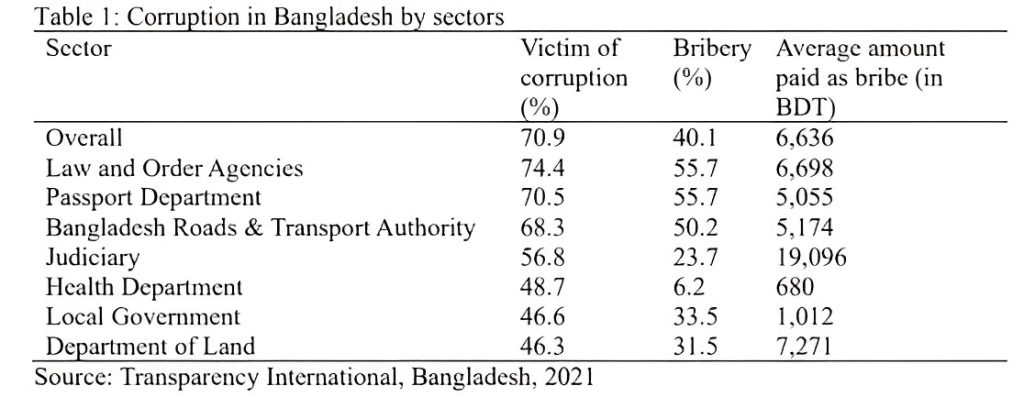

Table 1 reveals the spread and depth of corruption by sectors as it became an entitlement in contemporary Bangladesh.

In this regard it may also be pointed out that the wholesale embrace of the neoliberal economic system—a deregulated corporate-dominated crony capitalist system, the crony capitalism — that promoted the rise of a powerful and opportunistic nexus of vested interest has also played a role in usurping the political system and in the process. This enabled self-seeking policies in conditions where checks and balance are at their minimum and a system that has made institutional deference to abuse a norm. This, in turn, has since contributed to conditions where loot and plunder of national resources as well as rent seeking are routine matters that are often done at the expense of citizen rights including labour rights and wellbeing, wellbeing of the environment, and the society.

In fact, crony capitalism and repression are two sides of the same coin. These intertwining features of the neoliberal economic system promote on the one hand, economic growth through patronaged capitalism and on the other, dent democracy, destroy democratic values and weaken accountability and these, in turn, promote corruption, loot and plunder and legitimise repression in the name of economic growth.

Falling quality in education

Another casualty of the CoBGs in Bangladesh is the falling quality in education. In recent times, aggressive politicization of educational institutions, where loyalty has taken precedence over quality in teacher recruitment and promotion, and where sycophancy overrides scholastic endeavour have severely damaged the quality of education in all institutions. Unfortunately, this includes Bangladesh’s premier education institution, the Dhaka University which once was known as the ‘Oxford of the East’, was ranked in 2022, at 1,816th by the World University ranking, globally that revealed the extremely poor education standards of the country’s tertiary education institution.

Quality of education at the elementary level is no better either. UNESCO, in its 2018 annual report, ranked Bangladesh 120th of 160 countries, slightly above Togo, Timor-Leste, and Nepal and below the Republic of Congo and Uganda.

These falling trends in educational quality are worrisome, as Prosper Dzitse, a lecturer at a South African University once reminded: “Collapsing any nation does not require use of atomic bombs or the use of long-range missiles; it requires lowering the quality of education.”

If the current trends in poor quality in education continues, Bangladesh may very well see itself categorize itself as a nation which is collapsing.

Fortunately, ill-motivated efforts by the education reform advisory committee to distort and downplay Muslim history and heritage, and to caricature Muslim norms in school history textbooks have been less successful. Nevertheless, is no less concerning.

Source: Various international reportsThe Looming CrisisThanks to the mounting CoBGs, Bangladesh’s impressive economic performance and its social harmony are now under threat. In recent times, the CoBGs have multiplied manifold, and have infected the body politic of the society so deeply that these governance aberrations are fracturing harmony and causing despair among people.

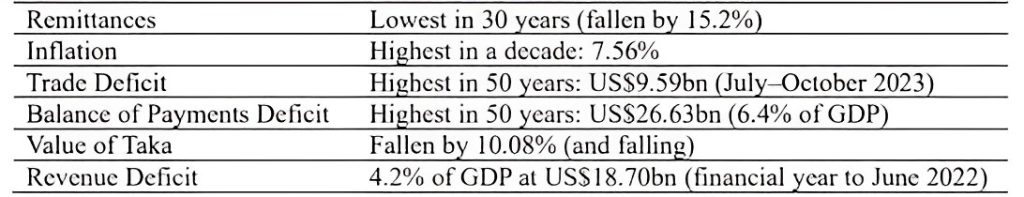

Years of governance missteps and democracy backslides namely, accountability deficits and rise of corruption and reckless spending, loot, wastage of public resources on prestige projects and, lately, the CODID 19 and Ukraine war induced economic stress present a grim outlook, a looming crisis in the horizon, as Table 3 indicates.

Table 3: The looming economic crisis

Table 3 portrays a depressing picture. A recent study suggests: “the [Bangladesh] economy is facing challenges on multiple fronts such as rising inflation, balance of payment deficit along with a budget deficit, declining foreign exchange reserves, contraction in remittances, a depreciating currency, rising income inequality and the demand-supply imbalance in the energy sector. Now added to these challenges is the ailing banking sector crippled by loan defaults i.e., non-performing loans. Bangladesh is particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change.”

The 2023 World Happiness Report has downgraded Bangladesh 24 notches from last year, placed it at 118th out of 137 countries. This is an indication that country’s impressive GDP growth has not benefitted people equitably, and many are unhappy with wealth accumulation by few who acquired their wealth allegedly, not always by fair means and thus many feel left out and depressed.

The duality of impressive GDP and not so impressive CoBGs have made Bangladesh look more like a beautiful house which is also termite infested, where the latter is steadily proliferating and waiting to devour and bring the entire edifice down, one day.

One may recall, Pakistan broke at the height of its economic glory, celebrating the United Nations Frist Decade of Development (1961-1970). Indonesia, too, implored in 1997, after posting three decades of high growth.

The way forward

At one level, Bangladesh is a miracle. It has transformed itself from an “international basket case,” to a thriving economy and from a lethargic society with little to aspire to or dream about, into a vibrant nation filled with ambition and possibilities.

Sadly, the creeping and accumulating CoBGs have reached a level where democracy is a misnomer, human rights are an anathema, public institutions are broken, public accountability is non-existent, free speech is a risky endeavour, corruption is an entitlement, abuse is the norm and decency, and ethics are on decline. Indeed, the CoBGs are threatening to undo the gains the country has made during the past five decades.

The situation is concerning.

Resets are needed urgently to remedy the ills of CoBGs and rescue the Bangladesh and set it on a governance path which is democratic, transparent, and accountable and on a development trajectory which is equitable, sustainable and more importantly, morally nourishing.

This article is an abridged version of the author’s recently published book, Bangladesh’s Seven Governing Periods, 1972-2022: Accomplishments, ‘Constants of Bad Governance’ and the Much-Needed Resets; Publisher: South Asia Journal ISBN 978-0-9995649-2-9 Hardcover; 185 pages; Price: US$ 28.00; BDT 750. To order the book, please email: info@southasiajournal.net

M. Adil Khan

M. Adil Khan is an adjunct professor at the School of Social Sciences, University of Queensland (Australia). He was Chief of Socio-Economic Governance and Management Branch of the Division for Public Administration and Development Management, the United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs (UNDESA), New York until 2008 when he retired from the United Nations. Adil Khan possesses more than 35 years of working experience in international development. His varied job experiences in ‘development’ include but not limited to public policy manager the planning ministry of Bangladesh (1973-1988), consultancies for international aid agencies such as the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and the United Nations, research director on sustainable development at the University of Queensland, senior development advisor of UN in Myanmar and Sri Lanka and senior policy manager at the Department of Economic and Social Affairs, United Nations HQs. His core expertise includes but not limited to public policy, pro-poor development and participatory governance. E-mail: adilkhan1946@gmail.com