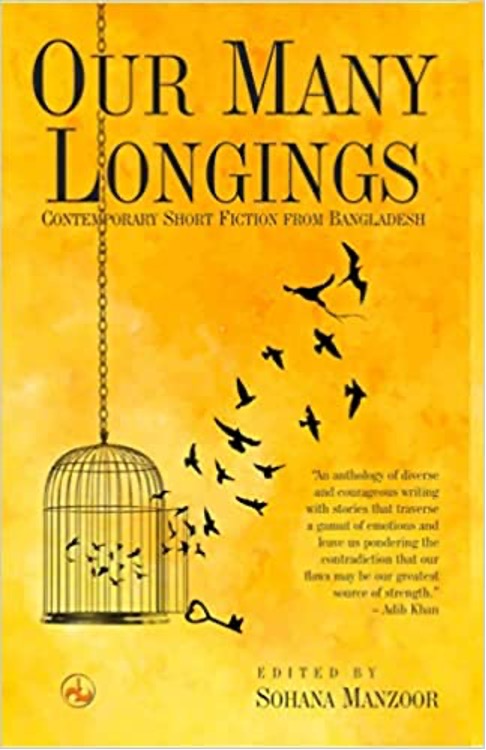

Manzoor, Sohana. Our Many Longings: Contemporary Short Fiction from Bangladesh. Odisha, India: Dhauli Books, 2021. xv+234 pp. ISBN: 978-81-9545604-8.

Our Many Longings is a collection of nineteen Bangladeshi short stories by writers emerging and established, living at home or abroad and using English or Bangla as their creative medium. Bangladesh is a relatively new country, having found its independence only in 1971, after a protracted colonial rule, first by the British and then by Pakistanis, and this book aspires to celebrate its vibrant, variegated life and culture on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary as a sovereign nation: its joys and sorrows; lights, shadows and colours of everyday life; its push and pull between modernity and tradition; its class, gender and inter-religious struggles and, above all, its terrifying but glorious history associated with the War of Liberation, in which, by some estimates, about three million people died at the hands of the brutal Pakistani forces, and about two hundred thousand women were subjected to sexual assault. The book allows us to vicariously experience the country’s social-political-cultural history as well as its living soul; and the loss and longings of those who have left the home soil to build a “nest” elsewhere. We feel the pulse of the country or its immigrant communities as we turn the pages of the book.

Of the nineteen stories in the anthology, twelve were written originally in English, seven by those still domiciled in Bangladesh and five living in the diaspora. The remaining seven stories were written in Bangla, the country’s national language, and translated into English for this book by various hands, including one by the volume’s curator and editor, Sohana Manzoor, an accomplished writer in her own right and the current literary editor of the nation’s pre-eminent English online and print newspaper, The Daily Star.

Although all the stories in the volume are engaging and stimulating, some have greater immediacy and intensity than others. They read more spontaneously and capture the imagination of readers with their simplicity, ingenuity and precision. These are the stories in which the writers have held back and exercised restraint – as all writers should, in the opinion of Kurt Vonnegut – rather than unnecessarily turning and twisting their plots. These include Rahad Abir’s “Beauty and the Jinn,” Shaheen Akhtar’s “The Green Passport,” Tahmima Anam’s “Mother’s Milk,” Dilruba Z. Ara’s “Light,” Afsan Chowdhury’s “Torso,” Kaiser Haq’s “The Emperor’s New Clothes,” Hasan Azizul Huq’s “Without a Name, Without a Tribe” and Manzu Islam’s “Catching Pheasants.” Some of these stories are also thematically profound and, implicitly or explicitly, show us to make the world a better place by shunning greed, lust, selfishness, violence and venom or by overcoming sectarianism, cultural parochialism and religious orthodoxy so that members of society can live in justice, mutual empathy, fellowship and peace.

Abir’s “Beauty and the Jinn” is a striking story about a paedophilic religious teacher who rapes and impregnates an eleven-year-old girl inside a mosque and later blames her as possessed by evil spirits. This is how patriarchy weaponises religion to sexually abuse women or even vulnerable juveniles like Beauty. Society’s tendency to mistreat and muzzle women is also the subject of “Mother’s Milk” and Razia Sultana Khan’s “Decoy.” In “Mother’s Milk,” a young woman suffers from overwhelming guilt for accidentally suffocating her newborn child while breastfeeding him and, concurrently, is forced to bear society’s stigma for the misfortune. In “Decoy,” yet another girl of Beauty’s age, Mukul, is about to be trapped for sexual abuse by a pseudo-religious elderly figure in the family, Babumama, who had previously raped Mukul’s mother.

“Torso” and “Without a Name, Without a Tribe” are gruesome stories about the atrocities committed by the Pakistani army during the country’s Liberation War, in which Bengalis were killed and raped indiscriminately by their Muslim West Pakistani counterparts in the name of saving Islam. Conversely, “The Green Passport” demonstrates how Bengali ultra-nationalism became a source of tyranny for the minority Bihari community in the country after independence, only because they spoke a different language and had supported the Pakistani cause during the war. Another story that pivots on the nationalist theme is Khademul Islam’s “Cyclone”; in this story the author depicts how the callous response by Pakistani rulers to the 1963 tropical storm in Chittagong signalled the growing rift between the two wings of Pakistan and their subsequent secession.

Dilruba Z. Ara’s “Light” and Manzu Islam’s “Catching Pheasants,” as well as Fayeza Hasanat’s “Frank and Frida” and Nadeem Zaman’s “Next Door,” are stories by writers of the Bangladeshi diaspora who continue to write about their home culture or about those who live in displacement and alienation in their host lands. Set respectively in Bahrain, the UK and the US, these four stories predominantly deal with the loss of or quest for identity, as well as the existential rootlessness and multiculturalism, of Bangladeshis (or South Asians, as in “Light”) who have espoused an exilic life of their own volition. Rizia Rahman’s “Petrea” is also about identity, but this story is set in Bangladesh and recounts the psychological dilemma of a young girl, Bindi – the child of an interracial marriage between a British White boss at a Bangladeshi tea garden and his “coolie” female worker – who, after the death of her mother and departure of her father, fails to make sense of her hybrid state and relate to either side of her hyphen. Kaser Haq’s story, however, does not fit any of the discussed categories. A poet known for his caustic wit and wry humour, Haq satirises Asia’s wholesale claim to spirituality and mysticism and postcolonial critics’ tendency to build their career by capitalising on the discourse of writing back to the West in his terse and tongue-in-cheek story.

Three other entrancing stories in the book are Kazi Anis Ahmed’s “Ramkamal’s Gift,” Mojaffor Hossain’s “After Breaking News” and Syed Manzoorul Islam’s “Alter Ego.” “Ramkamal’s Gift” is about a seemingly fraudulent and questionable writer who promises big but disappears before delivering on his promise; however, his charming personality rubs off on several of his followers, who continue with his mission after his disappearance. This character is somewhat reminiscent of Rabindranath Tagore’s Mahendra, a self-adulatory pseudo-writer in the short story “The Professor,” and Saul Bellow’s conman, cryptic psychologist, Dr Tamkin, in Seize the Day. “After Breaking News” is a post-Trump, post-truth story about how the media peddles fake news to often overshadow the truth. It’s about a famous Bengali writer who fails to convince his family and friends that he is alive and well when the media starts wrongly propagating that he has died in a bus accident. Finally, “Alter Ego” is a psychological story about two people, a lawyer and a criminal, who remain involved in a fierce brawl after the lawyer successfully convicts the criminal, until it becomes evident that the two are but each other’s shadows or doppelgangers.

This anthology brings together an excellent array of short stories with a wide range of themes and characters. Collectively, they offer an authentic slice of Bangladeshi life, history and culture, both at home and wherever Bangladeshis have travelled in search of a better life. The stories, including those translated from Bengali, read effortlessly and elegantly, and I would recommend the title to anyone interested in Bengali, Bangladeshi or South Asian literature and culture.