In December 2022, a major breakthrough took place at the United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15) in Montreal, Canada, which set a global agenda to transform humanity’s relationship with nature. The agreement is named The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, (KMGBF) or simply GBF. GBF replaced the Aichi Targets by setting 4 goals for 2050 and 23 targets for 2030.

The Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework envisaged a world where humans will be living in harmony with nature, and “by 2050, biodiversity is valued, conserved, restored and wisely used, maintaining ecosystem services, sustaining a healthy planet and delivering benefits essential for all people”. Target 3 of the GBF aims to conserve and manage 30% of the Earth’s terrestrial, inland water, coastal and marine areas by 2030. The framework proposed that such a target could be achieved through ecologically representative and well-connected systems of protected areas (PAs) and other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs), and it emphasizes the recognition and protection of indigenous and traditional territories.

Signatories of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) committed and echoed with GBF to conserve the vital natural resources and maintain connectivity with each other. While doing so, each party (country) should formulate policies or legislation that will ultimately help safeguard the natural resources at stake. The CBD defines a protected area as “a geographically defined area which is designated or regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives”, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) describes a protected area as “a clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values”. IUCN World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), maintained by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), lists a total of 303,747 Protected Areas, which is 16.43% coverage of the land by protected areas and 9.61% of marine areas in the global context.

Signatories of the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) committed and echoed with GBF to conserve the vital natural resources and maintain connectivity with each other. While doing so, each party (country) should formulate policies or legislation that will ultimately help safeguard the natural resources at stake. The CBD defines a protected area as “a geographically defined area which is designated or regulated and managed to achieve specific conservation objectives”, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) describes a protected area as “a clearly defined geographical space, recognized, dedicated and managed, through legal or other effective means, to achieve the long-term conservation of nature with associated ecosystem services and cultural values”. IUCN World Database on Protected Areas (WDPA), maintained by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), lists a total of 303,747 Protected Areas, which is 16.43% coverage of the land by protected areas and 9.61% of marine areas in the global context.

Bangladesh aims to meet Global Biodiversity Framework Target 3. This ambitious goal requires increasing the country’s commitment through comprehensive, community-based efforts and financial mobilization. As a signatory to the CBD, Bangladesh has designated many areas as protected under the Wildlife (Protection and Safety) Act, 2012 (Act No. 30 of 2012). According to the act, “protected area” means all sanctuaries, national parks, community conservation areas, safari parks, eco-parks, botanical gardens, special biodiversity conservation areas, and national heritage and kunjaban declared by the Government.

Bangladesh aims to meet Global Biodiversity Framework Target 3. This ambitious goal requires increasing the country’s commitment through comprehensive, community-based efforts and financial mobilization. As a signatory to the CBD, Bangladesh has designated many areas as protected under the Wildlife (Protection and Safety) Act, 2012 (Act No. 30 of 2012). According to the act, “protected area” means all sanctuaries, national parks, community conservation areas, safari parks, eco-parks, botanical gardens, special biodiversity conservation areas, and national heritage and kunjaban declared by the Government.

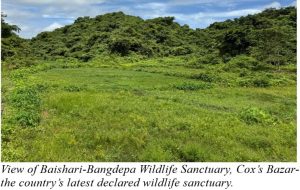

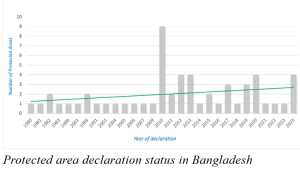

As of September 2025, Bangladesh has designated 57 Protected Areas, covering 818,313.886 hectares of terrestrial land and marine habitats, to conserve existing biodiversity. The terrestrial Protected Areas cover 470,213.886 hectares, which is 3.19% of the country’s total area. Forest department data showed that Himchari National Park of Cox’s Bazar was declared in 1980, and it is the country’s first protected area. Started in 1980, for the next three decades, the government declared only 16 protected areas. A significant milestone occurred in 2010, when nine new protected areas were declared in that year alone. Since then, 32 more areas have been declared as PAs. So far, two marine protected areas (Swatch of No Ground and Saint Martins) have been declared, which total about 8.8% of its Exclusive Economic Zone.

This year (2025) marks a significant achievement as the government has officially designated two ecologically important wetlands in the Rajshahi district as ‘Wetland-Dependent Wildlife Sanctuaries’. This initiative not only highlights the value of these ecosystems but also promotes the conservation of aquatic wildlife that depends on them. These wetlands serve as important wintering habitats for both native and migratory waders. There are many such productive and ecologically significant wetlands in the central and northeastern haor basin of the country, which can be brought under protection for food security and biodiversity conservation.

This year (2025) marks a significant achievement as the government has officially designated two ecologically important wetlands in the Rajshahi district as ‘Wetland-Dependent Wildlife Sanctuaries’. This initiative not only highlights the value of these ecosystems but also promotes the conservation of aquatic wildlife that depends on them. These wetlands serve as important wintering habitats for both native and migratory waders. There are many such productive and ecologically significant wetlands in the central and northeastern haor basin of the country, which can be brought under protection for food security and biodiversity conservation.

In Bangladesh, it is reported that about 5.6 per cent of the terrestrial area, along with the marine areas, has been designated as protected areas, at least in formal documentation. In reality, protected areas in Bangladesh are facing multifaceted threats, drivers such as encroachment of forest lands, fragmentation and deforestation, agricultural expansion, unplanned linear structures and road networks inside forests are a few to mention. A study carried out by Arannayk Foundation showed that about 1,618 kilometres (1,005 miles) of roads run through 38 natural forests in Bangladesh, including major motorways as wide as 15 meters (49 feet). Aside, 40 Km railroads have traversed at least six protected forests like Lawachara, Bhawal, Himchari, and Medhakachhapia national parks, and Fasiakhali and Chunati wildlife sanctuaries. Such road networks and rail tracks are responsible for countless animal roadkill incidents every day.

The government has piloted and implemented a co-management approach to conserve forests while providing sustainable benefits to the communities; however, the initiative does not seem to be working well.

Bangladesh is piloting an integrated approach that incorporates other effective area-based conservation measures (OECMs) alongside traditional protected areas to achieve this critical target. OECM is defined as “a geographically defined area other than a Protected Area, which is governed and managed in ways that achieve positive and sustained long-term outcomes for the in-situ conservation of biodiversity, with associated ecosystem functions and services and where applicable, cultural, socio-economic, and other locally relevant values” (CBD Decision 14/8). Globally, OECMs’ coverage is increasing day by day. According to the Global Planet Database, 6592 OECMs have been declared, of which 6373 are terrestrial and inland waters OECMs, and the remaining 219 are marine OECMs.

In Bangladesh, many privately owned natural habitats, state-owned areas, community conserved forests, or village common forests in Chittagong Hill Tracts, Tea gardens, and even some of the university campuses have immense potential to be included under the OECM concept.

To conclude, Bangladesh remains far from achieving the 2030 global goal, as its protected forests continue to face huge anthropogenic threats. However, integrating existing reserved forests, enforcing strict regulations, and integrating OECMs into the national system offer a way out to expand protected area coverage and strengthen conservation outcomes. The key take-home message is that effective conservation requires not only designation but also robust governance, strong commitment and active participation of all stakeholders involved.

Ashis Datta

Ashis Datta is an Assistant Professor of Zoology at Jahangirnagar University. Prior to joining academia, Ashis worked at the IUCN, International Union for Conservation of Nature, Bangladesh Country Office and Arannayk Foundation. He is an Erasmus Mundus M.Sc Scholar in Applied Ecology (Funded by the European Union) jointly conferred by the University of East Anglia, UK, the University of Kiel, Germany & University of Poitiers, France. He is doing research on wildlife ecology and conservation, including biodiversity inventory and survey, avian brood parasitism, movement ecology of animals in human-modified landscapes, wildlife in village common forests, and human-wildlife conflict mitigation.