Background

I wrote this account of history leading to the birth of Bangladesh at the request of the Editor of South Asian Review, an influential Quarterly published from London. At the time I was passing through London, en route to the US, as an envoy of Tajuddin Ahmed, the Prime Minister of Bangladesh Government in Exile, to initiate a campaign to stop aid to Pakistan. I wrote the piece from memory based on my first-hand involvements in the events and negotiations leading up to the military crackdown on the night of 25th March.

My objective was to put on record all that I had seen and learnt from his proximity to those historic events so it could be used as a source of information for both campaigners for Bangladesh and those who we were trying to influence in supporting Bangladesh. To the best of my knowledge, it was the first such written account of the background to the events of 25th March. More updated and comprehensive accounts of that period have appeared in later publications, including in the memoir of Dr. Kamal Hossain.

Prelude

The course of events within Pakistan, and Bangladesh in particular, is in great measure going to be determined by the intentions and decisions of those military leaders who rule Pakistan today. In assessing their possible course of action, it is instructive to look back on the events within Pakistan which culminated in the occurrences of March 25 and their elemental aftermath.

It was widely believed outside Pakistan that the decision by President Yahya to crack down on Sheikh Mujibur Rahman and his Awami League Party was due to a breakdown in their political negotiations in Dacca prior to March 25. This has been given some currency by President Yahya’s broadcast of March 26.1 But a subsequent press release of the Government of Pakistan dated May 6 stated that the military action was designed as a pre-emptive strike against a secession move by Mujib planned for March 26 and aided by a mutiny of Bengali troops and by Indian support.2 This subsequent explanation was at no stage touched upon by the President in his March 26 broadcast, and seems to have been a belated afterthought; no disinterested observer has come forward to lend credibility to this story.

What really happened? It is easy to piece together facts based on personal knowledge, but motives are harder to interpret. The emphasis will therefore be on putting the record straight, though some element of speculation remains unavoidable.

The First Round of Talks

The first round of talks on the constitution took place between President Yahya and Sheikh Mujib around the middle of January in Dacca. It was hoped that the President would at this stage spell out his own interpretation of the “unity and integrity of Pakistan”, and would indicate what aspects of the Awami League’s Six Point programme, if any, aroused misgivings within the ruling group. It was hoped that the “military interest” would be declared and that the terms on which the President was willing to transfer power would be put forward clearly.

The President’s Legal Framework Order (LFO), which was cited in parliamentary debates in Britain,3 was a remarkably unspecific document which could mean all things to all men. By suggesting that the President would not accept a constitution which prejudiced the unity and integrity of Pakistan it begged the whole issue of the election which was being fought, not on the existence of Pakistan, but on whose interpretation of the terms of nationhood had the widest acceptance. The LFO was relevant merely because it indicated that the President reserved the right to veto any constitution presented to him. Since his LFO was unspecific on what would invoke such a veto it was expected that he would spell out what seems to have been deliberately left unsaid in his LFO.

Contrary to all expectation, in these initial talks with Mujib, Yahya had no positive views to state. Along with his aide, Lieutenant-General Peerzada, he gave a careful hearing to the Awami League team on the implication of the Six Points. He seems to have been probing to see if the Awami League had done its homework, and found that the team was well briefed by its advisers on the legal and economic background. As he might have been aware, the Awami League advisers had in fact begun preparation a year before of a constitutional draft based on the Six Points and had worked out in detail the various negotiating options open to the party, and their implications.

At the end of this session the President appeared satisfied that the Six Points did not mean the disintegration of Pakistan, but suggested that agreement be reached with Mr. Bhutto so that an early transfer of power could take place. On his departure from Dacca, he referred to Mujib as the future prime minister of Pakistan.

The President Consults Mr. Bhutto

The Awami League believed that the reference to Mr. Bhutto implied that the President would elucidate his unarticulated views through Bhutto. From Dacca Yahya had gone to Bhutto’s home in Larkana, where they had had long talks; Bhutto’s impending visit to Dacca was seen as an occasion for serious discussion at which the real “West Pakistan interest” would be spelt out.

I had paid a visit to West Pakistan several weeks earlier to meet various PPP leaders who were involved in the task of drawing up the PPP version of the constitution. All were lawyers. Economists were conspicuously absent from the team. The talks were useful inasmuch as they presented a medley of PPP misgivings about the Six Points. But they confirmed that the PPP had done no homework on any alternative set of proposals, and that, in fact, different members of the team did not even have identical views on what aspect of the Six Points they objected to, and for what reasons. It was suggested that by the time the PPP team came to Dacca, for talks they would have an alternative draft which would form the basis of their own negotiating position.

Probing the Positions

Mr. Bhutto came to Dacca in the last week of January. He had direct sessions with Mujib, and then his “constitutional team” met their Awami League counterparts. As the talks proceeded, it became clear that the PPP had as yet not prepared their draft, and were merely probing the Six Points as Yahya had done before them. This made formal negotiation impossible, since negotiations imply alternative sets of positions and an attempt to bridge the gap between them.

The exploratory character of the talks and the need for a more substantive second round were blurred by Bhutto in his parting remarks to the press in Dacca on January 30. He said that there was no deadlock, and that “you cannot solve the problems of 23 years in three days”. He added that he planned to hold consultations in West Pakistan, and then continue his search for consensus and resume his negotiations and dialogue with the Awami League, and that for this reason the National Assembly session should not be held before the end of February. It was not, he said, necessary to attend the Assembly with an agreement already reached on different issues, because negotiations could continue even when the house was in session.

Mr. Bhutto’s Boycott

On January 31 at Dacca Airport, he said that the talks had been useful, and he was not unhopeful of compromise. He reiterated that the dialogue between the leaders should continue during the Assembly session, and referred to the parliamentary committee system as an established practice. It is, I think, misleading to infer from these remarks, as does M. B. Naqvi,4 that the fate of the talks was sealed in advance because of earlier acrimonious exchanges. The Awami League did not take Bhutto’s public postures that seriously. When, therefore, on February 15, following a meeting with Yahya three days before, Bhutto announced his boycott of the Assembly, the move was seen by the Awami League as bearing no relation to their earlier talks, but as part of a conspiracy with either Yahya or some of his generals to frustrate the democratic process.

The Attitude of the Generals

It was known that at least two generals, Major-General Umer, Chairman of the National Security Council, and Major-General Akbar, Chief of Inter-Services Intelligence, had serious misgivings about a return to democratic processes, particularly if Bengalis were to be in the ascendant. Whether Yahya or his aide Peerzada was merely the other side of a planned duet, or was put under pressure to line up with the “hawks”, is still being debated. Umer and Akbar had played a conspicuously partisan role, along with Mr. Rizvi, Chief of Central Intelligence, and Nawab Qizalbash, a Punjabi minister in Yahya’s cabinet, in support of Qayyum Khan’s Muslim League.

Once their objective of blocking both Mujib and Bhutto was foiled by the election results – which had been wrongly forecast by Akbar’s services to the very end – they switched support to Bhutto as West Pakistan’s rallying point against Mujib. Concrete evidence of their partisan role was provided by Ghaus Khan Bizenjo, a member of the National assembly from Baluchistan, Wali Khan, MNA from the North West Frontier Province and president of the National Awami Party, Mian Mumtaz Daultana, MNA from Punjab and president of council, Muslim League, and Sardar Shaukat Hayat, MNA from Punjab and president of the council of the Punjab Muslim League; they all reported visitations from Umer asking them to support Bhutto’s boycott of the Assembly. One of them said that Umer claimed to be acting in the name of President Yahya, who wanted a joint West Pakistani front against Mujib if in fact the boycott was to serve any purpose.

It is as yet unclear what objective was served by the boycott. Some suggest that the idea was to buy time to rally West Pakistani support behind Bhutto. In his round of talks with the Pathans Wali Khan claims to have told Bhutto that his party at least would back Mujib in the Assembly, and it is likely that a similar message was getting through to Bhutto from his other contacts with west wing leaders.

A two-thirds majority for Mujib’s constitutional draft was coming to seem more and more likely as anti-PPP parties bargained their support for a share in a coalition at the centre. The possibility of being excluded from central power threatened to split Bhutto’s own party, where a group of opportunistic landlords from Sind who had been taking a ride on his bandwagon said they would break ranks if power was denied them.

When Bhutto referred to the Assembly as a “slaughterhouse” he may well have articulated the fear of the generals who saw that if Yahya should be confronted with a constitution commanding enough support in the West to give it a two-thirds majority, it would be difficult to use his veto under the LFO. For this reason, time was needed to consolidate a joint front in the West behind Bhutto, who had now emerged as the spokesman of West Pakistani interests against Mujib.

But such a confrontation could only serve the purpose of frustrating the return to democracy, unless Mujib modified his Six Points. This was difficult, not only because Mujib had fought his entire campaign on this single issue, but also because neither Yahya nor Bhutto had as yet come up with a coherent and viable alternative. Had there been some intention to seek concessions from Mujib the discussions could have been used as a basis for serious bargaining with all cards on the table.

Instead, Bhutto was encouraged to provoke a public crisis which no Bengali leader could conceivably countenance without seriously compromising his position in the east wing. This implies that the very idea of a return to democracy had become repugnant to the hawks, that on February 15 Bhutto was merely taking the first step on the path which ended in the holocaust of March 25, and that everything in between was an elaborate charade.

Sheikh Mujib’s Responses

Yahya’s decision on March 1 to save Bhutto’s crumbling position in the West by postponing the Assembly session sine die brought to the surface the fear that had lain dormant in Bengal since the successful completion of the elections that the generals never really intended to transfer power.

Yahya’s decision on March 1 to save Bhutto’s crumbling position in the West by postponing the Assembly session sine die brought to the surface the fear that had lain dormant in Bengal since the successful completion of the elections that the generals never really intended to transfer power.

To postpone the Assembly was to postpone the prospect of Bengal’s assuming the share of power in the polity which they believed their 55 per cent share of population ought to give them: For people who felt that they had been denied their rightful role for 23 years through a series of plots and conspiracies hatched in the West, this was the last straw.

The public upsurge of support for Mujib’s call for non-cooperation had 23 years of accumulated emotion behind it, which explains its unprecedented dimensions. When the police and civil servants joined the judges in pledging support for Mujib a de facto transfer of power had taken place inside Bangladesh, and it had happened within a week of Yahya’s decision.

During the next three weeks Mujib’s house became in effect the secretariat of Bangladesh as Bengali secretaries, today still serving in Islamabad or Dacca, voluntarily offered their services to Mujib. Faced with such a vacuum, the Awami League was forced by events to move from non-cooperation to a selective exercise of administrative authority in order to prevent social anarchy and a breakdown of the economy.5 In this phase police officers subordinated themselves to Awami League volunteers. District commissioners cooperated with the Awami League sangram parishads (resistance committees) to administer the province.

Businessmen queued up to pledge their support to Mujib and seek solutions to their diverse problems. That this was not an urban phenomenon became plain when villagers cut the roads to the cantonment and besieged trucks attempting to ferry provisions to the Punjabi jawans. To any observer it was evident that short of a full-scale war of reconquest Yahya’s writ could never run again within Bangladesh. The widespread and indiscriminate killings by the army today reflect the experience of these 25 days, when it became evident that every Bengali was a potential enemy and that the loyalty of all traditional instruments of Islamabad’s rule was suspect.

Pressures on the Awami League

The force of public reaction appears to have taken Mujib as much as Yahya by surprise. Mujib realised that a mere return to the pre-March 1 position asking for the Assembly to be convened would be out of touch with the current mood. His demand for an end to Martial Law and a transfer of power to the people in the province merely gave expression to the reality on the ground. After two days of ineffective attempts to preserve Yahya’s authority the army had been withdrawn to barracks by Lieutenant-General Yakub, the Corps Commander and supreme authority in the province since March 1. Admiral Ahsan, the former governor, had asked to be relieved following the rejection of his plea against postponement of the Assembly session.

Yakub, who was no dove himself, had some kind of historical perspective; a scholar among generals, he had in three months mastered enough Bengali to discuss the writings of Bankim Chandra in the language. He saw that repression would not work. His reports were unheeded and he was replaced by Lieutenant General Tikka Khan, whose reputation as a man of action dated from his command of the Sialkot front in the 1965 war and during the Rann of Kutch operations. A “ranker”, he had also been involved in the pacification of a Baluch tribal uprising during Ayub’s days, and his appointment was seen as evidence of the triumph of the hard line. Yakub is since reported to have resigned his commission in protest, and the army is faced with the embarrassment of deciding whether to court martial one of its most distinguished generals.

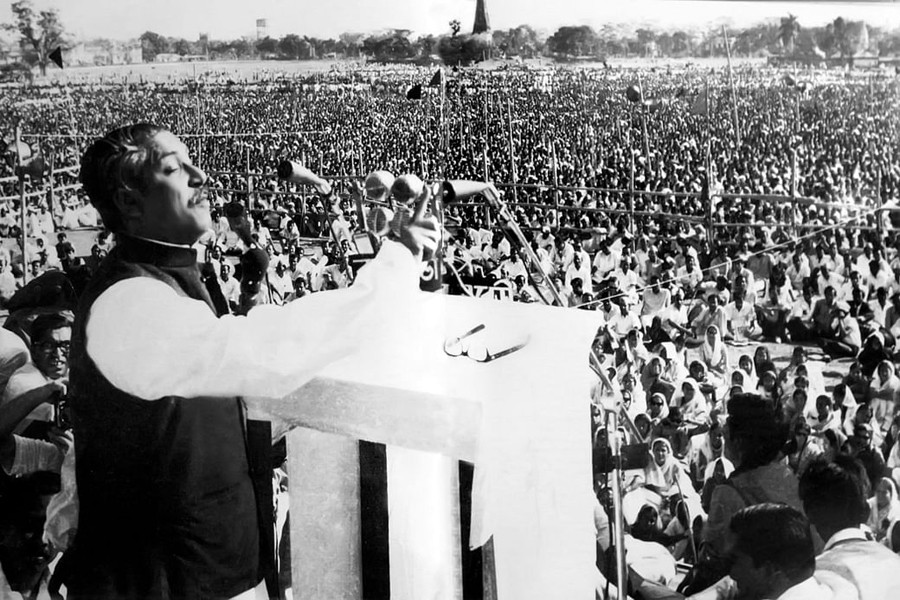

Yakub’s replacement was backed up by a continuous inflow of reinforcements for the garrisons. Yahya in a speech on March 6 had given further provocation by blaming Mujib for the crisis and not even alluding to Bhutto. His offer to reconvene the Assembly on March 25 was seen as belated and inadequate and as having been put in a context in which it was rendered virtually irrelevant. For this reason, it was believed by many that Mujib would use his public meeting of March 7 to proclaim independence, since Yahya had shown no willingness to come to terms with the consequences of his earlier decision. The army itself was put on full alert to go into action on March 7 in the event of such a declaration.

Mujib realised that any such proclamation would invoke massive carnage on Bengalis, and was reluctant to assume such a responsibility. His decision to persevere with non-cooperation while leaving the door open for a negotiated settlement within Pakistan was a compromise between the counter-pressures of the street and the army. There is no doubt that between March 1 and 7 he was under intense pressure to proclaim independence, and this became greater still after Yahya’s broadcast on March 6. But by the afternoon of March 7, he had successfully contained these pressures and committed his party to negotiations within the framework of Pakistan.

Subsequent suggestions that he lost control to extremist elements in his party bear no relation to the facts, and overlook the point that the crucial issue had been resolved before March 7, after which Mujib’s authority on all substantive issues was unchallenged within the party. When, for instance, student leaders decided unilaterally to impose a customs check on West Pakistanis leaving Dacca it took Mujib precisely four hours to get this withdrawn. It was largely the unchallenged nature of his authority which enabled him to use his volunteers to preserve law and order throughout the province during this period. Given the charged atmosphere, this was no mean achievement. It can be confirmed by a host of foreign journalists who had congregated in Dacca hoping to witness a major convulsion.

The President Comes to Negotiate

Denied the provocation of a UDI, or even the breakdown of law and order, Yahya seems to have opted for negotiations. He arrived in Dacca on March 15 with Generals Peerzada and Umer in his entourage. It has since been learnt that several other members of the junta had arrived less conspicuously and were staying out of sight in the cantonment.

Yahya began talks with Mujib within a day of his arrival. Mujib had tabled four demands, which were:

-

- Withdrawal of Martial Law.

- Transfer of power to the elected representatives.

- Withdrawal of troops to the cantonment and cessation of reinforcements.

- An inquiry into army firing on March 2 and 3.

Yahya conceded 4. The remaining three merely demanded judicial recognition of the de facto situation in Bangladesh. The troops were in barracks, power was with the elected representatives, and Martial Law orders were not being enforced.

Yahya in fact conceded all demands in principle at an early stage. It was the knowledge of Yahya’s concession which provoked Mr. Bhutto to demand a separate transfer of power in East and West Pakistan; and in so doing he articulated the concept of two nations by denying Mujib the right to speak for Pakistan. As the dominant force in the West, he insisted on a paramount position in that region. This was strongly opposed by the Pathans and Baluchis, who argued that since West Pakistan had ceased to exist as one unit Bhutto could speak only for Punjab and Sind.

Faced with these contrary demands, Mujib was confronted by the prospect of coalition at the centre. While a coalition was acceptable to him in principle, he was not willing to concede parity where his party held 167 seats to the PPP’s 87. Deadlock was avoided by consensus on the idea that power be transferred in the provinces to the majority party, with Yahya, in the interim phase, staying on in the centre. There was some suggestion that the parties nominate advisers to assist Yahya.

Legal Technicalities

On the question of lifting Martial Law, Justice Cornelius, who had been called in to advise on the legal aspects, first raised the suggestion that Martial Law must remain as the legal cover for the agreement or there would be a constitutional vacuum. This was seen by Mujib as mere legalism, and he pointed out to Cornelius that since Yahya and he had come to a prior political decision to withdraw Martial Law it was not for Cornelius to impose legal obstacles, but to provide the legal mechanism to give effect to the political decision.

The escape clause was in fact provided by Mr. A. K. Brohi, Pakistan’s leading lawyer, who had invited himself to Dacca and produced his own ex gratia solution to the problem after, presumably, discussing it with both parties. He suggested use of the precedent of the Indian Independence Act under which power was transferred by the Crown to the two sovereign states of India and Pakistan by an Act of Proclamation. This proclamation provided legal cover to all legislative acts until each state had framed its own constitution. Brohi argued that in the same way, Yahya could transfer power by proclamation and this would provide the cover till the Constituent Assembly had framed a constitution.

This point was accepted by Yahya and Cornelius, and it disappeared from the dialogues at an early stage. Since then, it has emerged that Daultana, of the Muslim League, and Mahmud Ali Qasuri, of the People’s Party, again raised the question of a legal vacuum and suggested that the Assembly would have to meet to give legal effect to the proclamation and assume sovereignty from Martial Law. When Daultana posed this to Mujib it was dismissed first because the issue had already been resolved and secondly because any move to put the proclamation to the Assembly would merely prolong Martial Law.

At a time when tension was mounting daily the time taken to assemble members and then debate the proclamation was seen as more than the nation could at that stage bear. It is thus surprising that Yahya used the issue of the legal cover as the final evidence of the mala fide nature of Mujib’s intentions, since his own team had already settled this matter and passed on to more substantive issues. The matter was obviously a mere piece of formalism, of relevance only to lawyers, and it was absurd to suggest that nations might break merely because of differences over a legal technicality.

Awami League Concessions

Mujib’s terms applied only to the interim phase between the lifting of Martial Law and the passing of the new constitution by the Assembly. It was not certain how long this phase would last, but there was no question but that the long-term basis for nationhood must be decided by parliament, who would assume sovereignty through the instruments provided by the constitution. At that stage it was generally agreed by both parties that the Six Points would at least have to provide the basis for this document.

Yahya had argued that while the Six-Points had been worked out for defining Bengal’s relation to the centre, its application to the West wing provinces would create more difficulties. This had always been conceded by the Awami League, whose Six Points were based on the existence, because of the peculiarities of the country’s geography, of two economies within one polity. Yahya’s demand for a separate deal for the West was readily conceded by Mujib, since he himself had no power base of his own to defend, having failed to win a single seat there.

Yahya suggested that West Pakistan might need more time to work out inter-provincial relations in the West in a post-One Unit region, since no work had been done on this by any of the parties there. He suggested separate sessions of the Assembly for either wing so that this task in the West could be done without any interference by the East wing.

The whole proposal was designed to accommodate Bhutto, who was obsessed by the fear that Mujib would enter into collusion with the smaller parties and regions to neutralise him. He wanted a free hand in the West, and Yahya secured this for him from Mujib. But in accepting the proposal Mujib alienated his potential support in the West, which had increased considerably following Bhutto’s boycott decision, and as a result, when Yahya initiated his military operations, Mujib found himself friendless in the West.

To suggest that the idea of two assemblies was basically Mujib’s was to do violence to logic, since the Awami League not only had a clear majority of its own, but by then could command more than two-thirds of the votes in the house behind any position it chose to take.

From Politics to Economics

Once the format for the political and legal basis for the transfer of power had been determined, there remained the more substantive question of the distribution of powers between the province and the centre in the interim phase. It was agreed by both parties as a guiding principle that the basis should not deviate too much from the final version of the constitution which was expected to be based on the Six Points. Since economics was the key issue here, M. M. Ahmed, Chief Economic Adviser to the President, was brought in.

The Awami League team again argued that at least the de facto situation must be recognised. By then export earnings and revenue collections were being paid to a Bangladesh account. M. M. Ahmed found no difficulty in conceding that these powers be formalised. He also conceded to the province the right to make its own trade policy and to have its own reserve bank to determine monetary policy for the region. As an amendment, delivered to the Awami League team at their last meeting on March 23, he proposed:

-

- that since it would take time for the charters and the new reserve banks to emerge, the State Bank at Dacca assume this role for Bangla Desh; in case of conflict in regional monetary policies the State Bank of Pakistan would have powers to intervene;

- that for financing the centre in revenue and foreign exchange existing arrangements continue;

- that for foreign aid a joint delegation go to the consortium; it could by agreement be dominated by Bengalis and could be divided on a prearranged formula; once aid had been pledged at the consortium the provinces could negotiate individual agreements on their own.

These represent the sense of his proposals. His amendments were worded loosely, and in discussing them the Awami League advisers tightened up the wording to lend them clarity; otherwise, his amendments were accepted. There was nothing to prevent the formulation of a joint draft of the proclamation for transferring power any time from March 25 onwards.

It is worth noting that in the interim phase all inter-provincial matters for the west wing were to rest with the centre, as had been provided for once the One Unit had been dissolved. This as well as other proposals were intended only for the interim phase. Once the West worked out their problems in separate sittings, the two houses would come together for a joint session to frame the constitution.

The Negotiations Halted

It is evident then that there was no breakdown in the negotiations, and in fact agreement on all substantive points had been reached. M. M. Ahmed claims that this was his view and that accordingly he left for Karachi on March 25. The Awami League now sees his departure as evidence that the army were at that point bent on action, since Ahmed was a key negotiator who should at least have stayed to see the response to his own proposals.

In fact, the sessions of March 23 were the last to be held, and all calls to Peerzada for the holding of the final session went unanswered. Yahya had still not put any firm proposal of his own on the table, or even stated what his final terms were for a settlement. As always, the debate took place on the Awami League draft of the interim constitution, and they were as before left with their cards exposed while the world remained ignorant of the real intentions of the President and his junta.

Bhutto had arrived in Dacca with his own team, and was having separate sessions with the President’s team. This was because the Awami League felt that any substantive settlement lies in Yahya’s hands, and Bhutto’s role, to judge by past experience, was derivative. Since the President had so ably carried Bhutto’s brief no fear was felt that Bhutto would in fact oppose the settlement.

As it happened, while the two teams were in session in President’s House, Dacca, Yahya himself was in the Dacca cantonment talking to his generals. During this time the army had escalated the situation in Chittagong by suddenly deciding to unload a munitions ship which had been immobilised for 17 days by the non-cooperation movement.

At 11 p.m. on March 25 troop movements into Dacca began. Yahya had flown off to Karachi a few hours earlier. Negotiations had been overtaken by war.

Endnotes

-

- See Dawn, 27 March 1971.

- See Dawn, 7 May 1971.

- See speech by Sir Frederic Bennett, Hansard, 14 May 1971.

- See Naqvi, M. B., “West Pakistan’s Struggle for Power”, South Asian Review, Volume 4, Number 3, April, 1971.

- See Forum, 13 and 20 March 1971, for an account of this process.

This paper was published in South Asian Review, London (July 1971)

Rehman Sobhan

Rehman Sobhan is a noted Bangladeshi economist and freedom fighter who played an active role in the Bangali national movement. He is the Founder Chairman, Centre for Policy Dialogue, Dhaka, Bangladesh. He was one of the several economists whose ideas influenced the 6-point programme of Sheikh Mujibur Rahman. He served the first Government of Bangladesh as Envoy Extraordinaire with special responsibility for Economic Affairs, during the Liberation War in 1971. He was a member of the first Bangladesh Planning Commission, and in the 1980s headed the premier development research facility, Bangladesh Institute of Development Studies (BIDS). In 1990–91, he became a Member of the Advisory Council of the President of Bangladesh in charge of the Ministry of Planning and the Economic Relations Division. In 1993, he founded the Centre for Policy Dialogue (CPD), one of Bangladesh’s most prestigious think tanks. He also headed the South Asia Centre for Policy Studies (SACEPS) from 2000 to 2005, one of the leading think tanks for promoting regional cooperation in South Asia. A former Professor of Economics at Dhaka University, he has authored numerous books and articles on various developmental issues.