Chars: Stories of life and resilience

In Bangladesh, chars or mid-channel islands are an important part of the landscape and ecology, and our history and heritage. Indeed, this delta country is largely made of alluvial soil deposited by the three main river systems – the Ganges/Padma, the Brahmaputra-Jamuna, and the Meghna Rivers. Upward an estimated 20 million people live in chars in the floodplain of the major river systems and in the coastal regions. The char dwellers are by and large poor, isolated and highly vulnerable, both physically and socially, without land rights and sustained sources of living. They mostly live as tenants/users and are periodically forced out to migrate due to erosion. The chars are also pockets of extreme poverty in the country.

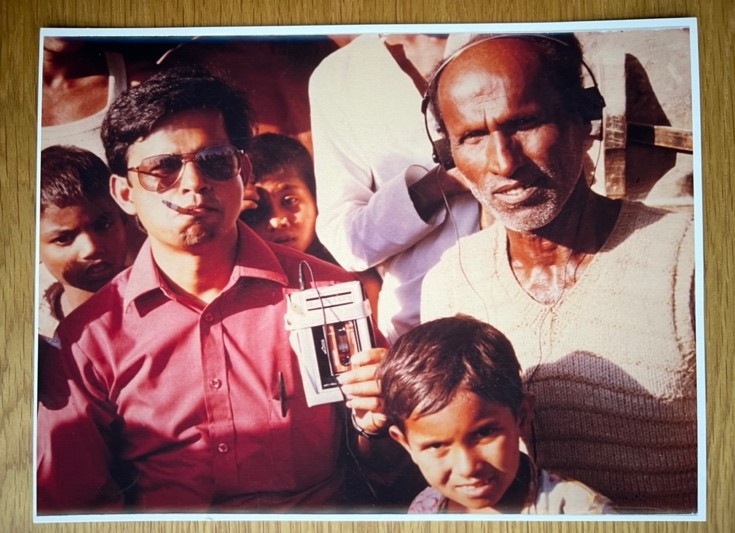

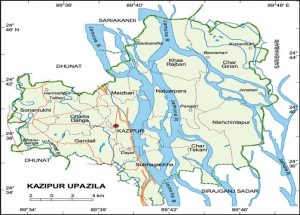

I have lived and worked in Kazipur-Serajganj chars on the Jamuna River for my research and later for consulting work. In 1984/85, I carried out an ethnographic study on flood and erosion disasters and displacement for my doctoral programme at the University of Manitoba, Canada. For many years, my core research has been on char settlement, their economies and social organizations and how these have been historically shaped by the colonial and post-colonial land tenure and administration with regard to alluvial and diluvial lands.

I have many stories about chars and char life in Bangladesh. The stories are based on my experience as an author, fieldworker, consultant and a public scholar. In this short piece, I look back at Kazipur both as a researcher and a consultant. I discuss briefly the range of my project work and engagements, including a critique of the current approaches to river management in Bangladesh in favour of a more sustainable and adaptive approach. To my knowledge, not many anthropologists or consultants have reported on their project experiences in the form of stories and personal reflections in such an integrated fashion.

Looking back, ahead and beyond

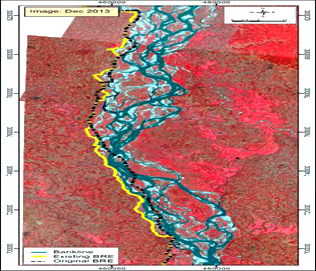

In June 2014, I returned to Kazipur after some 30 years as a World Bank consultant on the River Bank Improvement Project (RBIP). The project involved bankline protection work, reconstruction and/or retirement of the Brahmaputra Rightbank Embankment (BRE), built in the mid-1960s for flood protection. At that time, the embankment was located approximately 1.5 km inland from the bankline of the Brahmaputra-Jamuna River. Since then, the embankment had to be retired in selected sections due to periodic bankline erosion. Only 61 km of the original 180 km of the BRE remained; the rest was retired and/or degraded beyond repair, and still facing the risk of erosion due to continuous westward migration of the Brahmaputra-Jamuna River. The endemic erosion causes loss of land, settlements, infrastructure and other assets, leaving hundreds of thousands of people destitute every year. Those displaced by river-erosions are often categorized as internally displaced persons (IDPs) in the country. Between 2008 and 2014, as per estimates by the Internal Displacement Monitoring Centre, close to five million people were displaced by river erosion and other forms of natural disasters in Bangladesh.

I lived in Kazipur for 15 months (May 1984-August 1985), conducting fieldwork for my dissertation work. The primary focus was on Char Chashi, a riparian village in the middle of the Brahmaputra-Jamuna River, although several other char and mainland villages were part of my study area. Erosion and displacement were recurrent phenomena in the area. Indeed, in the mid-1980s, Kazipur along with Chilmari in the north and Bhola in the south were identified as areas most vulnerable to erosion in the country. In Kazipur, every household living in the char villages reported displacement at least once in their life time. Many reported multiple displacements. However, despite repeated displacements, there was very limited out migration; over 90% of the displaced remained generally within the locality and self-resettled in nearby villages and/or chars with kin and community support with the hope that their eroded lands would re-appear over the years. This typically happens as a dynamic process of erosion and accretion in the floodplain. A large number of those displaced, often from the same village, were found to rebuild new communities on the BRE embankment with mutual aid and community support. This informal and community-assisted resettlement is a local adaptative response to riverine displacements in the floodplain.

My Kazipur work was one of the early detailed anthropological baseline studies on the floodplain ecology and settlement, and remains to date a key reference source for social-

anthropological research on flood and erosion disasters in Bangladesh. My trip back to Kazipur offered me the unique opportunity of dealing with flood and erosion issues from a development perspective that included not only mitigation of project impacts, but also the designing of social development programmes for project-affected people and communities in the area. Indeed, it was expected that the much-needed bankline protection work and infrastructure development work under RBIP would not only bring stability and renewed confidence for investments in the region, but also promote access to local and national markets and thus have great potential to breaking the cycle of poverty in the floodplain region.

For project preparatory work, I travelled extensively up and down the BRE alignment and held meetings with bankline communities in Kazipur and Sariakandi, including trips to char villages across the channels. I met with many villagers from Char Chashi, the char village I studied in 1984-85. By 2014, the Jamuna River had washed away nearly one-third of the area of Kazipur upazila (sub-district). I was also told that the Char Chashi villagers had moved between three and five times over the last 30 years, and were now scattered throughout different chars due to repeated erosion and migration. I was thrilled to meet ‘my people’ after a very long time. Jahangir Chaklader, a villager from the char I studied and now a resident of mainland Kazipur, was our guide. I realized the geography and social characteristics of the char areas had changed significantly. The economy had diversified and many young women from the char areas found employment in readymade garment industries in Dhaka.

My trip back to Kazipur represented a full circle journey in my research and consultancy work. I was heading a large team of local and international consultants dealing with project impact assessments relating to livelihood, gender, public health, and stakeholder consultation for community input to minimize negative project impacts; designing of compensation packages; and determination of choices and options for resettlement and social development programs. People in Kazipur were extremely happy to see me as a member of the project team.

I recalled fond memories from my field work days in 1984-85, and was stunned to find that the place in Kazipur where we lived was completely washed away despite the protective works. Instead, I saw a huge sand bar, not yet ready for cultivation, or any other use. The embankment where hundreds of families had once lived was retired several times over the past 30 years, following continuous changes in the river course, particularly during high floods every other year.

I held a series of meetings with local villagers along the bankline and with local upazila administration to assess the current situation and determine how best to conduct the project impact assessment over the next several months. During one of the meetings at the community level,

I was moved by the statement of an elderly villager that I was considered a ‘son’ of Kazipur, and therefore, the people of Kazipur would provide all necessary support to the project planning team. We carefully organized the field project, conducted social surveys and stakeholder meetings to identify impacts of the ongoing erosion in order to design comprehensive compensation and resettlement packages. The field project team included some local youths and NGO workers, who were to complete the census and social surveys, including gender and livelihood surveys under the proposed project

River management and development

Measures for river management in the country dates back to the United Nations Krug Mission of 1956, following the massive floods in East Pakistan (now Bangladesh) in 1954. The Krug Mission Report stressed the need for the construction of high embankments to confine the waters of major rivers within their main channels and to cordon off large areas from flooding. Many experts are of the opinion that the Krug Mission set off the process of water development in the country in the wrong direction. Little attention was paid by the Krug Mission Report to the environmental and ecological aspects and to the local cultural and indigenous practices related to flood, land use, land rights, and socioeconomic processes in the river delta. Further, floods are intricately linked to the very survival of the people in this delta country due to its dependence on rice and fish as the main staple that need tremendous amounts of flood water to grow and flourish. Indeed, Bengalis are widely known for their love of rice and fish (machhe bhate Bangali) over all other food. So, it is neither possible nor desirable to completely eliminate flooding.

The Bangladesh Water Development Board (BWDB) over many years has built many physical structures for flood control and bank protection in the Jamuna and other river systems. However, we often see failure of erosion protection work. Indeed, there is a long history of failure of spurs, groins and revetment works in the Jamuna system. The short-lived and limited utility of some of the physical infrastructures built so far have led to widespread doubts about the wisdom of this approach. We should look beyond this engineering solution to a more holistic approach in managing flood and erosion in this country. The Bangladesh Delta Plan 2100 (BDP2100) seems to have traction on this integrated and adaptive approach to river management. Adopted in 2018, the BDP2100 focuses on a long-term integrated ‘vision,’ offering both technical and sustainable social and environmental solutions dealing with complex issues and risks related to flooding, displacement, and migration from a holistic perspective.

Concerns over Jamuna River stabilization

The Jamuna has a long history of bankline erosion. The river is highly braided, morphologically very dynamic and serves as an important navigational route of the country. Due to its immense size and the braided nature of the multi-channel Jamuna River and other major rivers (e.g., Padma/Ganges and Meghna), the BWDB, following the Delta Plan 2100, has put a high emphasis on gradually stabilizing the main rivers for better river management, reduce disaster risks, and boost economic growth. BWDB appears to have taken a move in favour of narrowing the multi-channel Jamuna River into a single or double-channel plan form, combined with dredging for navigational channel, and protection of the existing bankline against future bankline erosions. The pilot project, funded by the World Bank, is titled Jamuna River Sustainable Management Project- I. Subsequent projects will likely invest huge sums (in the order of billions of dollars) over the next decades.

The move for char stabilization has raised concerns regarding the long-term hydro-social impacts, if implemented without a careful consideration of the transboundary nature of the river systems, with Bangladesh located at the lower reaches, with serious threats to the rich local biodiversity in the country. Secondly, Jamuna not only carries water but also massive amounts of sediment, which, in the process of stabilization, may pose a huge challenge with regard to sediment management. Third, there is nothing innovative in the design of the pilot structure. The BWDB has been doing such structures in the Jamuna River for decades. Fourth, there may be need for some limited protection work, but any attempt to reducing the width must be based on a master plan with traditional engineering model, and should be done step-by-step by observing the responses of the river, including a thorough review of the country’s alluvial and diluvial land laws to protect the rights of char dwellers and land owners in the floodplain.

Living with the river

The experience to date has shown us that the mighty Jamuna River and the sheer magnitude of the monsoon floods preclude almost all types of engineering works as a means of controlling flood and erosion processes. As noted earlier, many infrastructures along the Jamuna River have been either short-lived or of limited utility. Since there appears no practical means of stopping erosion despite existing embankments and protective works, the solution lies in developing socio-economic measures – for instance, improving preparedness for loss reduction, recovery, resettlement, formulation of new laws for charland use and ownership, new livelihood programs, etc. to mitigate the impact of erosion events, rather than preventing erosion itself. In other words, it may be wiser to live with the river than to fight against it. Accordingly, we need to identify and strengthen the localized strategies of resilience and adaptive mechanisms for protecting the floodplain users themselves, their crops and the livestock.

The ‘living with the river’ approach in no way romanticizes the traditional or ‘local coping’ as the only or the best approach. The local coping should be considered the starting point to build up resilience and capacity to adapt to erosion disasters and displacement. Of course, some intervention and limited protection work for major towns, ports and other important establishments will always be necessary, along with some form of stabilization work in selected sections of the Jamuna and other rivers. However, a full-scale programme for stabilization of the major rivers may be unnecessary, affecting human populations and their agricultural needs, apart from impacting the essential ecological processes and the biological diversity thereof. It is possible to plan such alternatives and adaptive pathways to manage the rivers, which are in line with the Delta Plan 2100. A balanced approach is necessary that takes into consideration the interconnections between adaptive measures and technological fixes for river management. There is a greater need for understanding the rivers before we fundamentally transform them. Unfortunately, this perhaps is not happening in Bangladesh now!

Mohammad Zaman

Dr. Mohammad Zaman is an internationally known development/ resettlement specialist. He has worked in many major projects for the World Bank in Bangladesh and in other countries in Asia and Africa. Dr. Zaman’s most recent edited book (co-editor Mustafa Alam) is titled Living on the Edge: Char Dwellers in Bangladesh, Springer, 2021. E-mail: mqzaman.bc@gmail.com

Very insightful article. Many thanks Dr. Zaman for sharing your experiences and knowledge! I hope our paths will cross one day soon.